Academic Agent’s video on Herbert Hoover is below:[embedded content]First of all, it is true that Hoover was not a strict liquidationist. He supported limited interventionism, and was – for his time – a type of corporatist Republican. But was Hoover an “interventionist” relative to the interventions that became commonplace in Western mixed economies after 1933 and certainly after 1945? The answer is: no, Hoover was relatively non-interventionist in relation to the mixed economies of the post-1945 period. Hoover himself rejected effective Keynesian economics, which was the key to escaping the Great Depression.What is wrong in this video?Let us break it down as follows:1. Hoover’s “high wage” policy Hoover’s “high wage” policy was largely limited to certain industrial markets, and was not

Topics:

Lord Keynes considers the following as important: Academic Agent on Herbert Hoover: A Critique

This could be interesting, too:

First of all, it is true that Hoover was not a strict liquidationist. He supported limited interventionism, and was – for his time – a type of corporatist Republican. But was Hoover an “interventionist” relative to the interventions that became commonplace in Western mixed economies after 1933 and certainly after 1945? The answer is: no, Hoover was relatively non-interventionist in relation to the mixed economies of the post-1945 period. Hoover himself rejected effective Keynesian economics, which was the key to escaping the Great Depression.

What is wrong in this video?

Let us break it down as follows:

1. Hoover’s “high wage” policy

Hoover’s “high wage” policy was largely limited to certain industrial markets, and was not generally forced on industrialists, contrary to libertarian myths. Academic Agent (citing Rothbard) is wrong. Most of the industrialists of Hoover’s day agreed with his high wage policy.

The proof can be seen below.

On November 21 1929, Hoover met with business leaders and labor representatives in the White House. The press release makes interesting reading:

“The conference this morning of 22 industrial and business leaders warmly endorsed the President’s statement of last Saturday as to steps to be taken in the progress of business and the maintenance of employment. The general situation was thoroughly canvassed, and it was the unanimous opinion of the conference that there was no reason why business should not be carried on as usual; that construction work should be expanded in every prudent direction both public and private so as to cover any slack of unemployment. It was found that a preliminary examination of a number of industries indicated that construction activities can in 1930 be expanded even over 1929. ….So the “high wage” policy was not some alien, evil government intervention imposed on unwilling and hostile business people and industrialists: it was a policy they largely agreed with.It was considered that the absorption of capital in loans on the stock market had postponed much construction and that the flow of this capital back to industry and commerce would now assist renewed construction.

It was the opinion that an indirect but very substantial contribution could be made to the extension of credit for local building purposes and for conduct of smaller business if the banks would freely avail themselves of the rediscount privilege offered by the Federal Reserve Banks.

The meeting considered it was desirable that some definite organization should be established under a committee representing the different industries and sections of the business community, which would undertake to follow up the President’s program in the different industries.

It was considered that the development of cooperative spirit and responsibility in the American business world was such that the business of the country itself could and should assume the responsibility for the mobilization of the industrial and commercial agencies to those ends and to cooperate with the governmental agencies. ….

The President was authorized by the employers who were present at this morning’s conference to state on their individual behalf that they will not initiate any movement for wage reduction, and it was their strong recommendation that this attitude should be pursued by the country as a whole. They considered that aside from the human considerations involved, the consuming power of the country will thereby be maintained.

The President was also authorized by the representatives of labor to state that in their individual views and as their strong recommendation to the country as a whole, that no movement beyond those already in negotiation should be initiated for increase of wages, and that every cooperation should be given by labor to industry in the handling of its problems.”

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=22009

Vedder and Galloway (1997: 92) – who themselves think that the high wages were the major cause of the unemployment during the depression – nevertheless point out that Hoover received “wholehearted support” from businessmen at his White House meeting on November 21, 1929. Even Henry Ford agreed with it (Vedder and Galloway 1997: 92).

Furthermore, even though there was some degree of “jawboning” of certain business people who wished to cut wages,

“In a survey of business leaders in mid-1930 by Printer’s Ink magazine, corporate executives were near-unanimous in their support of the high-wage policy coming out of the November 1929 conference at the White House. Howard Heinz, the ketchup maker, said: ‘In this enlightened age, large manufacturers . . . will maintain wages ... as being the far-sighted and . . . the constructive thing to do.’ Carleton Palmer, president of E. R. Squibb & Son, advocated increasing hourly wages by reducing the workweek and maintaining weekly wages constant. William Wrigley, the gum magnate, said he would not reduce wages, while Charles C. Small, president of the American Ice Co., said he believed in ‘good wages to aid purchasing power.’ George F. Johnson, president of Endicott Johnson Corp., echoed that sentiment, declaring that ‘reducing income of labor is not a remedy for business depression; it is a direct and contributing cause.’Now let us assume for the sake of argument that the “high wage” policy really was the single worst policy endorsed by Hoover. But why aren’t Austrians blaming the private industrialists and business people who supported and endorsed this “high wage” policy, since it was clearly their fault as much as Hoover’s? It is doubtful that the “high wage” policy could have been carried out without so much support from the private sector: in fact, very many corporate leaders already held the same opinion as Hoover.Big business felt it had a duty to carry through the high-wage-policy.” (Vedder and Galloway 1997: 94)

Secondly, Gardiner Means, in his own contemporary work on prices in the 1920s and 1930s, noted how it was in fact industrial prices that had already become relatively less flexible than other prices in the US economy during the early years of the Great Depression (Lee 1998: 28).

So, given that relative inflexibility in industrial prices, to what extent did the high wages per se with (less severe) price cuts in those industries really exacerbate the depression? Although it stands to reason that, when industrial prices did start to fall significantly, this would have squeezed profits in the relevant industries, the fact is that output and employment was already directly reduced in many firms anyway as a response to the demand shocks, which were the primary cause of the increased unemployment.

Most important of all, far from being the solution to the depression, severe wage cuts even in 1929 would have severely worsened the debt deflationary spiral and increased the real burden of debt for debtors, putting pressure on them and eventually driving many into bankruptcy, and in turn driving creditors into bankruptcy. Of course, that is exactly would did happen in the depression as nominal wages fell after 1931 and continued to fall in 1932 and 1933.

Moreover, as is now well known, the extent of nominal wage flexibility in the West before 1929 is grossly exaggerated. In reality, wages had already started to become relatively inflexible downwards in recessions after the late 1880s, as can be seen here. It is a complete myth that US recessions were cured by flexible wages, because there were numerous recessions after the 1880s where this was not the case.

2. Comparing the Recession of 1920–1921 with the Great Depression

Academic Agent compares the money wage falls in the recession of 1920–1921 with the less flexible money wage data in the early years of the Great Depression (whose contractionary phase ran from 1929 to 1933).

Unfortunately, the recession of 1920–1921 was highly anomalous, coming as it did after the First World War and the extensive wartime inflation which eroded the value of private debt, and cannot be usefully compared with the situation in 1929–1933, as I have shown here. In short, in 1929–1933 wage and price deflation caused a severe debt deflationary spiral, which was avoided in 1920–1921, because of the different conditions then.

And, of course, libertarians like Academic Agent cannot explain why severe wage and price deflation in Weimar Germany or in Austria in the 1930s did not lead to a rapid recovery there.

3. The Smoot Hawley Tariff

Academic Agent makes much of the Smoot Hawley Tariff and argues that it was a “massive” cause of the depression, and even that it was the major cause. This is a blatant falsehood, contrary to the data we have.

The Tariff Act of 1930 (or Smoot–Hawley Tariff) became law on June 17, 1930. While Smoot Hawley undoubtedly hurt foreign export-led growth nations dependent on the US market, it was not a major factor in the US contraction from 1929–1933.

Peter Temin explains:

A tariff, like a devaluation, is an expansionary policy. It diverts demand from foreign to home producers. It may thereby create inefficiencies, but this is a second-order effect. The Smoot-Hawley tariff also may have hurt countries that exported to the United States. The popular argument, however, is that the tariff caused the American Depression. The argument has to be that the tariff reduced the demand for American exports by inducing retaliatory foreign tariffs … Exports were 7 percent of GNP in 1929. They fell by 1.5 percent of 1929 GNP in the next two years. Given the fall in world demand in these years from the causes described here, not all of this fall can be ascribed to retaliation from the Smoot-Hawley tariff. Even if it is, real GNP fell over 15 percent in these same years. With any reasonable multiplier, the fall in export demand can only be a small part of the story. And it needs to be offset by the rise in domestic demand from the tariff. Any net contractionary effect of the tariff was small (Temin 1989: 46).America was not an export-led economy in the 1920s and 1930s, and export growth was not the primary engine of American growth at all. As noted by Temin, exports were just 7% of US GNP in 1929.

Contrary to Academic Agent, it is a complete myth that the United States suddenly faced economic collapse because foreign companies suddenly left and closed factories in America after Smoot Hawley.

Worse still for Academic Agent, the Smoot Hawley Tariff was not some exception in American history. The United States had a long history of high tariffs, as can be seen here. In fact, the average level of duties on manufactured goods in 1875 in the United States was about 40–50%, and the Republicans in September 1922 had returned to a high tariff policy with the Fordney–McCumber Tariff, which raised the ad valorem tariff rate to an average of about 38.5% for dutiable imports, which was years before the Great Depression even happened (Bairoch 1993: 38).

Why, then, didn’t the Fordney–McCumber Tariff of 1922 crash the US economy if high tariffs had such a bad effect?

Nor, contrary to Academic Agent, was the Smoot Hawley tariff or the collapse in agricultural production the primary cause of the banking failures in the US Great Depression. Those were caused largely by rapid insolvency of banks and then the large-scale bank runs triggered by panic.

The severe worsening of the depression in America was caused to a great extent by the banking panic of 1930 from November 1930 to August 1931, which could have been easily halted by Federal Reserve actions to protect depositors while liquidating bad debts.

4. Hoover’s Spending

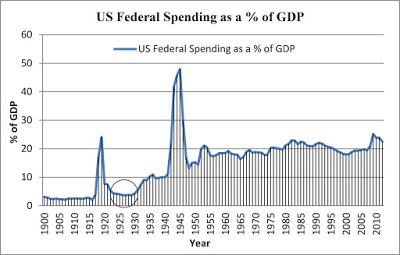

Hoover did not in fact massively increase government spending. Total US federal government spending in 1929 was about 2.5% of GDP (Stein 1966), and the rise in US federal government spending as a percentage of GDP from 1929 to 1933 was partly the result of the collapse in GDP, and not huge increases in government spending relative to GDP.

Given that US GDP collapsed by 28.52% between 1929 to 1933, the rise in US spending under Hoover was feeble and far short of what was need to stabilise GDP and end the depression.

We can see in this graph the absurdity of saying that Hoover massively increased government spending (with the circle showing the size of government spending in the 1920s to about 1933):

If huge government spending was a serious cause of depression, then why didn’t the US collapse after 1945 given the huge levels of spending that now occurred relative to the pre-1929 period?

.

Finally, let consider Hoover’s fiscal policy. Hoover’s fiscal policy in fiscal years 1930 and fiscal year 1933 was actually contractionary:

(1) In fiscal year 1930 (July 1, 1929–June 30, 1930), Hoover actually ran a federal budget surplus, not a deficit. Federal policy was contractionary in this fiscal year.These were contractionary measures, and these policies are the very antithesis of Keynesianism stimulus.(2) In fiscal years 1931 and 1932, fiscal policy was mildly expansionary, but feeble compared to what was needed.

(3) The Federal Reserve raised the discount rate in 1931.

(4) In fiscal year 1933 (July 1, 1932–June 30, 1933), total federal spending was cut in relation to fiscal year 1932. Hoover introduced the Revenue Act of 1932 (June 6) which increased taxes across the board and applied to fiscal year 1932 and subsequent years.

5. Other Interventions

Most of the other interventions Academic Agent lists were taken in 1932 and cannot possibly explain the severity of the depression from 1929–1931, with one exception: the Revenue Act of 1932 (June 6) which increased taxes.

However, Academic Agent is blissfully unaware that blaming this measure for exacerbating the depression (which is no doubt did do) is nothing but a vindication of Keynesian theory, which does not advocate raising taxes in recessions or depressions.

Finally, let us consider here the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). Blaming the RFC as some evil government intervention that made the depression worse is absurd. Why? Because the RFC was only established in January 1932, and it did not even exist in 1929, 1930 and 1931 when the US economy was collapsing badly. In 1932, the RFC spent about $1.5 billion in loans to states and businesses, and there are very good reasons for thinking that this policy per se would have aided the economy, not exacerbated the depression. But of course whatever good the RFC did was destroyed by Hoover’s contractionary fiscal policy in fiscal year 1933 – the exact opposite of a Keynesian policy response.

6. Counterexamples where Keynesian interventions worked

I have yet to see any libertarian explain why government interventions and Keynesian stimulus rapidly ended the Great Depression in a number of nations in the 1930s.

For we must ask the question: what nations emerged quickly from the Great Depression to have a strong recovery where unemployment fell to low levels?

Those nations that recovered rapidly and successfully from the Great Depression were New Zealand, Germany and Japan. They did so by large-scale fiscal stimulus and numerous other intervention far more extreme than what Hoover did.

More on the Keynesian policies in New Zealand, Germany and Japan is given in these posts:

“Keynesian Stimulus in New Zealand: 1936–1938,” September 23, 2011.It is also notable that some Scandinavian nations also left the gold standard quickly, devalued their currencies, stabilised their banking systems, implemented loose monetary policy, and perhaps some degree of fiscal stimulus to escape the worst ravages of the depression (although the question whether the Scandinavian countries pursued fiscal expansion and how strongly is disputed by some economists).“Takahashi Korekiyo and Fiscal Stimulus in Japan in the 1930s,” August 27, 2011.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bairoch, P. 1993. Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2000. Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Keynes, J. M. 1939. “Relative Movements of Real Wages and Output,” Economic Journal 49: 34–51.

Lavoie, Marc. 1992. Foundations of Post-Keynesian Economic Analysis. Edward Elgar Publishing, Aldershot, UK.

Lee, Frederic S. 1998. Post Keynesian Price Theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York.

Stein, H. 1966. “Pre-Revolutionary Fiscal Policy: The Regime of Herbert Hoover,” Journal of Law and Economics 9: 189–223.

Temin, P. 1989. Lessons from the Great Depression. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Vedder, Richard K. and Lowell E. Galloway. 1997. Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America. New York University Press, New York.