I wrote this for a Guardian panel. The published version was cut for space reasons, so here’s the full version The central concern expressed by the Reserve Bank in defending its high-interest rate policy is that expectations of higher inflation may become entrenched, requiring a further, more painful round of contractionary monetary policy in the future. Even after stripping out the effects of various “cost of living measures”, the RBA’s estimated core inflation rate is only just above 3 per cent. This suggests extreme sensitivity to the risk of even a modest increase in the long run rate of inflation. By contrast, the RBA expresses no concern that the reduction in economic growth induced by its policies will lead to a permanent reduction in living standards. The underlying

Topics:

John Quiggin considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

I wrote this for a Guardian panel. The published version was cut for space reasons, so here’s the full version

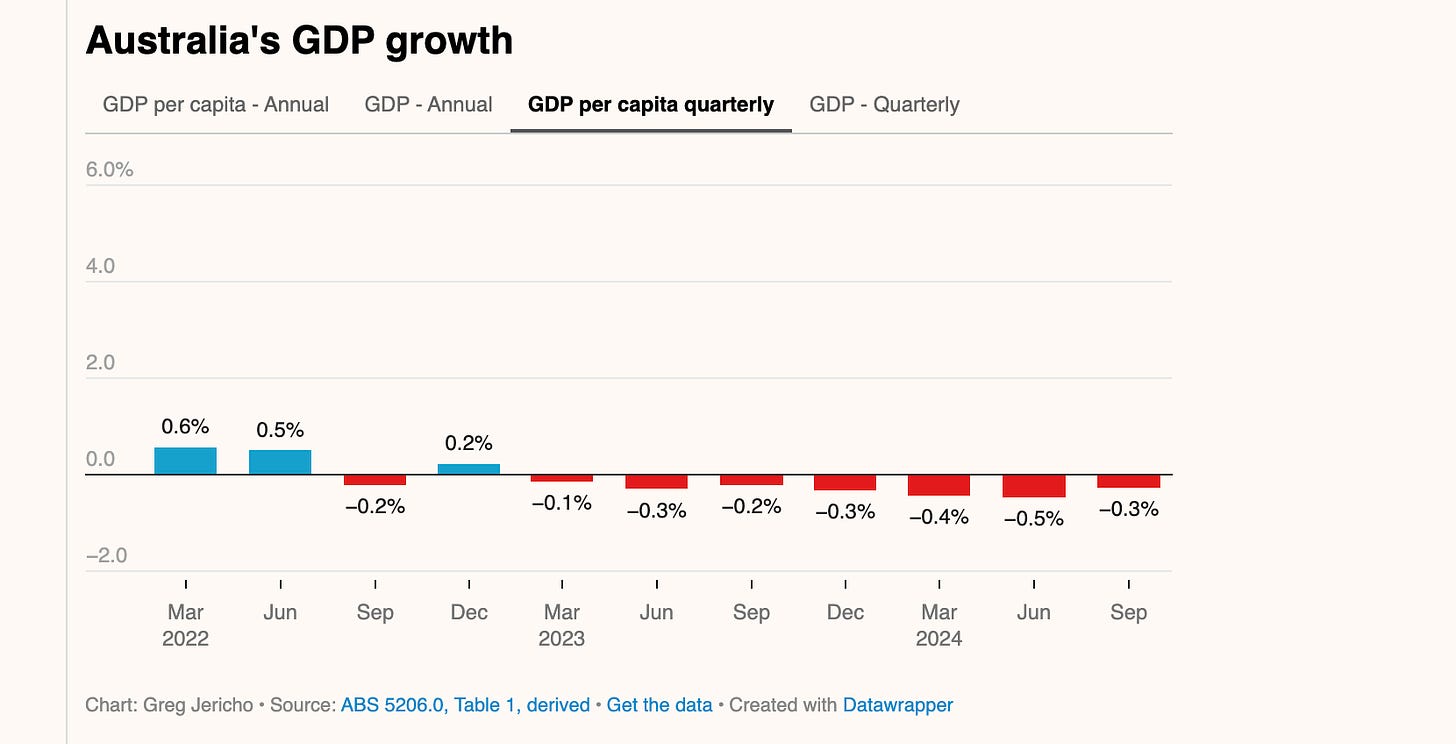

The central concern expressed by the Reserve Bank in defending its high-interest rate policy is that expectations of higher inflation may become entrenched, requiring a further, more painful round of contractionary monetary policy in the future. Even after stripping out the effects of various “cost of living measures”, the RBA’s estimated core inflation rate is only just above 3 per cent. This suggests extreme sensitivity to the risk of even a modest increase in the long run rate of inflation.

By contrast, the RBA expresses no concern that the reduction in economic growth induced by its policies will lead to a permanent reduction in living standards. The underlying assumption of the RBA’s macroeconomic model is that the economy will always return to a long-run growth path determined by technology and economic structure.

But there is ample evidence, notably from New Zealand and the UK to suggest that the loss in productive capacity associated with slowdowns and recessions is permanent or very close to it. Until the 1980s, the New Zealand and Australian economies grew almost in parallel. But from the early 1990s, onwards, while Australia has avoided recession (at least on the widely-used measure of two quarters of negative growth) for more than thirty years, New Zealand has had at least half a dozen. This miserable performance, reflecting both policy misjudgements and overzealous neoliberal reforms has resulted in New Zealand falling far behind Australia in terms of incomes and living standards. The steady flow of New Zealanders to our shores, and the lack of any comparable flow in the opposite direction, reflects this.

In the UK, the combined effects of the GFC, Conservative austerity policies and Brexit has produced a long period of stagnation in national income. As Brad DeLong observes, had Britain continued on its pre-2008 growth trend it would now be forty percent richer than it is today

The Unmaking of a Modern Economy: Brexit, Austerity, and Britain’s Great Retraction

Even though Australia has experienced a lengthy period of declining national income per person, the RBA does not even mention the risk of a permanent reduction in living standards. In its pursuit of rapid achievement of an essentially arbitrary inflation target, RBA monetary policy puts all our futures at risk