Blog A New Year’s Resolution for our politicians? Rethinking government debt and borrowing rules We can't have a healthy climate or thriving public services without rethinking our fiscal rules By Dominic Caddick 03 January 2024 As we enter 2024, we begin the season of setting new rules and resolutions for our lives. We also enter the biggest election year in history, including major elections in the EU and UK. If politicians vying for parliamentary power are looking for a new year’s resolution, they should commit to loosening up government debt

Topics:

New Economics Foundation considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

A New Year’s Resolution for our politicians? Rethinking government debt and borrowing rules

We can't have a healthy climate or thriving public services without rethinking our fiscal rules

03 January 2024

As we enter 2024, we begin the season of setting new rules and resolutions for our lives. We also enter the biggest election year in history, including major elections in the EU and UK. If politicians vying for parliamentary power are looking for a new year’s resolution, they should commit to loosening up government debt and borrowing rules.

Self-imposed limits on how much debt governments can owe and how much they can borrow are common across many economies. These “fiscal rules” are supposed to be in place to protect us from spiralling borrowing costs and defaulting on our debt, which can hurt a country’s financial stability, political credibility and relations with other nations. But from the UK to the EU, these rules are set at unnecessarily harsh levels, restricting our ability to invest to tackle the climate crisis and protect public services like schools and hospitals.

In the EU, countries have to limit their debt to 60% of their gross domestic product (GDP) and their yearly borrowing (known as their “deficit”) to 3% of GDP. But during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, these limits were temporarily suspended and now the average EU country has debt at 83.1% and a deficit of 3.3% with no clear risk of default or spiralling costs. Being guided by such arbitrary values is irresponsible, yet is commonplace across economies and is putting climate targets and public services in jeopardy.

In last month’s autumn statement, Jeremy Hunt cut taxes, boasting his “fiscal headroom” had doubled since March. Fiscal headroom measures how much additional spending a government could make before breaking their debt and borrowing rules. However, this headroom is still low by historical standards meaning our fiscal rules are tighter than usual. To satisfy these rules, all new government spending or tax cuts must come with spending cuts or tax rises elsewhere. Hunt’s tax cuts were effectively funded by cuts to vital public services like transport, courts and local councils. Yet after a decade of cuts these services are already stripped to the bone, and it is hard to see how much more they can take. By design these cuts will hurt most in the future, kicking the can down the road for the next government to deal with evermore underfunded public services.

“… these rules are set at unnecessarily harsh levels, restricting our ability to invest to tackle the climate crisis and protect public services like schools and hospitals.”

This government’s fiscal rules have inbuilt weaknesses that lead to such decisions. First, the rules on debt and borrowing only cap spending and do not safeguard against underspending on public services. Second, the rules are reliant on forecasts five years into the future but these forecasts are often inaccurate, meaning the headroom measure can be very volatile. Before last year’s autumn budget, estimates of government finances ranged from a “fiscal hole” of £27bn to headroom of £32bn. Lastly, these economic forecasts can bake in austerity when they automatically adjust tax revenues for new economic conditions but do not do the same for spending on public services. This becomes a problem, like at the latest budget, when inflation improves tax revenue forecasts due to higher take from profits and sales taxes but leaves public services losing out in real terms.

When it comes to the main opposition party, Labour has promised to invest £28bn a year from 2027 in a “green prosperity plan”. This massive investment could boost the UK economy and create thousands of quality jobs, while kicking the UK’s addiction to expensive fossil fuels. However, in an attempt to look fiscally responsible, Labour insist they won’t fund anything through borrowing if it doesn’t meet their fiscal rules. Labour have also avoided announcing plans for new tax rises, even on the very wealthiest, giving themselves no room to raise extra funds. If they stick to their climate plans, tax promises and borrowing rules, they will have to make government cuts elsewhere, to our already decimated public services.

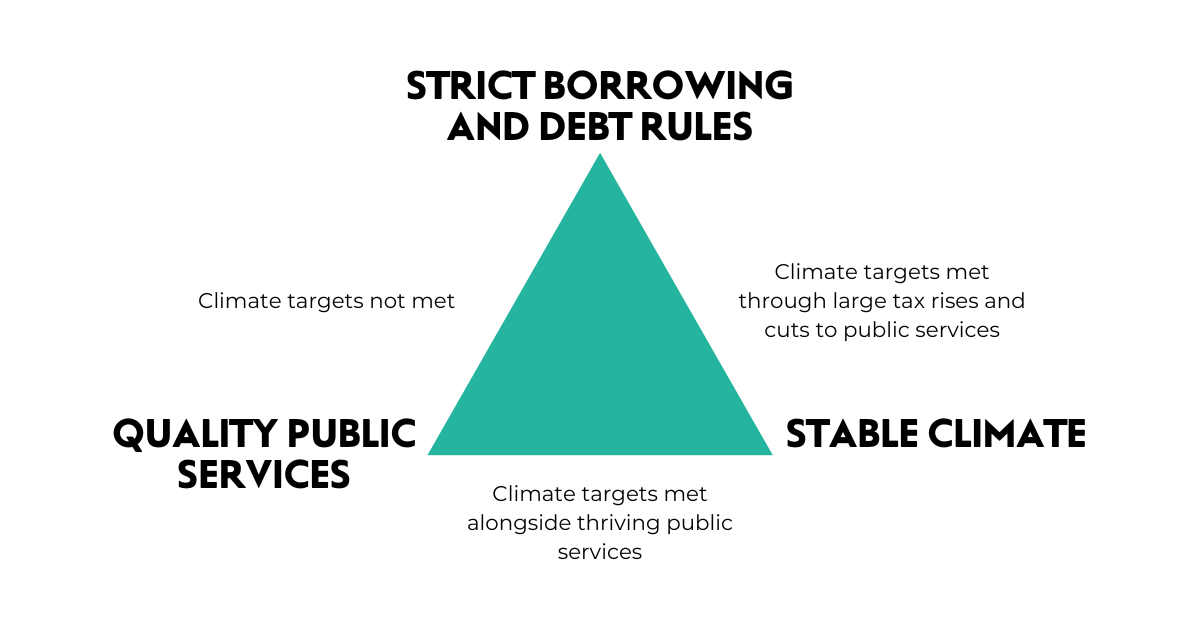

Both in the EU and the UK, public services have been cut to the bone, while the massive investment needed to meet climate targets is becoming more and more needed. At NEF we have found that only four EU countries will be able to borrow to meet their climate targets while sticking to EU borrowing rules. This brings us to an impossible choice: a stable climate, decent public services and arbitrarily strict debt and borrowing rules cannot all be met at once. Currently, politicians are sacrificing the stability of our climate for our threadbare public sector, risking the safety of us all. But there is an alternative if we want to avoid climate disaster and provide quality public services.

The impossible trinity of strict borrowing and debt rules, a green economy and thriving public services

Source: NEF illustration inspired by presentation by Jakob von Weizsäcker, State Minister of Finance of Saarland

By replacing arbitrary borrowing rules, we can have a thriving public sector and a safe climate. Borrowing and debt limits with no economic grounding must be replaced with indicators that actually warn against spiralling debt costs and risks of default, like high interest payments and poor returns on government investment. Austerity and climate inaction will cost all of us more in the long run – and this must be taken into account. The Office for Budget Responsibility already models how the climate crisis may cause fiscal risks – yet our current borrowing rules are too short-term to include this. As NEF has proposed in the past, a panel of independent advisors, known as “fiscal referees”, could guide us by providing estimates of when spending is too low to cut dangerous carbon emissions and provide essential public services, or too high to keep borrowing sustainable.

Our economic policies are being decided by politicians who are fixated on damaging, self-imposed rules on government debt and borrowing. Sticking to these fiscal rules traps us in constant environmental or public sector crisis, even both. While politicians clamour over “difficult decisions” the alternative is clear: relaxing borrowing rules so they respond to real signs of economic distress.

Image: iStock

Topics Macroeconomics Public services