T. Sabri Öncü and Güney DüzçayThis article first appeared in the Indian journal, Economic & Political Weekly, on 14 September 2024. Güney Düzçay ([email protected]) and T. Sabri Öncü ([email protected]) are economists based in Türkiye.Historically, central banks, like the Bank of England, were primarily established to finance wars and manage government finances—serving as the “government’s bank.” Later, they evolved to address commercial and financial crises through their role as lenders of last resort and their regulatory power, acting as the “bankers’ bank.” During the 20th century, particularly in advanced economies, central banks adopted new roles, such as moderating business cycles. While moderating business cycles has become a prominent function, it is important to remember that the

Topics:

T. Sabri Öncü considers the following as important: Article, Economics & Ideology, International & World, Long Read, money & banking

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

T. Sabri Öncü writes Argentina’s Economic Shock Therapy: Assessing the Impact of Milei’s Austerity Policies and the Road Ahead

Ann Pettifor writes Global Economic Governance: What’s “Growth” Got to Do with It?

T. Sabri Öncü writes From Chile in 1973 to Argentina and Türkiye in 2023: Economic Genocide Continues

T. Sabri Öncü and Güney Düzçay

This article first appeared in the Indian journal, Economic & Political Weekly, on 14 September 2024. Güney Düzçay ([email protected]) and T. Sabri Öncü ([email protected]) are economists based in Türkiye.

Historically, central banks, like the Bank of England, were primarily established to finance wars and manage government finances—serving as the “government’s bank.” Later, they evolved to address commercial and financial crises through their role as lenders of last resort and their regulatory power, acting as the “bankers’ bank.” During the 20th century, particularly in advanced economies, central banks adopted new roles, such as moderating business cycles. While moderating business cycles has become a prominent function, it is important to remember that the core purposes of central banks—addressing crises and acting as lenders of last resort—still remain central to their relevance.

Over the past three decades, central banks have increasingly focused on “price stability,” treating it as their primary objective within the framework of free capital mobility and floating exchange rate regimes. Other crucial goals, such as financial stability, full employment, economic growth, and development, have been relegated to secondary importance or entirely overlooked. This emphasis on “price stability” and the fine-tuning of short-term interest rates has become central to economic orthodoxy, particularly under inflation-targeting regimes that have been exported to developing countries since the 1990s. This approach is problematic for two main reasons: (i) prioritising price stability, along with unrestricted capital mobility and floating exchange rates, fails to address the key challenges of developing countries and restricts their policy space; (ii) the obsession with fine-tuning short-term interest rates—what Ben Bernanke (2002) aptly called a “blunt tool” in another context—diverts attention from the broader requirements of central banking in developing countries.

In what follows, we focus on Türkiye’s central banking challenges over the past six years. Beyond the “opportunity” we had to closely observe and live through these experiences, they offer a rich historical backdrop for understanding the requirements of a central banking framework in a developing country. With this focus, we first offer two broad lessons on central banking strategies and frameworks that we believe will be valuable for middle-income developing countries.

Broad Lessons

First, the historical context of policymaking is crucial, and developing countries must carefully manage their degree of integration into global finance. It is essential to closely monitor global and domestic financial cycles and prepare for what lies ahead by adjusting strategies, rules, and policies—not just interest rate policies.

Second, the policy framework of a developing country should be grounded in or accompanied by a macroeconomic framework that includes the balance of payments and the aggregate balance sheets of key sectors. The reactive unorthodox measures Türkiye employed in response to a series of crises make perfect sense within such a framework, as we will demonstrate below.

The problem is that these measures were reactionary, born out of turmoil, and not part of a well-designed strategy. They were introduced without any intellectual foundation or discussion among policymakers. As a result, they were neither well understood nor appreciated. These measures had to be contextualised, and they still do.

Contemporary discussions, which are reactions to previous reactionary measures, focus on rescinding these policies based on neoclassical/neo-liberal catechism, without attempting to draw any lessons. Here, we emphasise the need for a different framework—not just for understanding these unorthodox measures, but as a central tool to address the developmental needs and constraints of developing countries.

Historical Context: Importance of Global and Domestic Financial Cycles

Macroeconomics and central banking often operate with a short-sighted focus, dealing primarily with near-term economic developments and expectations. This focus is based on the firm belief that we understand the world we live in, its mechanisms, its origins, and where it is headed.

Since 2018, Türkiye has faced several currency crises and a global economic shock. In response, the country implemented numerous unorthodox measures and deviated from the usual practices of central banks (Cömert and Öncü 2023). However, public debate has remained confined to a mechanical understanding of monetary policy, with a narrow focus on central bank rates: whether the priority should be on growth and avoiding recession by reducing rates or on disinflation and recovering from long-lasting capital flight by increasing rates. Today, the “economic genocide” camp has resurfaced (Öncü 2024), prioritising disinflation through austerity measures while ignoring the growing income and wealth inequality, suppressed wages, deteriorating balance sheets, and massive carry trade gains. They expect that by repairing the broken links with the rest of the world, capital will flow back to Türkiye just as it did in the past.

At times, it is necessary to step back and reframe the slow-moving parts, forces, structures, and mentality of global capitalism to avoid getting stuck with worn-out, outdated debates and practices in monetary policymaking. Türkiye has experienced a long credit cycle, beginning during the recovery phase of the 2001 crisis and entering its ending phase with the 2018 currency crisis (Figure 1). Accompanying this cycle, Düzçay and Öncü (2023) show that, over the last two decades, Türkiye has also witnessed the rise and fall of its local currency bond market (LCBM), fluctuations in its international reserves, and a two-decade-long real effective exchange rate appreciation–depreciation cycle, among other phenomena.

These cycles are examples of the “domestic financial cycles,” a term coined by BIS researchers to highlight the long-duration nature of credit cycles—longer than typical business cycles—and the macroeconomic and policy challenges they pose through their impact on balance sheets (Borio 2014, 2019). However, Türkiye’s experience was part of a broader phenomenon—the “global financial cycles”—a term that captures the synchronisation of capital flows, risk appetite, leverage cycles of financial intermediaries, and asset prices on a global scale. What predominantly drive these cycles are the United States (US) financial conditions, monetary policy, and the commodity, trade, and output cycles shaped by liquidity conditions and policy choices in Europe and China (Miranda-Agrippino and Rey 2022).

The key transmission mechanism between global and domestic financial conditions is the influence of US dollar liquidity and its cost on the exchange rates of developing countries. This transmission, in turn, loosens or tightens balance sheet constraints for domestic banks and firms, compelling domestic monetary policy to align with the stance of the Federal Reserve (Borio 2019).

The global financial cycle is undeniably powerful, but Türkiye’s rapid rise and fall in response to its fluctuations was not inevitable. It resulted from a deliberate choice regarding the extent of integration into global finance. Among its peers, Türkiye adopted one of the most orthodox approaches to this integration. Öniş and Senşes (2007) identified Argentina and Türkiye as prime examples of countries deeply committed to orthodox policies in their financial integration, attributing this to the weak developmental, regulatory, and redistributive capacities of their states:

The relative under-performers or moderate performers, … such as Argentina and Turkey, have been characterised by reactive states and weak state capacities … Over the past quarter century, these states have been reactive in the sense that they have single-mindedly followed orthodox, neo-liberal prescriptions without attempting to explore alternative forms of openness and degrees of integration into the global economy.

Notably, these two countries have experienced some of the most severe economic swings among their peers in the past decade, and intriguingly, both have recently returned to (neo-)liberal agendas as a perceived solution. There are lessons here for those who are willing to see them.

The natural corollaries of the financial cycles are “medium-term policy horizon”, “more holistic macro-financial stability framework,” and “macroprudential tools or capital controls” (Miranda-Agrippino and Rey 2022; Borio 2019). Moreover, the global cycles imply for developing countries to understand technological and industrial policies in central economies that would drive the next cycle of cross-border flows in order to generate macro strategies and policies. Developing countries should not hesitate to manage the degree of integration into global finance by changing the rules of the game in their jurisdictions and using intervention and control tools. They also have the right and need to prepare for what is going to come, by adjusting their strategies and policies—not just their interest rate policies.

A Simple Macroeconomic Framework

Global capitalism, with its current level of development and integration, does not allow any country to be completely insulated from the economic cycles of central economies. Table 1 provides a framework for understanding the global constraints, arising mainly from the cycles of central economies, on the developing country’s central banks. It is based on an equation derived from the balance of payments identity combined with the aggregate balance sheets of key sectors. For details, interested readers can refer to Páles et al (2011). In our approach, we use a slightly adjusted derivation and distinguish between official and private sector aggregates on either side of the equation.

The table illustrates the components of these aggregates. Official sector aggregates can be considered partly under the control of central banks, treasuries, or other relevant bodies, while private sector aggregates respond to (i) economic conditions; (ii) key prices such as interest rates and exchange rates, which can be influenced by the official sector; and (iii) credit policies and liquidity measures of the relevant bodies. It is also important to note that items within the private sector can and should be regulated to adjust the degree of global financial integration. Overall, all items of the aggregates listed in the table can be regulated or monitored for policymaking purposes, influencing various policy choices.

Orthodoxy in economics generally suggests a monetary regime in which all items of the aggregates in the table, except for Item 6, should be minimally regulated and left to the “invisible hand of the market.” Central banks are expected to perform their countercyclical or gatekeeper role through interest rates, assuming that “the blunt tool” is sufficient. The adoption of macroprudential tools or some capital flow restrictions since the global financial crisis of 2008 has been merely a patch and has not fundamentally altered the underlying mentality.

What Türkiye experienced in the last six years has demonstrated that the most important tools (reserves, interest rates, exchange rates, and credit policies) cannot be controlled and used effectively in emergencies or during the declining phase of a credit cycle without redefining the rules and boundaries regarding private capital flows. Yılmaz Akyüz (2017), with great insight, pointed out just one year before Türkiye’s first severe currency crisis that lessons learned and measures implemented since the Asian Crisis of 1997 would be inadequate, as they entailed deeper global financial integration for emerging market economies. He concluded that there are, practically, “two options in the event of a serious liquidity crisis—seek assistance from the IMF and central banks of reserve-currency countries or engineer an unorthodox response,” adding that “most emerging economies … appear to be determined not to go to the IMF again.” Türkiye did not resort to IMF advice or funds, could not find help from reserve-currency countries, and thus engineered several unorthodox responses to a series of crises and severe capital flow reversals.

Without resorting to an exhaustive summary of events (see Cömert and Öncü 2023, for details), let us summarise the main deviations from orthodoxy and match some of the important moves to the items in the table. Note that, thanks to the 2001 banking crises and global trends in banking regulations, Türkiye generally did not allow any sizeable net FX position (Item 6) for the banking sector. In 2009, as a response to the global crisis, Türkiye permitted non-exporter firms to borrow in FX from domestic banks.

Thanks to the low-interest rate environment in the 2010s, the non-financial private sector (NFPS) accumulated large FX debt. At the beginning of 2018, when monetary policymakers were struggling with impending capital flights and exchange rate pressures, the freedom for non-exporters to borrow in FX was withdrawn (Item 5). This move, however, was too late. Over the next five years, the NFPS gradually deleveraged in terms of FX debt, with constant pressure on reserves and exchange rates. The moral of this story is that the FX leverage of the NFPS is a binding constraint on monetary policymaking.

It is interesting to note that when Türkiye was hit by a currency crisis in August 2018, the immediate response from policymakers was to limit the size of FX swaps between the banking sector and non-residents (Item 7). These restrictions were further tightened in 2020 amid the turmoil caused by the pandemic. Concurrently and inter-connectedly, since 2018, foreign participation in the LCBM and domestic equity markets has gradually diminished (Items 4 and 3).1 In response to FX swap restrictions, the central bank had to step in to substitute for non-residents, as the banking sector faced a chronic FX deficit on its balance sheets that needed to be offset by off-balance sheet FX surpluses. Consequently, new facilities and markets were established between the banks and the central bank (Item c).

In late 2021, monetary policymaking was dominated by the “growth at all costs” camp. Confident that foreign participation in domestic markets was minimal, they attempted to swim against the tide by reducing interest rates. However, their approach soon proved flawed, resulting in a dramatic exchange rate blowout (see Cömert and Öncü 2023, for a detailed description of the event), along with significant deposit dollarisation and inflationary pressures. In response, several measures were introduced: FX rate-protected domestic deposits (Item 2), the appropriation of export revenues (Item 1), and restrictions on credit complemented by liquidity measures to support low rates in government borrowing. These actions enabled tighter control over exchange and interest rates, while credit policies were partially relaxed in 2022 in anticipation of the upcoming elections.

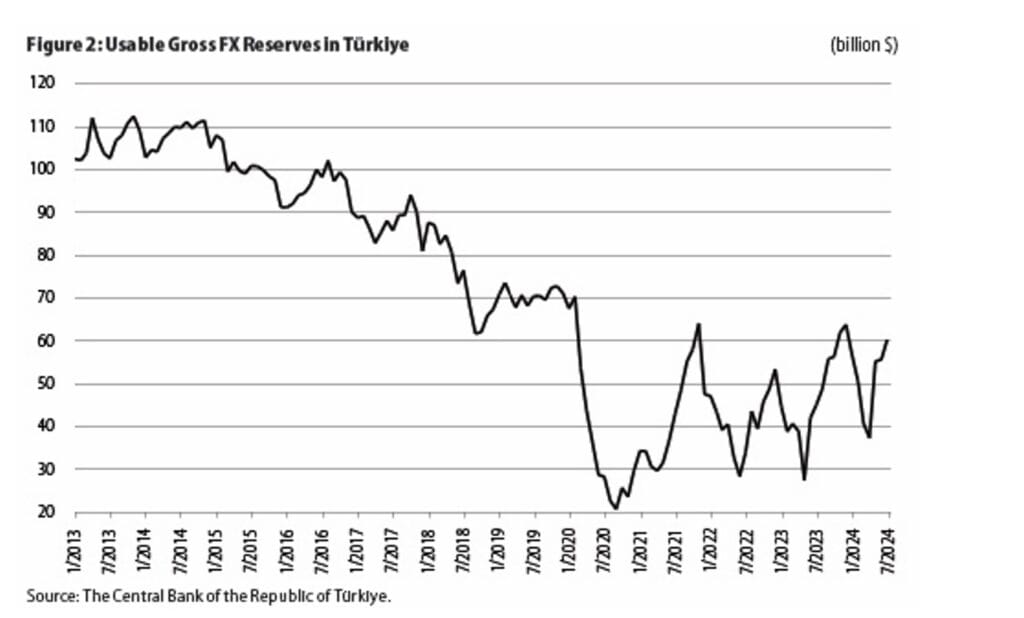

Nevertheless, the “growth at all costs” camp eventually faced the reality of depleted usable international FX reserves at the central bank, particularly around the time of the 2023 elections (Figure 2, p 13). This situation prompted a shift towards “orthodoxy,” albeit with a mixed set of regulations and policies, echoing the brief return to orthodoxy seen at the end of 2020.

This time, however, orthodoxy has returned with a vengeance, with a harshness that would make even the IMF jealous. The central bank’s return to orthodoxy, on the other hand, was only in interest rate policy, while the rest remains rhetoric, as the money plumbing does not allow for free-floating exchange rates or relaxing other capital flow restrictions. Wisely, some of those restrictions on capital flows were left in place. However, the anticipated capital flows were insufficient to counterbalance the depressionary effects of high interest rates. The interesting point is the prevailing ignorance or negligence regarding experiences with capital flow restrictions in both public debate and policymaker circles, coupled with the desire to swiftly return to orthodoxy with the expectation of a resurgence of capital flow bonanza days.

We believe it is time for Türkiye to awaken. The moral of this story for its peers is that inflation targeting or any other framework originating in capitalist centres does not work for us, and we need a different framework for monetary policies that takes into account developmental needs and global financial constraints.

Conclusions

In a recently published article, Freeman et al (2024) studied and showed that the production of scientific knowledge has been decentralising and dispersing across countries over the years. The exception is “economics,” which exhibits a trend of institutional concentration and an emphasis on ideas from a small group of schools. This is neither original nor surprising for those familiar with the field. Although we cannot prove it, we have every reason to suspect conflicts of interest between academia, policymakers, and capitalist groups. Certain ideas are more favourable to those with the means to promote them.

As the Financial Times Editorial Board (2024) aptly puts it: “Narrow gatekeeping and a steep hierarchy of prestige foster groupthink overseen by a self-perpetuating priesthood.” The products of that priesthood are what we call orthodox ideas. The modern central banking framework and strategies in developing countries are the flawed offspring of these ideas. They fail to address the main constraints of developing countries: the structural reliance on imports of high value-added goods, frontier technologies, and finances from capitalist centres, as well as the hierarchical nature of the global monetary order and dependence on external whims.

Policies based on such frameworks, such as raising or lowering interest rates, do not work as intended without managing the degree of integration into global trade and finance chains. Furthermore, these policies are not neutral in their effects on different social classes; they almost always increase income and wealth inequality.

Note

1 Akyüz (2017) specifically identified the rising share of foreign participation in the LCBM and shallow equity markets of emerging economies as a primary source of vulnerabilities and a channel for deepening financial integration.

References

Akyüz, Yılmaz (2017): “The Asian Financial Crisis: Lessons Learned and Unlearned,” Ekonomi-tek, 6.2 1-11.

Bernanke, Ben S (2002): “Asset-Price ‘Bubbles’ and Monetary Policy.”

Borio, Claudio (2014): “The Financial Cycle and Macroeconomics: What Have We Learnt?” Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol 45, pp 182–98.

— (2019): “A Tale of Two Financial Cycles: Domestic and Global,” Lecture at the University of Zurich, mimeo.

Cömert, Hasan and T Sabri Öncü (2023): “Understanding Recent Central Banking and Currency Crises in Turkey from the Dilemma Perspective,” (in Turkish), METU Studies in Development, 50, June, pp 1–57.

Düzçay, Güney and T Sabri Öncü (2023): “India’s Inclusion in the JP Morgan GBI-EM Indices: A Path to Eden or Just Another Sin?” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 58, No 47, pp 13–17.

Financial Times Editorial Board (2024): “Is Economics in Need of Trustbusting?” 30 August.

Freeman, Richard B, D Xie, H Zhang and H Zhou (2024): “High and Rising Institutional Concentration of Award-Winning Economists.”

Miranda-Agrippino, Silvia and Hélène Rey (2022): “The Global Financial Cycle,” Handbook of International Economics, Vol 6, Elsevier, pp 1–43.

Öncü, T Sabri (2024): “From Chile in 1973 to Argentina and Türkiye in 2023 Economic Genocide Continues,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 59, No 19, pp 10–13.

Öniş, Ziya, and Fikret Senşes (2007): “Global Dynamics, Domestic Coalitions and a Reactive State: Major Policy Shifts in Post-war Turkish Economic Development,” METU Studies in Development, 34, December, pp 251–86.

Páles, Judit, Zsolt Kuti and Csaba Csávás (2011): “The Role of Currency Swaps in the Domestic Banking System and the Functioning of the Swap Market during the Crisis,” No 90, MNB Occasional Papers.