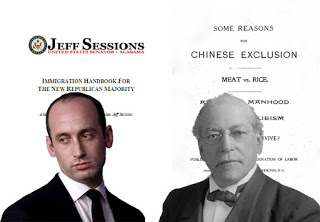

Stephen Miller, architect of the Trump administration's immigration policy is getting a lot of bad press these days. Some wags (and even relatives?) juxtapose Miller's photo to one of Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels, insinuating likeness of facial expression is a predictor of ideological leaning and propaganda technique. The comparison is as unhelpful as it is unfair. A more apt comparison would be with Samuel Gompers, founding president of the American Federation of Labor. Miller doesn't look at all like Gompers but his rhetoric echoes Gompers's Chinese exclusion advocacy at the dawn of the twentieth century. It is only by discerning the similarities and differences between Miller's position and Gompers's that an effective rebuttal to Miller's policy prescriptions can be mounted.

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

Miller doesn't look at all like Gompers but his rhetoric echoes Gompers's Chinese exclusion advocacy at the dawn of the twentieth century. It is only by discerning the similarities and differences between Miller's position and Gompers's that an effective rebuttal to Miller's policy prescriptions can be mounted.

Miller's 2015 anti-immigration manifesto, Immigration Handbook for the New Republican Majority, is an articulate, compelling strategy polemic. It also discretely avoided any overt expression of racism or white supremacism. The handbook stresses polling that concluded "an economically focused message [on immigration] resonates with voters of all economic backgrounds and all ethnic backgrounds." More specifically, it cites the result that "86% of black voters and 71% of Hispanic voters said companies should raise wages and improve working conditions instead of increasing immigration."

For those without either the time or stomach to wade through Mr. Miller's analysis and polemic, here is a synoptic collection of excerpts:

Simply put, we have more jobseekers than jobs.

The principal economic dilemma of our time is the very large number of people who either are not working at all, or not earning a wage great enough to be financially independent. The surplus of available labor is compounded by the loss of manufacturing jobs due to global competition and reduced demand for workers due to automation.

We have an obligation to those we lawfully admit not to admit such a large number that their own wages and job prospects are diminished. A sound immigration policy must serve the needs of those already living here.

So whether comprehensive, piecemeal, step-by-step, incremental, or whatever other process one conceives, the question that must be asked is this: will the legislation make life easier or harder for American workers?

Is there a single more reasonable proposition than to say that a nation’s immigration policy should consider first what is good for its own citizens?

Republicans—who stood alone in Congress to save America from the President’s [Obama's] immigration bill and who alone have fought against his executive amnesty—must define themselves as the party of the American worker, the party of higher wages, and the one party that defends the American people from Democrats’ extreme agenda of open borders and economic stagnation.

No issue more exposes the Democrats’ colossal hypocrisy than their support for an immigration agenda pushed by the world’s most powerful interest groups and businesses that clearly results in fewer jobs and lower wages for Americans.

Paragon polled three sentences lawmakers should use that have been too absent in the immigration conversation:I especially like the part about Republicans defining themselves "as the party of the American worker, the party of higher wages." That is not to say they would have to be the party of workers and higher wages. But who could argue with that polling sentence about what the first goal of immigration policy needs to be?

- The American people are right to be concerned about their jobs and wages, and elected officials should put the needs of American workers first.

- The first goal of immigration policy needs to be getting unemployed Americans back to work—not importing more low-wage workers to replace them.

- Immigration policy needs to serve the interests of the nation as a whole, not a few billionaire CEOs and immigration activists lobbying for open borders.

Contrast Miller's arguments with the position offered by M/I.T. professor and former director of research for the I.M.F., Simon Johnson in a 2014 Guardian feature on the U.S. jobs crisis:

To reduce the persistently high unemployment rate in the United States, Congress should move to relax some of our current constraints on immigration.

This is a controversial idea because many people are under the impression that allowing in more immigrants would push up unemployment. But that would only be the case if the number of jobs in the US were an unchanging constant.

In fact, some categories of immigrants tend to create jobs, so letting them in would directly increase employment opportunities for people already in the United States.Whose argument sounds more compelling? Miller's or Johnson's? For me, it's a no-brainer. They are both right and they are both wrong. Allowing in more immigrants doesn't necessarily push up unemployment. Nor does it necessarily create more jobs for people already in the United States, a claim that Johnson deftly sidesteps actually making by referring to some categories of immigrants.

Johnson's position represents the conventional wisdom among economists. In fact, as I mentioned in an earlier post, the same argument was reiterated in a direct response to Miller's manifesto by Walter Ewing of th American Immigration Council:

Employment is not a "zero sum" game in which workers compete for some fixed number of jobs. Immigrant workers spend their wages in U.S. businesses—buying food, clothes, appliances, cars, etc. Businesses respond to the presence of these new workers and consumers by investing in new restaurants, stores, and production facilities. And immigrants themselves are 30 percent more likely than the native-born to start their own business. The end result is more jobs for more workers. The economic contributions of unauthorized immigrants in particular would be amplified were they given a way to earn legal status.Yes, employment is not a "zero sum." But no, labor supply does not "create its own demand." More importantly, however, simply repeating that platitude will not persuade underemployed or underpaid workers that immigration has made things better for them. The danger is that people who find Johnson's and Ewing's arguments unpersuasive will encounter no alternative to Miller's.

That is where Samuel Gompers parallel comes in. This is not to say that his advocacy of Chinese exclusion was correct or justified. But it was paired with a positive proposal for fighting unemployment and raising wages. That proposal can be summarized in a phrase Gompers cited in 1887, "That so long as there is one man who seeks employment and cannot obtain it, the hours of labor are too long."

Contrary to the claims of many mainstream economists, the job creating dynamic of shorter hours is not based on the assumption of "a fixed amount of work" that can be divided up in different ways to create fewer or more jobs. The shorter hours policy advocated by the American Federation of Labor in the 19th century was based on a dynamic theory of leisure, consumption and technological improvement that in many respects anticipated Keynes analysis more than fifty years later. Dorothy Douglas wrote about Ira Steward's Eight-Hour Theory in the 1930s and evaluated it positively.

By contrast, Miller's immigration manifesto offers no positive program for job creation. It is simply supposed that the jobs currently occupied by immigrants would have existed anyway and would have been filled by American-born workers had there been less immigration. This is an unjustified supposition. It is conceivable that without the immigration that has occurred there would have been even less new employment created for American-born workers.

The real danger of the Miller policy prescription is yet to come. Halting immigration will not create jobs. When the policy fails -- as it inevitably will -- it will become incumbent on the Republican administration to escalate the policy by driving out previously admitted, legal immigrants.