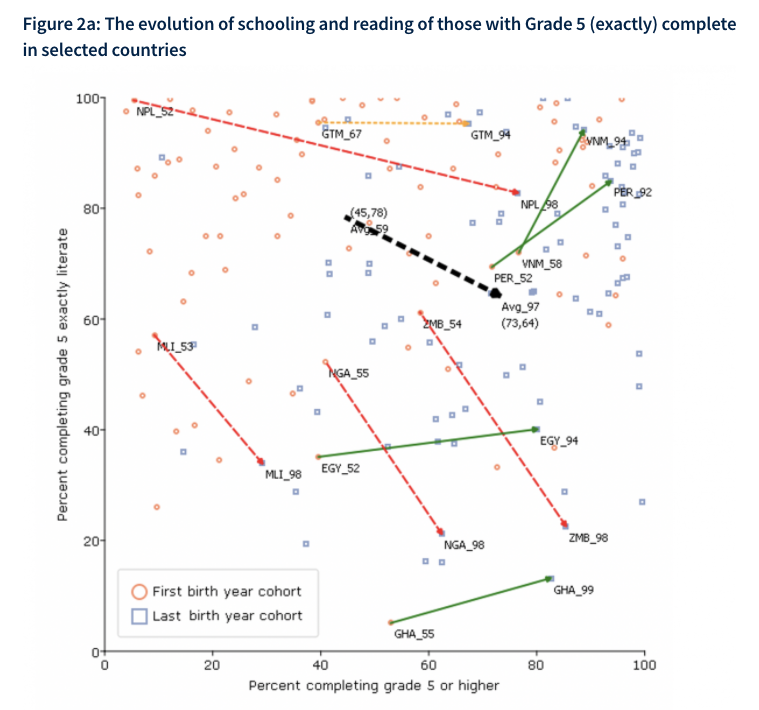

We use literacy tests in survey data to construct long-term trends in literacy for 87 developing countries, spanning birth cohorts from the 1950s to 2000. We show that over this period literacy rates have increased substantially, but virtually all progress has been due to the increase in access to school rather than any improvement school quality, which we define as the propensity for schooling to generate literacy after five years of schooling. Overall, school quality is low in developing countries with about 70% of women able to read after grade five and quality has been declining over time. From the 1950s to 2000, school quality deterioration implied the probability that a woman with five years of schooling could read a sentence fell by roughly two to four percentage points per decade

Topics:

Chris Blattman considers the following as important: Education, international, literacy, Research, schooling

This could be interesting, too:

Joel Eissenberg writes The Trump/Vance Administration seeks academic mediocrity

Bill Haskell writes Study Shows Workers Fleeing States With Abortion Bans

Angry Bear writes The Impact of Debt Interest Payments

Angry Bear writes Rust Belt Cities reborn?

We use literacy tests in survey data to construct long-term trends in literacy for 87 developing countries, spanning birth cohorts from the 1950s to 2000. We show that over this period literacy rates have increased substantially, but virtually all progress has been due to the increase in access to school rather than any improvement school quality, which we define as the propensity for schooling to generate literacy after five years of schooling.

Overall, school quality is low in developing countries with about 70% of women able to read after grade five and quality has been declining over time. From the 1950s to 2000, school quality deterioration implied the probability that a woman with five years of schooling could read a sentence fell by roughly two to four percentage points per decade and about six percentage points for men.

Although the negative trends in school quality is concerning, a more generous reading of the results is that most school systems have managed to dramatically expand their education offer without very large drops in school quality. Trends in school quality are relatively stable over time, and there are few if any identifiable cases of large and rapid improvements in school quality at the national level.

That’s from a new paper by Alexis Le Nestour, Laura Moscoviz, and Justin Sandefur, emphasis mine.

If I understand this correctly, the generous reading comes from the idea that a vast expansion of schooling implies that poorer and less able kids are being pulled into the system (along with the creation of new and presumably less capable schools) and so the learning outcomes of these kids are far better than they would have been otherwise. Schools skimmed the cream in the 1950s, and so the numbers look falsely promising.

In a blog post, Lant Pritchett discusses the paper and (proving he puts far more work into his posts than I do) uses their data to make a whole new set of figures! It displays how literacy rates and enrollment change from the 1950s to the 1990s, with countries in red if they get girls in school but fail to get them literate by grade 5, green if they succeed.