Few doubt that the mid-fourteenth-century Afro-Eurasian plague pandemic, the Black Death, killed tens of millions of people. In western Asia and Europe, where its spread and mortality are best understood, upwards of 50% of the population is thought to have died within approximately 5 years. …The regionality of the plague’s mortality is particularly underexplored, owing to the availability of written sources and the limits of traditional historical methods. Here we pioneer a new approach, big data palaeoecology (BDP), that leverages the field of palynology to evaluate the demographic impact of the Black Death on a regional scale across Europe, independent of written sources and traditional archaeological material. Our analysis of 1,634 pollen samples from 261 sites, reflecting landscape

Topics:

Chris Blattman considers the following as important: biology, disease, Europe, plague, Research, science

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Asad Zaman writes Newton’s lost revolution: Why his most radical work remains unread

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Debunking mathematical economics

Few doubt that the mid-fourteenth-century Afro-Eurasian plague pandemic, the Black Death, killed tens of millions of people. In western Asia and Europe, where its spread and mortality are best understood, upwards of 50% of the population is thought to have died within approximately 5 years.

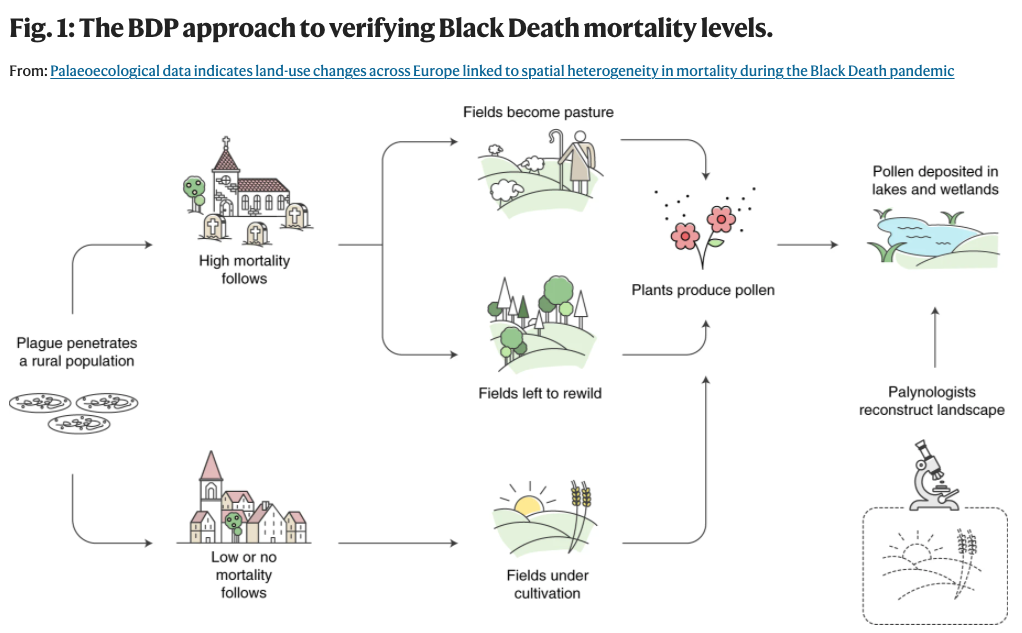

…The regionality of the plague’s mortality is particularly underexplored, owing to the availability of written sources and the limits of traditional historical methods. Here we pioneer a new approach, big data palaeoecology (BDP), that leverages the field of palynology to evaluate the demographic impact of the Black Death on a regional scale across Europe, independent of written sources and traditional archaeological material.

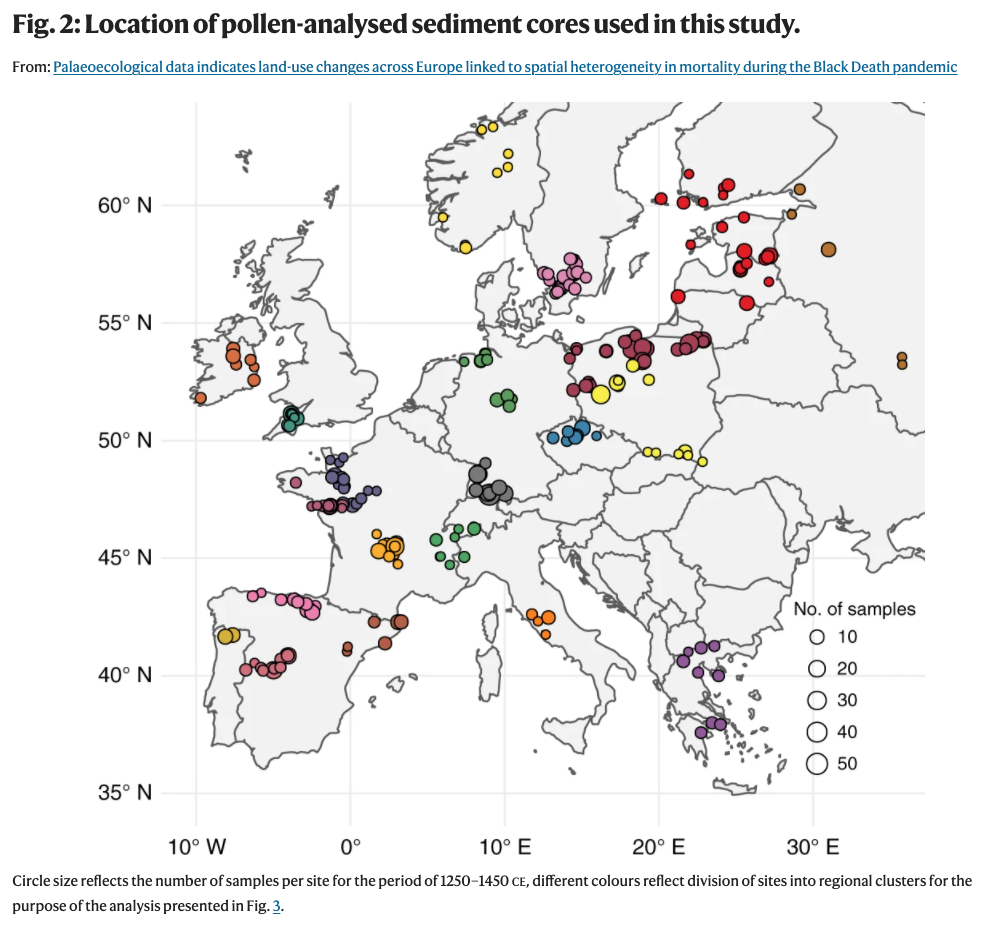

Our analysis of 1,634 pollen samples from 261 sites, reflecting landscape change and agricultural activities, demonstrates Black Death mortality was far more spatially heterogeneous than previously recognized. Strikingly, BDP provides independent confirmation of the devastating toll of the Black Death reflected in written sources in some European regions, while establishing conclusively that the Black Death did not affect all regions equally.

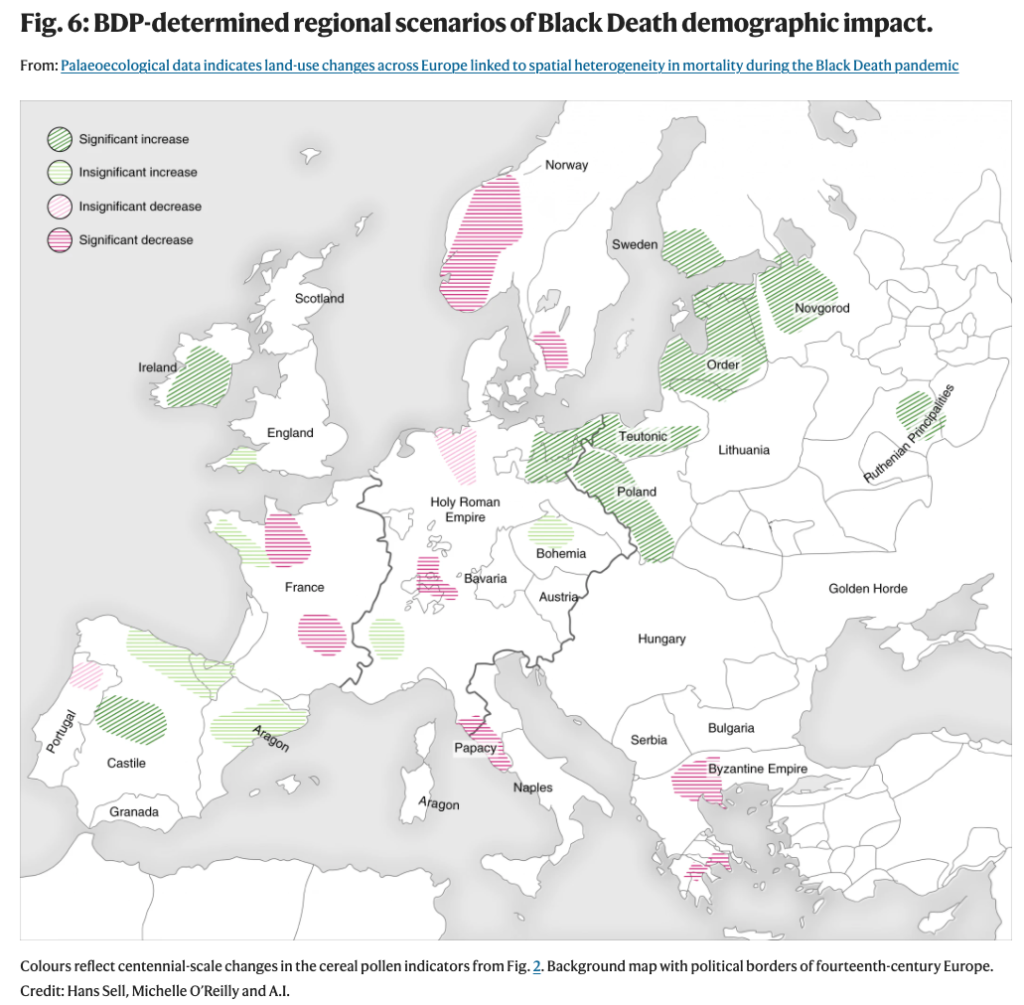

Figure 6 visualizes the spatial distribution of the four trajectories of post-Black Death landscape change from Fig. 4, demonstrating that the Black Death’s mortality varied significantly between European regions. The pandemic was immensely destructive in some areas, but in others it had a far lighter touch. Strikingly, BDP identifies a sharp agricultural decline in several regions of Europe, independently corroborating analyses of historical sources that suggest high mortality in regions of Scandinavia, France, western Germany, Greece and central Italy, and lending further validation to our approach. At the same time, there is much evidence for continuity and uninterrupted agricultural growth in central and eastern Europe, and several regions of western Europe, particularly in Ireland and Iberia. In this way, BDP invalidates histories of the Black Death that assume Y. pestis was uniformly prevalent, or nearly so, across Europe and that the pandemic had a devastating demographic impact everywhere.

That is from Izdebski and dozens of coauthors writing in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

There were many causes, but this one is particularly interesting:

Cereal trade is thought to have been instrumental for the introduction of the pandemic to Mediterranean Europe, and along established conduits of commerce and communication, ecological factors, associated contingency effects and historical path dependency mattered from the outset. Before the pandemic arrived in the Crimea, the volume of cereal trade between Italy and the Black Sea was sizable, yet blocked by embargo. High demand in southern Europe for Black Sea cereals from 1345 onwards was associated with a period of excessive precipitation and cooling negatively affecting cereal supplies in Italy and beyond. Cereal imports from Black Sea coasts resumed once the situation improved in 1347, and by early 1348 Venetian merchants had filled many Italian granaries with Black Sea produce and introduced plague to Europe. Plague outbreaks disseminated from major cereal ports in southern and north-western Italy from January 1348. To the contrary, plague hardly spread in north-western Italy, which was independent from overseas cereal imports.