Blog The dodgy economics behind expanding our airports Despite what airport executives say, expanding our airports won’t tackle unemployment or bring more money to the UK. By Alex Chapman 15 September 2020 Given the widely publicised collapse in international air travel, you’d be forgiven for assuming that expanding airports would be the last thing on aviation executives’ minds. Yet planning applications are currently under consideration for Leeds Bradford Airport and Southampton Airport; Bristol Airport just announced they are appealing North Somerset Council’s rejection of their plans; and Heathrow

Topics:

Alex Chapman considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

The dodgy economics behind expanding our airports

Despite what airport executives say, expanding our airports won’t tackle unemployment or bring more money to the UK.

15 September 2020

Given the widely publicised collapse in international air travel, you’d be forgiven for assuming that expanding airports would be the last thing on aviation executives’ minds. Yet planning applications are currently under consideration for Leeds Bradford Airport and Southampton Airport; Bristol Airport just announced they are appealing North Somerset Council’s rejection of their plans; and Heathrow Airport refuse to accept their substandard mega-expansion is dead in the water.

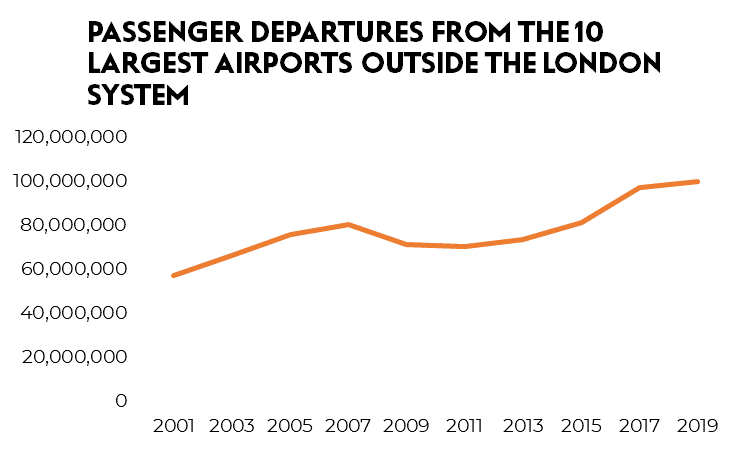

The climate case against all of these projects is obvious. Regional airports try to claim that their expansions won’t create new flights – rather, they’ll simply steal flights from other airports around the country. But it only takes one look at the data to debunk this myth. More airport capacity leads to higher passenger numbers – and higher emissions. The last financial crisis slowed passenger growth, but only temporarily, and the sector is banking on a similar recovery from Covid-19.

At the national level, the economic case for increasing airport capacity has long been flimsy – and in the midst of a global pandemic and crippling recession, it is even more so. Politicians extolling the virtues of air travel will often refer to the benefits for business, but in reality the proportion of flights taken for business trips has been declining consistently for almost two decades. In 2019, only 15% of UK departures were for international business purposes, and only 4% for domestic business. Around 75% of departures were for international leisure trips. Of this figure, the majority (62%) are UK residents, meaning that far more UK residents fly out for leisure than foreign residents fly in.

The picture at the non-London airports looking to expand is even more extreme. Take Leeds Bradford: in 2017 only 7% of departing flights were for business purposes. The vast majority (85%) were international leisure trips, of which only 22% were taken by foreign residents. The rest were UK residents on their way out. It’s a similar story at all of the regional airports proposed for expansion.

Now, let’s consider the impacts of the global pandemic. Covid-19 has forced businesses into a mass adoption of remote working and online conference calls, and there has been plenty of polling which suggests that business and employee behaviours have changed for good. Business air travel, and its future role at airports like Bristol, Leeds Bradford, and Southampton, only looks set to decrease.

This means that business travel does not and will not drive the economics of airport expansion – instead, we must consider the impacts on international tourism. UK travellers flying abroad and international travellers flying into the UK spend about the same amount – around £700 per person. But as more UK residents fly out than international tourists fly in, the UK operates a significant travel spending deficit. Indeed, about £30bn moves out of the economy every year due to international travel. And the problem is getting worse: after inflation, this deficit doubled between 2012 and 2019, driven almost exclusively by increasing numbers of passengers flying out of the UK. At the same time, spending on domestic tourism has flat-lined since at least 2006, despite significant growth in both the population and economy.

What regional airport expansion does do is provide competitive advantage to the international tourism market. Flying becomes cheaper and easier at a time when the domestic tourism, hospitality, and leisure industries are crippled by the impact of Covid-19. Where do we want people spending their money? Opening a new airport terminal that offers cheap flights out of the country just as we attempt to rebuild our economy is the worst possible timing.

The last defence of the ambitious airport executive is that new airport capacity creates new jobs. But it’s not that simple. When we looked at the expansion of Southampton airport, we found that the economic value of these jobs (worth around £50m) is actually wiped out by the cost of the associated carbon emissions (worth around £28m-£85m) – that’s if we assume these jobs will ever materialise.

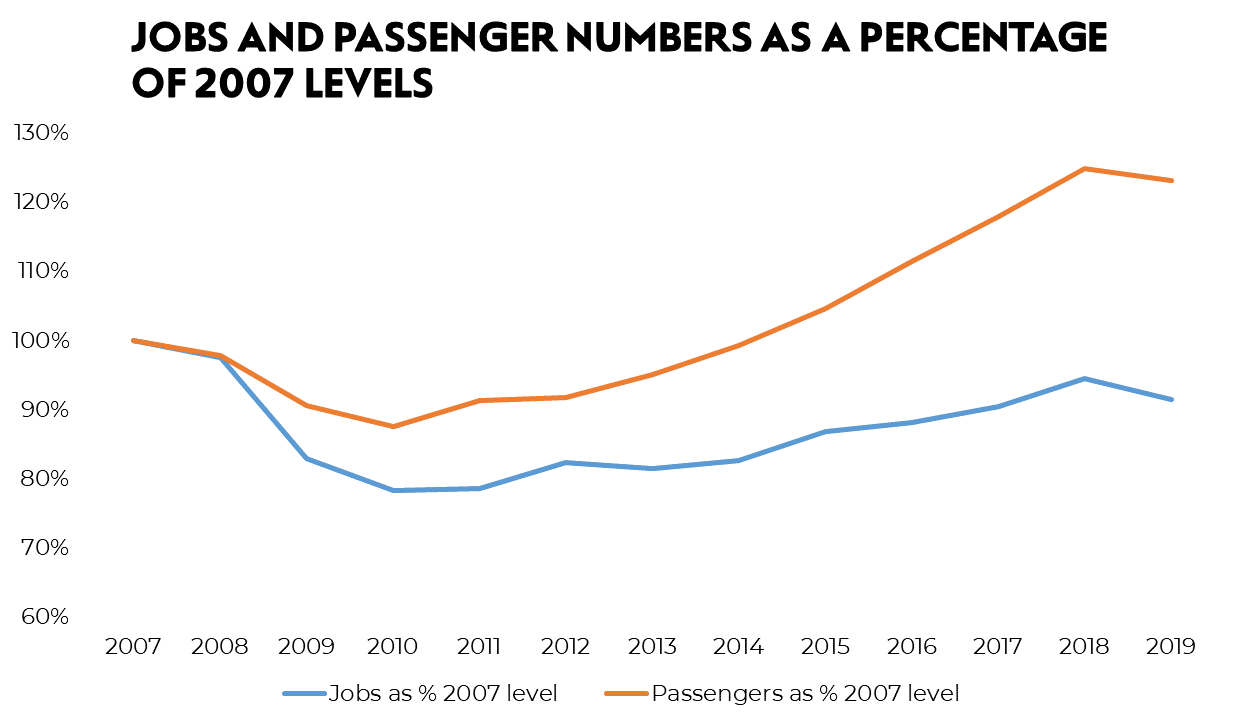

The issue with the promise of a plethora of airport jobs is the ongoing efficiency drive in the industry, driven by processes like automation. The ‘job intensity’ of aviation (ie, the number of jobs per passenger) has been falling consistently for more than a decade. As shown in the figure below, and discussed in our recent report on crisis support to aviation, sector jobs have never recovered to their peak in 2007, despite huge growth in passenger numbers. We already have plenty of evidence that this trend will continue, as airlines exploit this economic crisis as an opportunity to squeeze working conditions and pursue further ‘efficiencies’.

Even without the dangers of increasing carbon emissions, the economics of airport expansion don’t stack up. As we look down the barrel of the climate crisis, a global pandemic, and a collapsing UK hospitality sector, it’s possibly the worst investment we could make.

Faced with an unprecedented economic recession and high unemployment, we do need economic stimulus and job creation. Infrastructure investment should — and likely will – be part of the next government budget. But instead of investing in industries like aviation, with low job-creation potential and high carbon emissions, we should be investing in green infrastructure and green jobs. At NEF we’ve found, for instance, that there is huge job creation and fiscal stimulus potential if we invest in upgrading and decarbonising homes.

Regardless of the size of our airports and the speed at which the sector decarbonises, job numbers in aviation are likely to fall. Rather than expanding airport capacity we should be seizing the opportunity presented by the government’s furlough scheme and supporting aviation workers to access new green jobs – upskilling and retraining under-used employees for careers in low-carbon industries.

Image: Pexels