Summary:

In "De-growth vs a Green New Deal," Robert Pollin relies on the same blurring of distinctions that Robert Solow employed 46 years earlier in his condemnation of The Limits to Growth as "bad science." Nicholaus Georgescu-Roegen pointed out Solow's obfuscation in the article that inspired the term "degrowth." That historical context is vital for understanding why Pollin's "blueprint for ecological salvation" is no advance over Solow's. In "Is theEnd of the World at Hand" Solow scolded the "bad science" of The Limits to Growth report on the grounds that its authors' model assumed "that there are no built-in mechanisms by which approaching exhaustion [of resources] tends to turn off consumption gradually and in advance."[1] Solow cited increases in the productivity of natural resources to

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

In "De-growth vs a Green New Deal," Robert Pollin relies on the same blurring of

distinctions that Robert Solow employed 46 years earlier in his condemnation of

The Limits to Growth as "bad

science." Nicholaus Georgescu-Roegen pointed out Solow's obfuscation in

the article that inspired the term "degrowth." That historical

context is vital for understanding why Pollin's "blueprint for ecological

salvation" is no advance over Solow's.In "De-growth vs a Green New Deal," Robert Pollin relies on the same blurring of distinctions that Robert Solow employed 46 years earlier in his condemnation of The Limits to Growth as "bad science." Nicholaus Georgescu-Roegen pointed out Solow's obfuscation in the article that inspired the term "degrowth." That historical context is vital for understanding why Pollin's "blueprint for ecological salvation" is no advance over Solow's. In "Is theEnd of the World at Hand" Solow scolded the "bad science" of The Limits to Growth report on the grounds that its authors' model assumed "that there are no built-in mechanisms by which approaching exhaustion [of resources] tends to turn off consumption gradually and in advance."[1] Solow cited increases in the productivity of natural resources to

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

In "Is theEnd of the World at Hand" Solow scolded the "bad science" of The Limits

to Growth report on the grounds that its authors' model assumed "that

there are no built-in mechanisms by which approaching exhaustion [of resources]

tends to turn off consumption gradually and in advance."[1]

Solow cited increases in the productivity of natural resources to illustrate

the importance of the price system as the built-in mechanism of capitalism for

"registering and reacting to relative scarcity."

According to

Solow, between 1950 and 1970, consumption of iron in the U.S. increased by 20

percent while the GNP roughly doubled. Consumption of manganese rose by 30

percent. Copper consumption increased by one-third, as did lead and zinc

consumption. These increases represented productivity gains ranging from 2

percent per annum for copper, lead and zinc to 2.5 percent for iron. Meanwhile,

productivity of bituminous coal rose by 3 percent a year during the same

period.

There were, Solow

conceded, some "important exceptions, and unimportant exceptions."

Among the more important ones was petroleum, "GNP per barrel of oil was

about the same in 1970 as in 1951: no productivity increase there."

Nevertheless, Solow was confident that "no one can doubt that we will run

out of oil… [s]ooner or later, the productivity of oil will rise out of sight,

because the production and consumption of oil will eventually dwindle toward

zero, but real GNP will not."

Solow acknowledged

another important exception to his productivity argument: pollution. The price

system is flawed, he admitted, in its failure to charge polluters "for

using the environment to carry away waste." Thus "the waste-disposal

capacity of the environment goes unpriced; and that happens because it is owned

by all of us, as it should be." Solow saw this problem as easily

remediable through common sense regulation, user taxes and investment in pollution

abatement.

Georescu-Roegen's

response to Solow, in the 1975 article, "Energy and Economic Myths"

emphasized the distinction between growth and development:

…if we are talking about growth, strictly speaking, then the depletion of resources is inherent in the process by definition. Solow's exposition of why he thought The Limits to Growth was bad science relied on blurring the distinction between qualitative development and quantitative growth and counting the former as an instance of the latter. This sort of legerdemain is, of course, standard in so-called growth economics.[2]In 1979, Jacques Grinevald and Ivo Rens translated "Energy and Economic Myths" and included it with two other articles on bioeconomics in a book titled Demain La Décroissance: Entropie – Écologie – Économie.[3] The term, décroissance occurs in the translation of a section in which Georgescu-Roegen criticized what he considered "the greatest sin of the authors of The Limits" -- their exclusive focus on exponential growth, which fosters the delusion that "ecological salvation lies in the stationary state."

In opposition to

that view, Georgescu-Roegen argued, "the

necessary conclusion of the arguments in favor of that vision [of a

stationary state] is that the most

desirable state is not a stationary, but a declining one (emphasis in

original)." His argument was not that ecological salvation lies

instead in a declining (or "degrowth") economy. It was that there can

be no "blueprint for the ecological salvation of the human species."

as he elaborated in the subsequent paragraph:

Undoubtedly, the current growth must cease, nay, be reversed. But anyone who believes that he can draw a blueprint for the ecological salvation of the human species does not understand the nature of evolution, or even of history -- which is that of a permanent struggle in continuously novel forms, not that of a predictable, controllable physico-chemical process, such as boiling an egg or launching a rocket to the moon.

Pessimistic?

Perhaps, but it is less so if one keeps in mind Georgescu-Roegen's injunction

against blurring the distinction between quantitative development and

quantitative growth. There are no "built-in mechanisms," either of

the price system, of the regulatory and tax regime or of a Green New Deal that

can ensure ecological salvation because the latter requires not blueprint or a

formula but "permanent struggle in

continuously novel forms."

So how does

Pollin's Green New Deal stack up compared to Solow's "built-in

mechanism" of the price system? First, with regard to the distinction

between qualitative development and quantitative growth, Pollin gives no

indication of being aware of Georgescu-Roegen's (and Schumpeter's) distinction.

Instead, Pollin does distinguish between "some categories of economic

activity [that] should now grow massively" such as those associated with

clean energy and others, such as "the fossil-fuel industry that needs to

contract massively." Charitably, this shift may be interpreted as at least

tacitly acknowledging a qualitative development rather than simply a

quantitative growth/contraction. But because Pollin doesn't make that

distinction explicit, his concluding comparison of "average incomes"

from a degrowth scenario vs his Green New Deal is fundamentally flawed.

Pollin refers to the

process by which this simultaneous massive growth of clean energy and massive

contraction of fossil fuel is supposed to occur as "decoupling." Decoupling

is a synonym for what Solow called natural resource productivity. The

calculation is the same -- national income divided by the quantity of the

resource consumed or waste emitted. But decoupling,

as Pollin uses it and as it is commonly used, is a deceptive term. Economic

activity is not decoupled from the

consumption of fossil fuel, as Pollin claims. It is the rate of change of economic activity that is decoupled from the rate of change of fossil fuel consumption.

Resource

productivity (or rate-of-change decoupling) is analogous to labour productivity,

as Solow pointed out, and that parallel suggests a method for side-stepping the

measurement complications that arise from GDP. One can instead calculate the decoupling

of carbon dioxide emissions from aggregate employment. This alternative

restores the original sense of productivity measurement, which was in terms of

physical inputs and physical outputs rather than dollar values.[4]

I will discuss the measurement complications later, in connection with incomes

but first, let's review Pollin's optimistic account of the prospects for "absolute

decoupling."

According to

Pollin, citing a blog post from the World Resources Institute[5],

"between 2000 and 2014, twenty-one countries, including the US, Germany,

the UK, Spain and Sweden, all managed to absolutely decouple GDP growth from CO2

emissions…" This did not happen.

GDP growth was not decoupled from CO2

emissions. What was "decoupled" was GDP growth from emissions growth and, more precisely, from growth

in one commonly-used estimate of emissions.

Such claims need

to be examined for their attention to two important subtleties: territorial

emissions can be reduced by outsourcing those emissions to an offshore

supplier. What about emissions embodied in trade? And GDP growth incorporates

all kinds of distortions (we'll get to those). What about a more meaningful

indicator of the level of economic activity, such as total employment?

Of the twenty-one

countries claimed by the WRI to have achieved "absolute decoupling"

between 2000 and 2014. Slovakia, Switzerland and Ukraine had increases in their

consumption-based CO2 emissions that adjust for emissions embodied in trade.

Bulgaria's consumption-based emissions were unchanged from 2000-2014. Portugal,

Romania and Ukraine had declines in aggregate employment. Denmark had no

increase in employment. There was no consumption-based data for Uzbekistan and

its reported employment data (ILO) does not appear credible, so it can be

excluded from the analysis.[6]

That leaves 13

countries with "absolute decoupling" of the rate of change of employment

and the rate of change of consumption-based emissions. Of those 13, the Czech

Republic had reductions in average annual hours that exceeded the increase in

employment. Finland just squeaked through into absolute decoupling territory if

defined by changes in aggregate working hours and consumption-based Co2

emissions.

Twelve of the 21

countries touted by WRI meet the more rigorous rates of change decoupling

criteria. Again, no countries decoupled employment growth from CO2 emissions.

The average gap between growth in employment and decline in emissions, weighted

for the size of employed work force in 2014, was a bit less than half of the

gap between GDP growth and change in territorial emissions. (17.6 percent

versus 37 percent). That is 12 out of the 63 countries that had emissions of at

least 12 MtC/yr in 2000, as did Bulgaria. In other words, 51 other countries

among the top 63 did not have absolute decoupling of employment growth and

emissions decline.

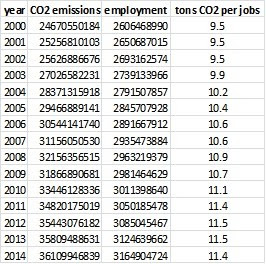

In spite of those

21 or 12 countries that "absolutely decoupled" the rates of change of

GDP/employmnt and CO2 emissions between 2000 and 2014, tons of CO2 emitted

globally per employment-year rose from 9.5 to 11.4. That is neither an absolute

decoupling nor a relative one. That is a 20% intensification of emissions per job, a decline in the productivity of emissions. Meanwhile, China's

increase in consumption-based carbon dioxide emissions from 2000 to 2014 was 8

times the total decrease of all 21 counties for whom WRI proclaimed

"absolute decoupling" of "GDP and energy-related carbon dioxide

emissions."

|

| Global CO2 emissions intensity of employment 2000 - 2014 |

On the Rebound

Pollin's treatment

of the so-called "rebound effect" is also inadequate. This

phenomenon, also known as the Jevons Paradox is not a separate, add-on effect

to productivity and should not be treated as such. It is an intrinsic part of

the "built-in mechanism" of the price system. Again, the use of

synonyms and euphemisms adds to the confusion. Just as decoupling is a synonym

for productivity, the productivity of resources is another way of referring to

the efficiency or economy of their use. When the use of a resource, such as a

fuel, is made more economical through technological innovation, its relative

cost may fall even though its absolute price may be rising. Thus increased

efficiency (or productivity) may lead to increased consumption. Separating out

the rebound effect from the analysis of productivity or of rate-of-change decoupling

is about as plausible as separating out the butter from a baked cake.

In formulating the

"paradox" of greater efficiency leading to increased consumption in

1865, W. S. Jevons described it as "principle recognised in many parallel

instances," particularly that of labour-saving machinery eventually

increasing employment.[7]

But fuel efficiency and labour saving machinery are not merely two

"parallel instances," they are two defining moments in a single,

continuous positive feedback loop.

Pollin speculates

that rebound effects from efficiency gains will be modest, at least in

developed countries, but he still argues it is crucial that "all

energy-efficiency gains be accompanied by complementary policies (as discussed

below), including setting a price on carbon emissions to discourage fossil-fuel

consumption." I would agree with the need for regulation or taxation to

discourage fossil-fuel consumption but would insist that putting a price on

carbon emissions will also put a damper on the jobs that increased fuel

consumption would otherwise generate. Until the link between fossil-fuel

consumption and jobs is decisively broken, you can't choose to dial down one

without affecting the other. One can't assume post-transition availability and

relative prices of clean energy sources during the transition!

This point is

missed in virtually every discussion of the rebound effect or Jevons Paradox.

There are not two, "parallel" rebound effects, one for fuel consumption

and one for employment. The rebound of employment drives the rebound of fuel

consumption, which in turn drives the rebound of employment. To decouple the

employment rebound from fossil fuel

consumption requires the fantasy that one can substitute clean energy supplies that do not yet exist for fossil fuels that

do.[8]

Comparing Average Incomes

In his criticism

of Peter Victor's Managing without Growth,

Pollin argues that per capita GDP in 2035 for a degrowth scenario would

"plummet" to little more than half the 2005 level, while under

Pollin's proposed clean energy investment programme, "average incomes

would roughly double." The second chapter of Darrell Huff's 1954 classic, How to Lie with Statistics is all about

averages, so I can't claim originality for this point: Pollin's otiose comparison

of average incomes under the two

scenarios says nothing but insinuates too much about distribution. To mix a few

metaphors, a rising tide lifts all boats as the sparrows pick away at the

remnants of "oats" that have "trickled down" from the

horse.

There are several

other egregious distortions in Pollin's comparison of "average

incomes": leisure time doesn't count as income and "average

income" doesn't say anything about what a person has to give up in time and

effort to receive it. GDP is not some magic cake that just appears and gets

doled out in equal-sized slices. As Maurice Dobb pointed out quite some time ago:

It is not aggregate earnings which are the measure of the benefit obtained by the worker, but his earnings in relation to the work he does — to his output of physical energy or his bodily wear and tear. Just as an employer is interested in his receipts compared with his outgoings, so the worker is presumably interested in what he gets compared with what he gives.[9]In comparing the projected average incomes of his clean energy investment programme and Peter Victor's degrowth scenario, Pollin appears to have set aside his earlier solidarity with the "values and concerns of degrowth advocates" particularly regarding GDP as a measure of wellbeing:

…there is no disputing that it fails to account for the production of environmental bads, as well as consumer goods. It does not account for unpaid labor, most of which is performed by women, and GDP per capita tells us nothing about the distribution of income or wealth.

Dividing up GDP into per capita income doesn't eliminate these problems

– or others. In 1995 the Atlantic Monthly published an article

that asked, "If the GDP is up, Why is America Down," a great

riff on the title of Richard Fariña's novel, Been Down So Long, It

Looks Like Up To Me.[10] That

article explained a lot of what's wrong with the economy and what's wrong with

economics:

Once you start asking 'what' as well as 'how much' -- that is, about quality instead of just quantity -- the premise of the national accounts as an indicator of progress begins to disintegrate, and along with it much of the conventional economic reasoning on which those accounts are based.

Questions about

distribution, about quality vs. quantity of goods, the production of

environmental "bads" and the disregarding of unpaid labor only skim

the surface of what is wrong with the GDP. Those questions focus on the

symptoms. A deeper understanding of the root causes reveals that the

discrepancy between the measurement and the thing that is purported to be

measured may be orders of magnitude.

Basic accounting errors of double-counting and

"asymmetric entry" abound in the compilation of National Income and

Product Accounts. These fundamental errors have been highlighted by Irving

Fisher, Simon Kuznets, Paul Samuelson, Roefie Hueting, Angelo Antoci, Stefano

Bartolini and others. These mismeasurements are not one-off discrepancies –

they also establish a positive feedback loop of incentives for cumulative misallocation

of resources and miscalculation of outcomes.

In his 1948 critique of the Commerce

Department's National Income and Product Accounts, Kuznets focused on the

double counting of intermediate goods, especially in the form of military

expenditures and government services that facilitate commercial activity.[11]

Hueting identified the problem of asymmetric entering in which expenditures on

remediating environmental damage adds to GDP even though no subtraction was

recorded for the damage itself.[12] Antoci

and Bartolini analyzed the cumulative role of negative externalities in

boosting GDP growth.[13]

It is not only that GDP doesn't distinguish between

goods and bads. Systematic mismeasurement puts a premium on expanding the proportion

of bads to goods.

Over a century ago, Fisher, one of the most

influential American economists in the early 20th century, maintained that

faulty definitions of income resulted in rampant double-counting errors. There

are three compelling reasons for not ignoring Fisher's views on income and

double counting. First, Fisher is an acknowledged pioneer of national income

accounting – his definitions of income need to be acknowledged, even if only to

show that they are not practicable or even are defective. Second, Fisher's

critique of the ill-defined "general concepts of income" addresses

precisely the "heterogeneous combination" of goods and services that

is standard in the GDP. Third, the recurrent examples of double counting

lend empirical support to Fisher's claim that the improper definition of income

inevitably results in such errors.

In The Nature of Capital and Income,

Fisher argued that the usual definitions of income fail one or both of the

tests of being both useful for scientific analysis and harmonizing with popular

usage.[14] The

pitfalls of those faulty definitions go largely unnoticed, making them

"all the more dangerous."

Fisher focused on two common concepts of income.

The first concept, money income, is reasonably adequate for commercial affairs

because the purpose of business is to make money. But making money is not the

purpose of households. Part of household production takes place outside of

monetary exchange and even monetary earnings have as their ultimate purpose the

purchase of food, clothing, housing and the like, which constitute the

household's real income.

The second concept, pertaining to real income, is

commonly defined in terms of both goods and services. Fisher criticized this

concept for its eclecticism and inconsistency. The procedure treats some items

-- such as fuel, food and apparel – as current consumption but apportions very

long-lived items such as dwellings as if they were being rented. This leaves a

variety of moderately durable items such as furniture or vehicles to be treated

in an ad hoc manner. Fisher concluded that "such a patchwork of

arbitrarily selected elements is incapable of furnishing any consistent,

reliable, and logical theory of income."

That patchwork is where double counting comes in.

Economists "have not known where to cease calling the concrete instrument

income and begin calling its use income instead. In their hesitation they have

in some cases ended by including both. By so doing they commit the fallacy of

double counting."

Fisher's alternative to the goods and services

concept was "to regard uniformly as income the service of a dwelling to

its owner, the service of a piano and the service of food; and in the same

uniform manner to exclude alike from the category of income the dwelling, the

piano, and even the food." The latter, he argued are "capital, not

income."

As logical and consistent as Fisher's definition of

income may appear in the abstract, it is hard to imagine how it could ever be

implemented in national income accounts. Monetary transactions occur when items

are purchased, not when they are actually consumed. Fisher's definition would

require a vast and highly subjective extension of financial record keeping.

Similarly, Commerce Department economists responded to Kuznets's critique,

conceding many of his points but stressing the technical difficulty of putting

an alternative into practice.

The arguments presented in defense of the goods and

services concept are usually framed in terms of expediency. Such expedients

have a limited shelf life, however. Typically, proponents of the monetized

goods and services concept cheerfully admit its perishability, logical frailty

and limited portability. "This process can never claim complete logical

watertightness," Colin Clark confessed in 1937, "but we can be

satisfied that it works well enough in practice for comparisons over periods up

to, say, twenty years, or for comparisons between communities whose ways of

living are not too widely different." Once the tabulations are up and

running, those caveats are ignored.

If you start with an accounting system that

systematically double counts some revenue items and doesn't count others, you

also have a system of perverse incentives to shift more and more effort,

investment and expenditures, over time, to the double-counted items because

that will project the illusion of more robust economic performance. For

apostles of growth, double counting is not so much a social accounting debacle

as it is a public relations triumph.

Investment Returns

Clearly Pollin presumes there is nothing inevitable

about the system of perverse incentives that engorges GDP and proposes that the

proceeds of growth can, in effect, be "siphoned off" to fund

investment in clean energy. In this vision, the transition to clean energy

would be funded by a portion of the increment of national income rather than

requiring diversion of a portion of the "principal" thus making

ecological salvation economically painless. Pollin's Green New Deal posits

investment in clean energy as a supplementary "built-in mechanism"

that will gradually wean GDP from dependence on fossil fuels (once "those

powerful vested interests", who "wield enormous political power"

have been defeated). The faster GDP grows, in this vision, the more rapid will

be the transition to clean energy because more growth will automatically result

in more investment.

The word "investment" does a lot a work

in the Pollin plan. What the term abbreviates is a complex process of

institutionalizing selection criteria for the funding of projects, project

design and budgeting, ranking and selection of competing projects, project oversight

and post-project evaluation of success in meeting objectives. There is not some

ready-made pool of self-evidently effective clean energy projects. The whole

process -- conducted presumably by hundreds of agencies operating in hundreds

of countries -- is subject to cronyism, administrative padding of costs, inept

selection criteria, mislabeling, miscalculation, lobbying, boondoggles,

administrative capture by powerful vested interests and outright embezzlement.

There is no "built-in mechanism" to guarantee a "trillion dollar

annual investment in clean energy" delivers what the name advertises.

In short, investment in clean energy is not "a

predictable, controllable physico-chemical process,

such as boiling an egg or launching a rocket to the moon." The successful

outcome of such a programme would require "a permanent struggle in

continuously novel forms" not simply the once-and-for-all defeat of those powerful

vested interests who wield enormous political power.

Deja vu all over again

Forty-six years ago, Robert Solow placed his faith

mainly in the "built-in mechanisms" of the price system, which, he

claimed, "tends to turn off consumption [of scarce

resources] gradually and in advance." Evidence for the success of this

mechanism was to be seen in the increasing productivity of a variety minerals

used as industrial inputs. But pollution presented an exception to this rule

because it escaped the price system. Solow offered a remedy for that defect –

investment in pollution abatement:

An active pollution abatement policy would cost perhaps $50 billion a year by 2000, which would be about 2 percent of GNP by then. That is a small investment of resources: you can see how small it is when you consider that GNP grows by 4 percent or so every year, on the average. Cleaning up air and water would entail a cost that would be a bit like losing one-half of one year’s growth, between now and the year 2000.

Robert Pollin's critique of degrowth and his proposed alternative of a Green

New Deal unwittingly recycles Robert Solow's 1973 rebuttal to The Limits

to Growth. Pollin substitutes the euphemistic "decoupling" for

Solow's more conventional "productivity." He acknowledges criticism

of GDP and then ignores those criticisms when comparing degrowth and Green New

Deal scenarios. He updates, refines and globalizes his investment target to one

trillion dollars from Solow's $50 billion, although both figures are presented

as approximately the same percentage of annual gross product.

Pollin's one major digression from the Solow blueprint is a curiously

nostalgic one. He stresses the need to defeat "powerful vested

interests" of the fossil fuel industry who "wield enormous political

power" and charges the degrowth perspective with "the critical error

of ignoring the reality of neoliberalism in the contemporary world." Yet Pollin

makes no suggestion about how those vested interests might be defeated or

"how to put capitalism back on the leash that prevailed during the ‘golden

age’ [before the era of neoliberalism]."

Speaking at a symposium on The

Limits to Growth at Lehigh University in October 1972, Robert Solow could

not have foreseen the military coup in Chile the following September that

ushered in the regime of neoliberalism nor the OPEC oil embargo a month later

that ushered in a new era of petro-political economy.

[1] Robert Solow, 'Is the End of the World at Hand?" Challenge, March/April 1973, pp. 39-50.

[2] Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, 'Energy and Economic Myths', Southern Economic Journal, January 1975,

pp. 347-381.

[3] Jacques Grinevald

and Ivo Rens, Demain La Décroissance:

Entropie – Écologie – Économie, Lausanne, 1979.

[4] Fred Block and Gene A. Burns, 'Productivity as a Social Problem:

The Uses and Misuses of Social Indicators', American

Sociological Review, December, 1986, pp. 767-780.

[5] Nate Aden, ‘The Roads to Decoupling: 21 Countries Are Reducing Carbon

Emissions While Growing GDP’, World Resources Institute blog, 5 April 2016.

[6] Consumption-based CO2 emissions estimates are from 'The Global

Carbon Budget 2017' updated from Peters, GP, Minx, JC, Weber, CL and Edenhofer,

O 2011. Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 8903-8908. Employment

estimates are from International Labour Organization, ILOSTAT, Key Indicators

of the Labour Market, Status in Employment.

[7] William Stanley Jevons, The

Coal Question, London, 1865.

[8] On decoupling as fantasy, see Robert Fletcher & Crelis Rammelt,

'Decoupling: A Key Fantasy of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda', Globalizations,

14:3, pp. 450-467. They write:

"[The]

dramatic disjuncture between the blind optimism of the decoupling proposal and

the daunting (thermodynamic, financial, and distributive) obstacles in the face

of its realization suggests that the concept works as a Lacanian fantasy,

presenting both the prospect of sustainable development at some unknown future

point and a convenient a priori explanation for why this aim is not achieved. …

"The pressing danger, of course, is that even if decoupling is

infeasible, it will take some time for this to be demonstrated to the

satisfaction of its proponents as well as those merely using it as a

smokescreen to continue business as usual for as long as they still can. Thus,

the decoupling fantasy may allow us to maintain an increasingly destructive

path with both the promise of success and demonstration of its impossibility

deferred into the future."

[9] Maurice Dobb, Wages,

Cambridge, 1928.

[10] Clifford Cobb, Ted Halstead and Jonathan Rowe 'If the GDP is up,

Why is America Down', Atlantic Monthly,

October 1995.

[11] Simon Kuznets, 'National Income: A New Version', The Review of Economics and Statistics,

August 1948.

[12] Roefie Hueting, 'Three Persistent Myths in the Environmental

Debate', Ecological Economics, 1996,

pp. 81-88.

[13] Angelo Antoci and Stefano Bartolini, 'Negative externalities,

defensive expenditures and labour supply in an evolutionary context', Environment and Development Economics,

October 2004.

[14] Irving Fisher, The Nature of

Capital and Income, New York, 1906.