Could we possibly have a reasoned debate about the several alternative retirement schemes? To judge from the government’s attitude, one might well doubt it. The current government is endeavouring to restrict the discussion to the following schema: either you support my project (which remains extremely vague) or you are an old-time defender of the privileges of the past and refuse any change. The problem with this binary approach is that in reality there are many ways of constructing a universal retirement scheme, depending on whether the focus is on social justice and the reduction of inequalities ranging from the « common pension system » (« maison commune des régimes de retraite ») long defended by the CGT (General Confederation of Labout) to the project presented in the Delevoye

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english, Non classé

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

Could we possibly have a reasoned debate about the several alternative retirement schemes? To judge from the government’s attitude, one might well doubt it. The current government is endeavouring to restrict the discussion to the following schema: either you support my project (which remains extremely vague) or you are an old-time defender of the privileges of the past and refuse any change.

The problem with this binary approach is that in reality there are many ways of constructing a universal retirement scheme, depending on whether the focus is on social justice and the reduction of inequalities ranging from the « common pension system » (« maison commune des régimes de retraite ») long defended by the CGT (General Confederation of Labout) to the project presented in the Delevoye Report. In 2008, Antoine Bozio and I published a short book outlining possible paths for unification of the schemes. This publication had a number of limits and the discussions which ensued enabled me to clarify several basic points.

In particular, this book referred to several possible solutions in order to take into consideration the social inequality of life expectancy: either directly on the basis of the length of life observed by profession (for example, to correct the fact that a specific category of worker spent on average 10 years in retirement, as compared with 20 years for a specific category of executive); either in indirect or approximate fashion by structurally increasing the rates of contribution applied to the highest salaries, which on average benefitted from longer retirements, by raising the level of pensions open to the lowest salaries, which on average have shorter retirements.

The book merely listed these solutions, without clearly taking a position, with the risk that the question would be eluded, which is the case in the project of the present government.

On reflection, the direct method seems to me to be impracticable. It is better to clearly assume the indirect method, by introducing into the calculation of pensions more favourable treatment for low and medium salaries as compared with high salaries to correct the differences in life expectancy. This is not a perfect solution to a complex problem (these differences are determined by many other factors besides the level of salary, whence the need to also take into consideration the difficulty of certain professions), but it is nevertheless more satisfactory than the traditional solution, which consists in stating that the problem is enormous and complex, then doing nothing substantial to deal with it.

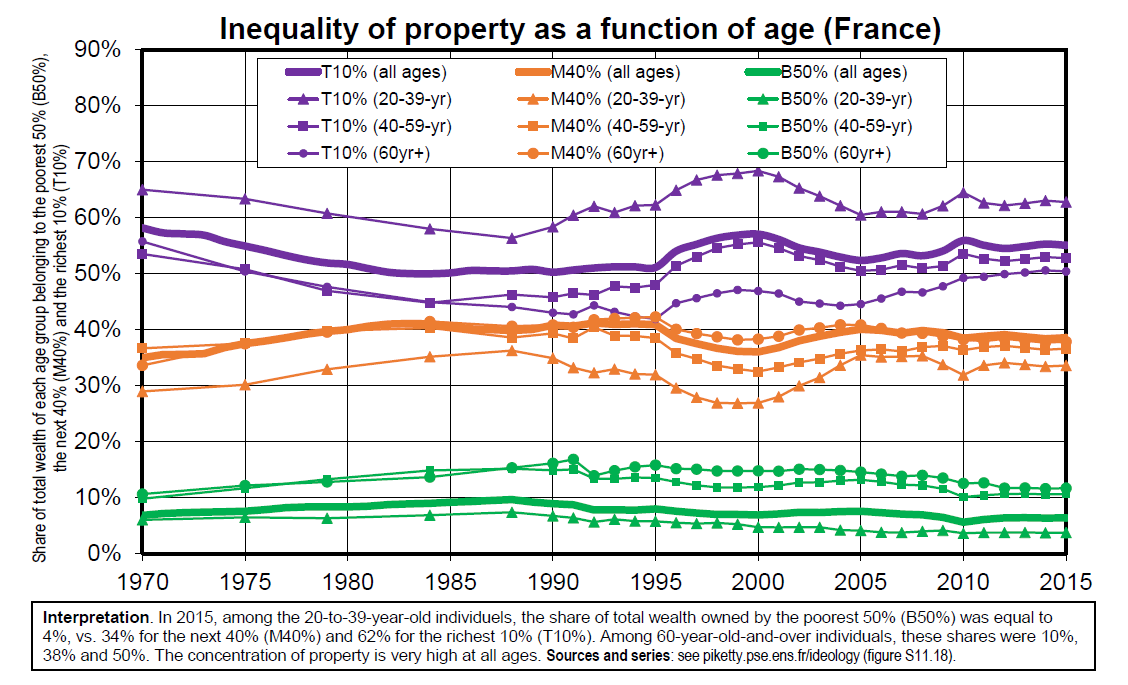

More generally, beyond the question of life expectancy, the old idea according to which the retirement system is only there to perpetuate into advanced old age the inequalities of working life does seem to me today to be outdated. Given the increasing inequality on the labour market (piece work for some, super-salaries for others), and the new human and social challenges posed by the high dependency of an aging population, it is time to take a more redistributive view of pension schemes. In material terms, we have to do our utmost to guarantee and to improve the lowest pensions (between 1 and 3 times the minimum wage) even if it means requesting a bigger effort from very high salaries and the very wealthy.

It is, after all, the absence of ambition in terms of social justice which poses a problem in the government’s project, as is the case elsewhere in the totality of its action. An attempt is being made to get low wage earners in the public sector to oppose low wage earners in the private sector when in both cases their incomes are modest when compared with those who have benefited from the fiscal generosity from the start of the government (abolition of the wealth tax, flat tax). Now, it is time to imagine a universal scheme which would be much more just in social terms, which would be in line with the ideas of the CGT on the “common pension system”.

For example, the Delevoye project envisages a pension equal to 85% of the minimum wage (the SMIC) for a complete career (43 years of contributions) at this level. Then the replacement rate falls suddenly to only 70% at the level of 1.5 times the minimum wage, before stabilising at this precise level of 70% until 7 times the minimum wage (120,000 Euros gross annual salary). This is one possible choice, but there are others. One could imagine that the replacement rate falls from 85% at the level of the minimum wage to 80% at 2 times the minimum wage, 75% at 3 times the minimum wage, before gradually declining toward 50% around 7 times the minimum wage. One could also choose to close the gaps in standard of living even further at retirement.

In any event, it is essential that the new universal scheme operates on ‘defined benefits’, that is to say with retirement benefits defined in advance in terms of the replacement rate applicable to the different levels of salaries, and not on a system of points. The latter can lead to concealing major cuts in the future, as witness the freezing of the point in the civil service for the past 10 years. The system of accounts in Euros which we had imagined in our book in 2008 to get away from the approach in terms of points is, in the end, less transparent and more anxiety-provoking that that of defined benefits.

Finally, the financing of universal retirement pensions must be based on solidarity and involve the participation of everyone and, in particular, the wealthiest. It must at least be made clear that a contribution rate of 28% applies to all wage-earners, including the highest, instead of falling to 2.8% on the salary bracket above 120,000 Euros, as stated in the Delevoye Report. One could also imagine a progressive scale with a greater engagement from the highest incomes and the wealthiest, particularly as the inequalities in wealth are high in our society, both amongst the oldest and the wage-earners. Several retirement schemes are possible: it is time to seize the opportunity for public discussion.