This video lecture focuses on the current crisis of Economics and the relevance of Political Economy as a realistic and credible alternative. The last global capitalist crisis of 2008 reopened discussions on the issue of economic crisis; an issue long forgotten by the dominant tradition within economic theory, Economics. Economics (that is the study of the economy in abstraction from social and political relations, as a ‘play’ between individuals and not between social classes) has failed, in both its Neoclassical and Keynesian versions to forecast, comprehend and confront the 2008 crisis. This is a repetition of Economics’ dismal record against almost all previous major economic crises. Its Neoclassical version considers capitalism a perfect system where crises erupt only because of

Topics:

Stavros Mavroudeas considers the following as important: Video από συνέδρια. τηλεοπτικές εκπομπές κλπ.- Videos from conferences, lectures, tv etc., Ομιλίες & Διαλέξεις - Speeches & Lectures, Χρήσιμο διδακτικό υλικό - Useful teaching material

This could be interesting, too:

Stavros Mavroudeas writes Financialisation versus Marxism – S.Mavroudeas (video and supporting material)

Stavros Mavroudeas writes Ημερίδα για τον Λένιν – 12 Οκτωβρίου 2024, Πάντειο Πανεπιστήμιο

Stavros Mavroudeas writes «Πολιτική και οικονομία στη δημοκρατία» – Στ.Μαυρουδέας, podcasts του ΕΚΚΕ

Stavros Mavroudeas writes “Κοινωνική Ασφάλιση – Συνταξιοδοτικό & Αμοιβές της εργασίας στο Δημόσιο” – Ρέθυμνο 11/3/2024

This video lecture focuses on the current crisis of Economics and the relevance of Political Economy as a realistic and credible alternative. The last global capitalist crisis of 2008 reopened discussions on the issue of economic crisis; an issue long forgotten by the dominant tradition within economic theory, Economics. Economics (that is the study of the economy in abstraction from social and political relations, as a ‘play’ between individuals and not between social classes) has failed, in both its Neoclassical and Keynesian versions to forecast, comprehend and confront the 2008 crisis. This is a repetition of Economics’ dismal record against almost all previous major economic crises. Its Neoclassical version considers capitalism a perfect system where crises erupt only because of deformations of the ‘normal’ functioning of the market. Its Keynesian version maintains that capitalism – because of its anarchic nature – is prone to crises but the existence of an overseer (in the form of the state) can secure the avoidance of such sad episodes. Both versions have failed utterly as the crisis hit both deregulated and regulated economies. On the other hand, Political Economy – the other major tradition in economy theory – proposes a more realistic and credible understanding of the economy. The latter is not an ‘play’ between individuals but between antagonistic social classes. This class struggle within the economy has an inherent social nature and is necessarily linked with politics. Thus, Political Economy argues for a unified analysis of the economy, the society and politics. Within Political Economy the Marxist tradition argues that capitalism is a system that passes from periods of booms to periods of bust. This is the normal functioning of the system as it exhibits cyclical fluctuations (economic cycles). Thus, crises are not an aberration but a normal characteristic. Moreover, state intervention can affect the eruption and the evolution of crises but it cannot extinguish their existence. This analytical framework has greater explanatory power that Economics.

The notes of the lecture follow:

‘Economic Crisis and the crisis of Economics: Political Economy as a realistic and credible alternative’

Stavros Mavroudeas

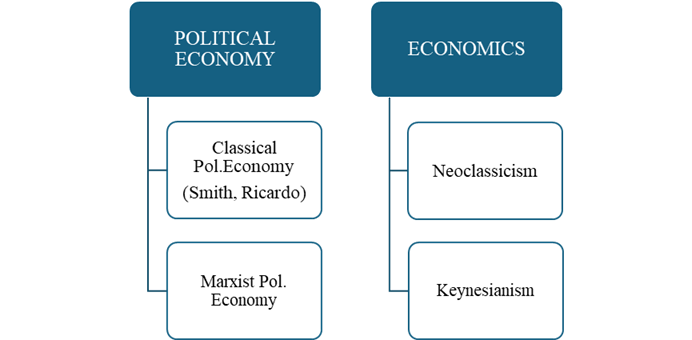

The subject of this video lecture is the current crisis of economic theory, of economics, and the relevance of political economy as a reliable and credible alternative to the former. Now let me specify a few concepts in order to be more precise. Historically, economic thought is divided between 2 main different alternative approaches on how to understand and comprehend the economy. The one is political economy and the other, is economics. Table 1 summarizes the main differences between these two approaches.

Table 1: Main alternative economic approaches

| POLITICAL ECONOMY | ECONOMICS | |

| Agents | social classes the economy is a social ‘game’ | individuals the economy is a ‘game’ between individuals |

| Primary focus | production | circulation (and only that involved in market exchange |

| Analytical framework | Dual system: (labour) values detn. prices | Single system: prices detn. prices |

| Analysis of the economy in relation to society and politics | in a unified framework | separately |

Let me elucidate a bit on these differences.

Difference number 1. Political economy considers the economy as a social ‘game’, as a ‘play’ between social classes, whereas Economics consider the economy as a ‘play’, a ‘game’ between individuals. To put it in simpler terms, Political Economy has a social understanding of the economy, whereas Economics have an individualistic non-social understanding of the economy. A corollary of these main differences is that for Political Economy the main agents of the economy are social classes, whereas the main agents for Economics are individuals.

Economics consider individuals as very different one from another, so they cannot be grouped in sets, in social groups and classes. On the other hand, of course – and this is a well-known major problem for Economics – all these completely different individuals obey the same behavioral rule. That is, the max-min criterion: in every economic act they maximize utility and minimize costs. This is a very strange position: agents that are very totally different one from another, but all of them following the same behavior. It is like having a myriad of men with totally different body types but all of them wear the same size and type of clothes. In contrast, Political Economy argues realistically that members of different classes have different patterns of socio-economic behaviour. Hence, they reject the behavioural uniformity of Economics.

Difference number 2. Political Economy in its analysis of the economy focuses on production (the so-called real economy). The sphere of production is considered rightfully as the crucial (dominant) sphere of the economic circuit. The other spheres of the economic circuit (circulation, distribution) follow from production. On the contrary, Economics focuses on the sphere of circulation; and a special case of it, commodity exchange. To put it simply, for Economics the economy is simply the market. For this reason, they have a marked difficulty comprehending any economic activity that is not commodified. Now, we know that restricting the economy basically to markets is erroneous. The economy is many other things, apart from markets. This myopia explains Economics’ inability to grasp other socio-economic systems except capitalism; and they tend to collapse all other to capitalism.

Difference number 3. Political Economy analyzes the functioning of a socio-economic economy in which there is a market through a dual system. In a nutshell, it argues that market prices are not self-determined (through the volatile interplay between supply and demand in circulation) but are determined by the more stable labour values (the labour expended in production in order to produce the commodities that subsequently acquire prices). Hence, the ‘fundamentals’ of the sphere of production (labour values) determine the prices (the interplay between supply and demand in the sphere of circulation). Economics, on the other hand, have a single system: there are only prices. It considers only circulation, so they practically argue that prices determine prices.

Difference number 4. Political Economy argues that the analysis of the economy must be conducted in a unified framework with the analysis of political and social relations. In contrast, Economics maintain that economic relations should be analysed independently from social and political relations. For them, in the economy there are only individuals. In social and political relations there are grouping (not necessarily classes but preferably short-lived inter-class pressure groups etc.).

Of course, there are subdivisions within these two main camps. Table number 2 delineates, these subdivisions.

Table 2: Sub-divisions of the Main alternative economic approaches

To put it simply, Political Economy is subdivided in Classical Political Economy and Marxist Political Economy. The first is the tradition stemming from Adam Smith and David Ricardo. And the second stream, stems from the work of Karl Marx.

Economics, are subdivided in two main traditions. The first one is Neoclassicism (supply side Economics) and the second is Keynesianism (demand side Economics).

Since the end of the 19th century, Economics have become the dominant approach in theorizing, and analyzing the economy and informing economic policy. To put it simply, in capitalist societies Economics dominate the governmental and academic decision centres. Thus, they constitute the Orthodoxy or the Mainstream. Political Economy continues existing (mainly in the forms of Marxist and Radical Political Economy) but it is relegated to the ‘underworld’, excluded from the commanding heights of economic policy making.

However, because of their a-social nature and unrealistic fundamental assumptions (perfect markets etc.), Economics has been scarred by internal problems and strife. These problems, I will argue, stem from their belief that you can analyze the economy as an individualist game and not as a social game. This deficiency creates serious problems that, unsurprisingly, emerge particularly during crisis. That is during periods that the economy behaves abnormally. In these periods, the deficiencies of the analytical framework of Economics appear and become more blatant than before. In these cases, within the economics, there is strife. The dominant version of Economics faces an ‘internal subversion’. Thus, there appears within Economics also a Heterodoxy. The latter is practically a heresy: it shares several articles of faith with Orthodoxy, but it disagrees with some others.

In this way, around the 1929 crisis, Keynesianism emerged as a heterodoxy; that is as the dispute within Economics of previously dominant Neoclassicism. Keynesianism proceeded to become the new Orthodoxy for the whole period from mid-war till the global crisis of 1974. Then, in the mid-1980s it was first challenged and subsequently dethroned by a very dogmatic and conservative version of Neoclassicism, Neoliberalism. Rational Expectations, infatuation with mathematization without considering its realism, belief in the perfect functioning of markets (efficient market hypothesis) etc. are its main features. Keynesianism – the previous Orthodoxy – became a Heterodoxy.

However, Neoliberalism – because of its unrealistic assumptions – has serious problems in instructing economic policy. That is, it was good as a religious form of preaching economic theory but was not very fit to make economic policy and face practical matters as many of its fundamental assumptions (e.g. rational expectations, perfect information, perfect markets, and so on) are very unrealistic hypotheses. And on these very unrealistic hypotheses, you cannot construct economic policy and face practical problems. So quite early, pure Neoliberalism was actually confined to the economics departments, but in policy making, more practical breeds were used. Thus, another ‘internal rebellion’ within Economics emerged: Keynesianism made a comeback in the version of New Keynesianism. The latter, in the beginning, was more of a Heterodoxy. But soon, even before the global crisis of 2008, it became the new Orthodoxy. This new orthodoxy took the form of the New Macroeconomic Consensus, which is a hybrid between a mild Neoliberalism and the conservative New Keynesianism. In a nutshell, the New Macroeconomic Consensus Orthodoxy is Keynesian in the short-run (accepting the existence of frictions and disequilibria and thus the efficacy of economic policy) and Neoliberal in the long-run (believing in rational expectations and self-equilibrating markets). Additionally, New Keynesianism reintroduces the use not only of monetary policy (something that Neoliberal Monetarism also accepted but Neoliberal New Classicals rejected) but also of fiscal and industrial policy (which are anathema for Neoliberals). And, later, the use of protectionist foreign economic policies is also introduced (another anathema for Neoliberalism). However, even the new Orthodoxy is being tainted by economic reality and especially economic turbulence and crises. For example, it faces serious difficulties in the current era of persistent inflation, weak growth, increasing imperialist rivalries etc.

I think that all these are proof of the general failure of Economics (in all their Orthodox and Heterodox versions) to adequately comprehend the economy and especially economic crises.

For example, all versions of Economics in the era of the Great Moderation (in the beginning of the 21st century) maintained that economic cycles and economic volatility in general (let alone crises) have been completely tamed if not extinguished. In this vein and in more practical terms, the IMF declared in October 2007 that “in advanced economies, economic recessions had virtually disappeared in the post-war period”. And then there was astonishment because the 2008 crisis erupted. Nobel Prize winner and top Chicago Neoclassical economist Eugene Fama declared: “We don’t know what causes recessions. I’m not a macroeconomist, so I don’t feel bad about that. We’ve never known. Debates go on to this day about what caused the Great Depression. Economics is not very good at explaining swings in economic activity… If I could have predicted the crisis, I would have. I didn’t see it. I’d love to know more what causes business cycles.”

The failure of Economics (both in their Orthodox and Heterodox versions) to comprehend the economic crisis stems from their very methodology. Despite their musical chairs games (between old and new Orthodoxies and Heterodoxies), Economics fail to comprehend the modus operandi of the economy. This lack of explanatory power is particularly evident during the more critical periods of the economy: economic crises.

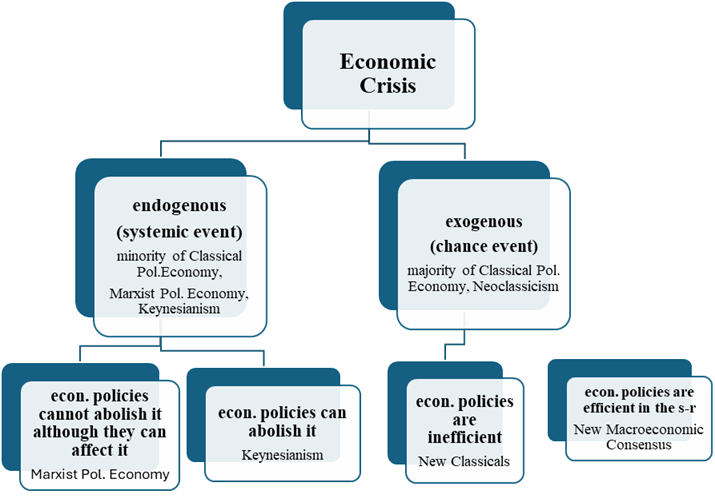

Table 3 summarises the way the main schools of economic thought approach the issue of economic crisis.

Table 3: Schools of economic thought & the economic crisis

There are two different fundamental approaches to the issue of economic crisis.

The one is to say that economic crisis is endogenous (it is a systemic, a normal feature of the capitalist system). This has been argued by the minority of classical political economy, Marxist political economy, and also Keynesianism.

The other approach is to say no, the capitalist system is a perfect system like a Swiss clock. It doesn’t ‘lose’ time unless somebody behaves abnormally. So crisis can only occur because of exogenous causes and chance events. This is the route followed by the majority of Classical Political Economy and also by a Neoclassicist.

There are differences also regarding the role and efficiency of economic policy in crisis. The Marxist Political Economy argues that economic policies cannot abolish economic crises, although they can affect them. Keynesianism argues that economic policies can practically abolish economic crisis. On the other hand, the New Classicals argue that economic policies are totally inefficient and irrelevant. They cannot affect anything. And of course, the New Macroeconomic Consensus in the short run is keynesian. That is, it argues that economic policies are efficient in the short run-in confronting economic crisis.

Essentially, Neoclassicism believes that capitalism is a perfect system (a Swiss clock) that never fails (and falls into crisis). Crises occur because some agents do not obey the normal market behaviour (hence they distort the perfect functioning of the market). Capitalism is a perfect and self-equilibrating system.

Keynesianism believes that capitalism may fall into crisis (possibility theory of crisis) because its anarchic nature permits agents to function irregularly. However, wise state supervision can either avoid crises or solve them. Capitalism is the best system, but it is not perfect and thus has to be saved from its own contradictions.

These approaches have failed not only in the last crisis but also in the previous ones. Their failure stems from their common foundations of Economics:

- Understanding of the economy as a ‘play’ between individuals fails to grasp its social dimension and particularly the role of class struggle. It fails also to link economic and social and political processes.

- Their belief that capitalism is the best socio-economic system leads to either ignore its fundamental deficiencies and contradictions or think that they can be rectified.

- Their emphasis on the sphere of circulation ignores that the basis of the economy is the sphere of production. Thus, both Neoclassicism and Keynesianism ignore the critical role of profitability (the rate and the mass of profit) in the capitalist economy. Consequently, they cannot discern how falling profitability leads to economic crisis.

Contrary to both of them, Political Economy proposes a more realistic and credible understanding of the economy. The latter is not a ‘play’ between individuals but between antagonistic social classes. This class struggle within the economy has an inherent social nature and is necessarily linked with politics. Thus, Political Economy argues for a unified analysis of the economy, the society and politics.

Within Political Economy the Marxist Political Economy tradition offers a very realistic, sophisticated and coherent theory of crisis. It argues that capitalism is a system that passes from periods of booms to periods of bust. This is the normal functioning of the system as it exhibits cyclical fluctuations (economic cycles). Thus, crises are not an aberration but a normal characteristic. Moreover, state intervention can affect the eruption and the evolution of crises but it cannot extinguish their existence.

The main points of the Marxian theory of crisis can be summarized as follows:

- Economic crises are part of the normal functioning of the capitalist system (that is, they have endogenous [systemic] causes).

- This implies that crises are a usual and frequent event (that is, they are a systematic phenomenon).

- This does not imply that capitalism is in continuous crisis; nor that it is destined to collapse due to simply an economic breakdown. Rather, that capitalism passes from periods of boom (growth) to periods of bust (recession). This succession causes the fluctuations of economic activity (economic cycles) and is expressed both in the short-run economic cycles and in the long-run ones.

- The systemic causes of crises derive from the dominant sphere of production (and are subsequently expressed in the other spheres and not vice versus). They express the contradictions of capitalist accumulation, and they operate even without the effects of class struggle (i.e. crises appear even without workers’ militancy).

- Τhe basic determinant (systemic cause) of both the shοrt-run and the long-run economic fluctuations is the profit rate (and the linked to it mass of profits). The profit motive is the aim and, hence the determining factor in the operation of the capitalist system. Therefore, its fluctuations determine both the short-run and the long-run fluctuations of the accumulation of capital (grossly expressed in the fluctuations of investment and the GDP).

- The basic rule that determines the movement of profit is the Law of the Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall (TRPF). It provides the central direction. It co-exists in continuous struggle with a number of counter-acting tendencies. Their interplay causes both the long-run fluctuations (alteration between ‘golden eras’ of strong growth and deep structural crises) and the short-run fluctuations (alterations between growth and slump).

- Intra-capitalist competition takes place in view of rates of profit (each capitalist eyes his adversaries) and is crucially shaped by the firms’ technical structure. Therefore, technical change is the main determinant of competitive advantage. This crucial role attributed to technical change differentiates Marx from both A.Smith (he considered technical change but not in relation to the rate of profit) and D.Ricardo (he did not considered technical change in relation to the rate of profit)

- The crisis is both an expression of the problems of the capitalist system and a rectification mechanism.

- Problems: the very success of the system (its overaccumulation of capital) causes its failure (the inability to continue to accumulate). Its overextension leads it to surpass its social and technical limits (in the given period).

- Rectification: a process of destruction and reconstruction. Part of the system must be destroyed (e.g. bankruptcies) in order to leave space for its rebuilding.

This analytical framework has greater explanatory power than that of Economics as the debate on the recent global crisis proved.

A more detailed exposition of Marx’s theory of economic crisis is given below:

https://www.scribd.com/document/361000299/Marx-and-the-Theory-of-Economic-Crisis