Once again on the shadow playing of Greek capitalism Stavros Mavroudeas Professor of Political Economy Panteion University Diachronically, at the end of the year and with the parliamentary submission of the budget, it ‘rains’ with hypocritical publications where the incumbent government aggrandizes the economic situation. Accordingly, this year too, the right-wing New Democracy government is constructing a new ‘success story’ (as every previous government had done). And unsurprisingly similarly, the current ‘loyal opposition’ (center-left, pseudo -left and far-right) whines about secondary issues. No one touches on the core of the problems of the country and the people, which stem from the interests of the ruling class and the dictates of the European Union. More

Topics:

Stavros Mavroudeas considers the following as important: Greek capitalism, Mavroudeas, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Once again on the shadow playing of Greek capitalism

Stavros Mavroudeas

Professor of Political Economy

Panteion University

Diachronically, at the end of the year and with the parliamentary submission of the budget, it ‘rains’ with hypocritical publications where the incumbent government aggrandizes the economic situation. Accordingly, this year too, the right-wing New Democracy government is constructing a new ‘success story’ (as every previous government had done). And unsurprisingly similarly, the current ‘loyal opposition’ (center-left, pseudo -left and far-right) whines about secondary issues. No one touches on the core of the problems of the country and the people, which stem from the interests of the ruling class and the dictates of the European Union. More specifically, nowadays every systemic political party has become a fun of the EU-IMF economic austerity programmes for Greece and the subsequent supposedly ‘benevolent’ role of the EU; and they simply jockey about which of them is their best enforcer.

After fourteen years of harsh capitalist restructuring on the backs of workers some short-term macroeconomic figures have improved. This has been echoed by some rather curious (?) international publications (e.g. FT’s ‘The astonishing success of Eurozone bailouts’). The main arguments of all these mainstream ‘beauticians’ are the following.

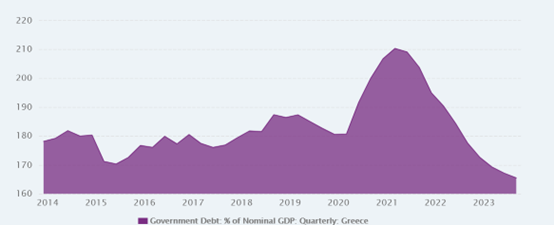

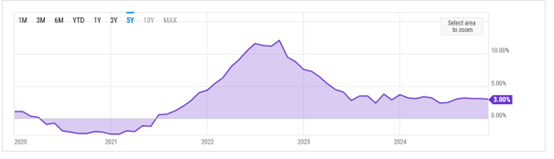

The first argument is that there is a reduction of the debt/GDP ratio and a fall in borrowing costs. The reduction of the debt/GDP ration is mainly caused by the high inflation that inflates the denominator. Only a smaller partial reduction is caused by the (a) the high primary surpluses that choke the Greek economy, (b) the premature repayment of a more expensive part of the debt and (c) the increased taxation (again caused by the inflationary increase in incomes and consumption prices).

Debt to GDP ratio

On the other hand, the total amount of foreign debt remains high.

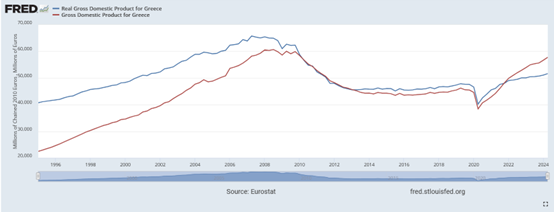

The Greek GDP remains below the pre-crisis level.

The reduction of the borrowing costs has to do with ‘relative’ reasons. The viability of the Greek debt is guaranteed for the short-run period under the EU-IMF austerity programmes. Problems will emerge after 2032 when the repayment of debt will recommence. Additionally, the euro-core economies have been severely hit by imperialist conflicts and internal conflicts and increased their debt levels. Italy, and lately France, have come to the attention of so-called ‘debt-vigilantes’ and profiteers. Hence, in the short-run, Greek debt appears more secure. Moreover, the amounts that Greece is borrowing are small (given the size of the international market ), Greek banks (in cahoots with the government) can easily absorb much of them. Hence, borrowing costs are not convincing indicators of economic success.

The second argument – echoed again by FT articles – is that Greece (and the other PIGS) surpass the EU average growth rate and the growth rates of the euro-centre economies. If we take a more long-run view, we see that this superior performance has happened also during past periods, but it was not sustained for long. Thus, the structural rift between the euro-centre and the euro-periphery economies – irrespective of conjunctural variations – has persisted.

More concretely, the explanation for the recent overperformance of countries like Portugal, Greece, Spain (but also Croatia, Slovenia, and Austria) lays in the crisis of the backbone of the productive structure of the European Union. This is composed by the Northwestern powerhouse of strongly industrialised economies (Germany, Netherlands etc.). The eruption of the Ukrainian conflict led to a rapid increase of energy costs, amplified by the volatile nature of the European energy stock-exchange system. Moreover, the aggravation of global geopolitical tensions and conflicts (for example, the US (plus EU)-China trade war) have affected traditional global value chains on which EU’s economy was depending. Thus, the increase of energy costs is leading to a de-industrialisation of euro-centre economies. The sanctions’ game of the Western countries is increasingly disrupting established production and trade links. In contrast, less industrialised economies (like those of the euro-periphery) are affected less from the increase in energy costs. Additionally, they have the advantage of lower wages. Thus, there are signs of a relocation of productive and trade activities from the euro-centre to the euro-periphery by firms of the euro-centre economies. In simple words, German firms relocate and/or subcontract some of their activities to euro-periphery economies. Does this lead to a reduction of the rift between euro-centre and euro-periphery? It is very doubtful and very premature to confer an opinion on this. Such moves happened in the past, but they affected only marginally this rift. In any case, the commanding heights of the EU edifice remain always in the euro-centre economies irrespective of how they allocate their activities.

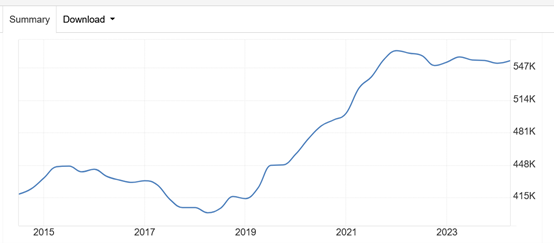

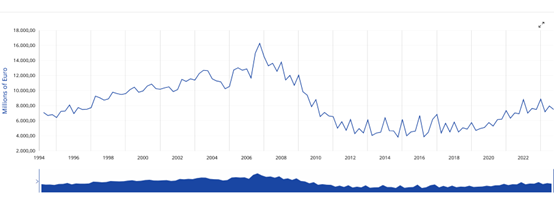

The third governmental argument is that there is an increase in investment. There is indeed a small increase in investment; although the gap between the existing and the required investment in order to cover the GDP reduction from the crisis is still huge. Behind the relative improvement in investment lies the bonus of the Resilience and Growth Fund. But the vast majority of investment goes to non-productive sectors (real estate, tourism, etc.) and crony deals with the government. This implies that it has limited inter-sectoral linkages and fails to become a growth booster in the long-run.

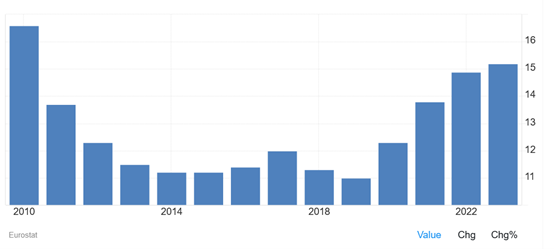

Gross fixed capital formation, Greece, Quarterly

Greece – Gross fixed capital formation as % of GDP

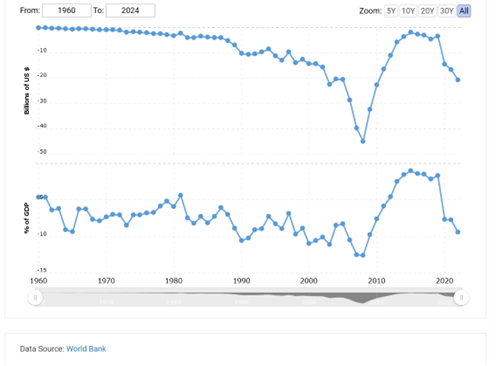

The fourth argument, that is somehow muted recently because of negative data, is that Greece is becoming an export economy. Again, FT has propagandised in the past this bogus claim. There is no Greek export miracle and there cannot be one. The two leading Greek export sectors are oil products and tourism. The former is a manufacturing activity and the latter a service one. Both depend crucially on imports. The oil industry for obvious reasons: Greece is not an oil-producing country. The tourist sector is notorious for its so-called ‘leakages’; that is the imports that are necessary for its operation, and which are quite expensive. There is an additional problem regarding the trade balance of the Greek economy. The majority of its sectors are medium technology and low value-added, depending critically upon the import of intermediate goods. Thus, every increase in GDP growth necessarily brings forth a deterioration of the trade balance and the current account. Thus, the very structure of the Greek productive model precludes the possibility of becoming an export economy.

Because of these structural characteristics the barbaric ‘internal devaluation’ – instigated by the IMF and the EU in cahoots with the Greek oligarchy – did not led to a significant increase in competitiveness. Moreover, Greek enterprises used the reduction in wages as a means to increase their profit margins instead of lowering their prices. For all these reasons, the reduction of wages did not transform Greece to an export-led economy, despite the IMF-EU-ECB troika declarations. The following graph is telling.

Greece Trade Balance 1960-2023

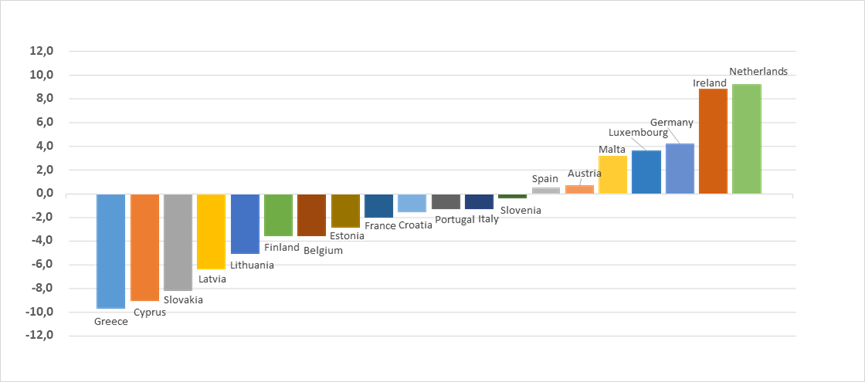

Government’s propaganda chooses to neglect the problem of the current account deficit, which is closely linked to the trade deficit. The import dependence of the Greek economy means that even a small increase in growth causes significant import increase, leading to a worsening of the trade deficit. The Greek economy recorded the highest current account deficit, i.e. -9.7% of nominal GDP, in 2022 relative to all other euro area countries, following an already very high deficit (-6.8% of GDP) in 2021.

Current account balance as a percentage (%) of GDP across euro area countries in 2022

Source: Statistics | Eurostat (europa.eu).

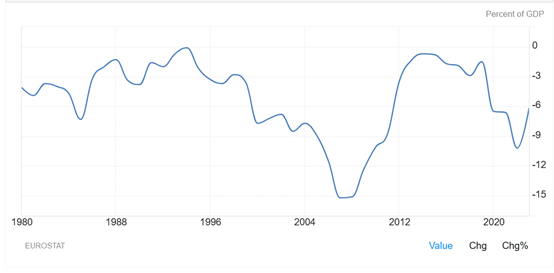

Greece Current Account to GDP

Leaving aside government’s propaganda, the majority of the Greek people suffer from worsening pay and working conditions and increasing inequality and poverty.

Greece is leading both in the reduction of real wages and in the increase in working hours).

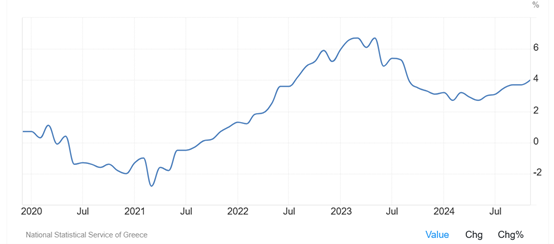

The reduction of real wages, in long run perspective, is caused by (a) the brutal ‘internal devaluation’ of the EU-IMF austerity programmes and (b) the galloping inflation of the last years.

Greece Inflation Rate

Greece Inflation Rate

Greece Core Inflation Rate

Thus, in terms of GDP per capita at purchasing power parities, Greece is the second-poorest country in the EU, surpassed even by all the former eastern bloc countries apart from Bulgaria. EUROSTAT calculated that over 26 per cent of the population is being at risk of poverty and social exclusion; putting Greece in the fourth place from the end within the EU.

Greek capital threw the country into the ‘lions’ den’ of the European unification, seeking to upgrade itself within the international imperialist pyramid. Instead, the country sank into the crises of 2008 and 2010 and was degraded. The EU-IMF capitalist restructuring programmes managed to overcome the crisis for capital on the backs of the workers; but the country continues to languish.

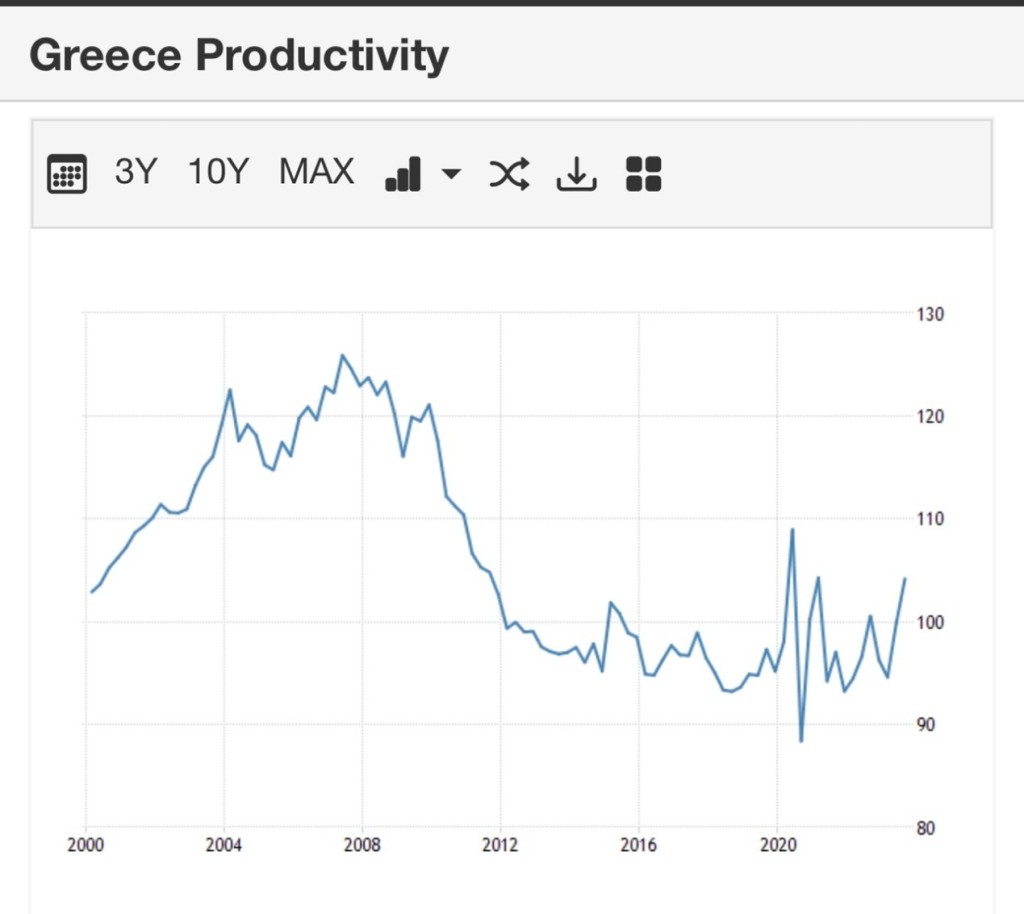

Capitalist profitability – despite the brutal exploitation of workers – is not recovering sufficiently. This is linked to the avoidance of productive investments and the resulting low labor productivity.

In addition, the structure of the economy (weak primary and secondary sectors, overblown tertiary sector, low technological level and low added value, high dependence on imported inputs, etc.) remains problematic.

The result is that Greek capitalism is teetering towards its next crisis. In the short term, the current account balance, in the long term (after 1932, the debt) but also in the long term, the short-sighted horizon of Greek capital and its problematic production model pave the way for it. Capital’s political administrators are simply biding their time and negotiating their electoral survival.

The only possibility for changing course is if the working people realize not only their miserable situation but also their power to change things.