One day I showed my father a copy of some tattoos from the ‘Crosses’ (solitary confinement cells), where I worked as a supervisor, and he said to me, ‘My son, collect the tattoos, the convicts’ customs, their anti-social drawings, or it will all go to the grave with them.’ He taught me the methodology for documenting prison folklore and how to encode material, which was essential to the dangerous undertaking. For thirty-three years I, a ward of a home for children of ‘enemies of the people’, an artist with an incomplete education who fought in the Second World War, worked in the Ministry of the Interior. For all those years I collected material on the language and folklore of the criminal world. Thanks to a free ticket, I travelled four times from Leningrad to Vladivostok and visited

Topics:

Chris Blattman considers the following as important: art, Books, prison, Russia, tattoo

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Robert Skidelsky writes House of Lords Speech – Ukraine: “A wake up call” (International Relations and Defence Committee Report)

Robert Skidelsky writes The American Conservative – Why Is the UK So Invested in the Russia–Ukraine War?

Robert Skidelsky writes The American Conservative: Skidelsky on Russia, Ukraine and the Future of European Security

One day I showed my father a copy of some tattoos from the ‘Crosses’ (solitary confinement cells), where I worked as a supervisor, and he said to me, ‘My son, collect the tattoos, the convicts’ customs, their anti-social drawings, or it will all go to the grave with them.’ He taught me the methodology for documenting prison folklore and how to encode material, which was essential to the dangerous undertaking.

For thirty-three years I, a ward of a home for children of ‘enemies of the people’, an artist with an incomplete education who fought in the Second World War, worked in the Ministry of the Interior. For all those years I collected material on the language and folklore of the criminal world. Thanks to a free ticket, I travelled four times from Leningrad to Vladivostok and visited dozens of corrective labor camps and colonies.

…I was reported to the KGB, but unexpectedly they supported me. They realized the value of being able to establish the facts about a convict or criminal: his date and place of birth, the crimes he had committed, the camps where he had served time, and even his psychological profile.

That is Danzig Baldaev in his book Russian Criminal Tattoo: Encyclopedia Volume I.

Many of the photos and tattoos are NSFW, to say the least. Here is a selection of the more interesting and SFW entries.

(Below) “A convict’s tattoo signifying ‘lam a recidivist convict. I have no resources to support a conscience’.”

(Below) “An anti-Soviet tattoo, from a prisoner arrested for petty hooliganism. Drawn in a corrective labour camp in the Pechow camp system in 1952, during a six year sentence for theft.” It reads: “The convicts of the GULAG are the new nation of the USSR bred by the Marxist devils!

(Below) The tattoo reads “Daisy”. From the book, “This is the tattoo of a ‘passive’ homosexual that has been forcibly applied in prison. In criminal jargon a passive homosexual is also called a ‘daisy’, ‘Mashka’ (a woman’s name), ‘cockerel‘, ‘coxcomb’, ‘queer’, ‘cocksucker’, ‘gay’ or ‘piglet’.”

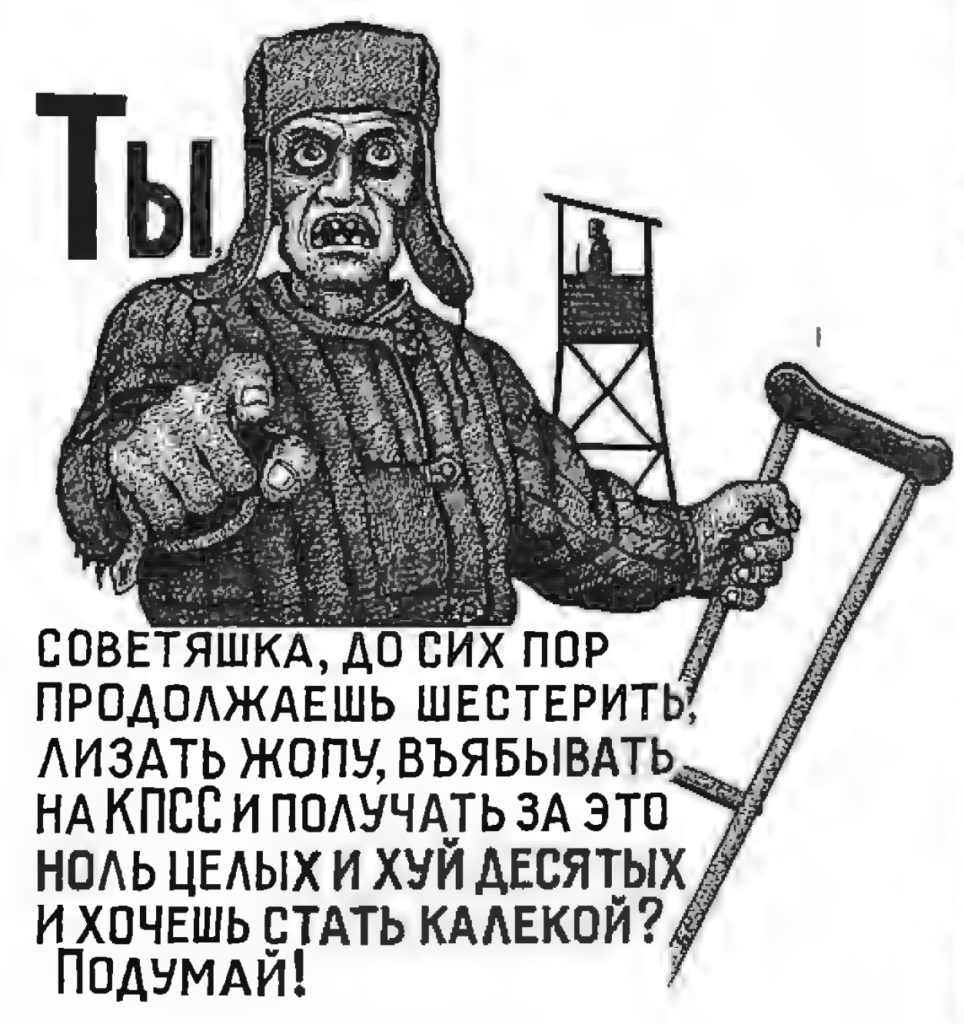

(Below) “A tattoo widespread in the camp zone in the 1950s and I 960s. An imitation of a well-known Civil War poster.” It reads: “You little Soviet shit, you are still kow-towing, arse-licking and flogging away for the CPSU and being paid zero point fuck-all and do you want to be a cripple? Think about it!”

(Below) “A ‘grin’ directed against the authorities, drawn on the left buttock, (the right buttock had an image of the order of Lenin), of a prisoner convicted for speculating in foreign goods acquired from merchant seamen.” It reads: “The chief great Russian swine!”

(Below) “A ‘grin’ directed against the authorities, drawn on the left buttock, (the right buttock had an image of the order of Lenin), of a prisoner convicted for speculating in foreign goods acquired from merchant seamen.” It reads: “The chief great Russian swine!”

I have bought but never had time to read Federico Varese’s Russian Mafia and Mafia Life. I am now inspired to do so.