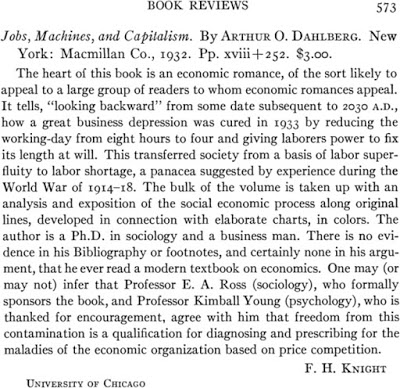

In his preface to Jobs, Machines and Capitalism, Arthur Dahlberg explained that the economic views upon which his book was based were inspired by his reading of Stephen Leacock's The Unsolved Riddle of Social Justice. The latter book's inspiration can be summarized in the sentence, "The economics of war, therefore, has thrown its lurid light upon the economics of peace." Contrary to Frank Knight's dismissive arm-waving about bibliographies and footnotes, Dahlberg did in fact cite two economics textbooks along with contemporary economists such as Leacock, Wesley Mitchell, Thorstein Veblen and John R. Commons. One may infer from the sarcastic comment at the end of his review that Knight failed to grasp Dahlberg's (and Leacock's, Mitchell's, Commons's and Veblen's) point that the

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

Among the opposers of this doctrine there were (and still are) prominent so-called 'economic experts' closely connected with banking and industry. This suggests that there is a political background in the opposition to the full employment doctrine, even though the arguments advanced are economic.

...if a dynamic expansion of the economy were achieved, the necessary build-up could be accomplished without a decrease in the national standard of living because the required resources could be obtained by siphoning off a part of the annual increment in the gross national product.Twelve years later, Clyde Dankert counseled against "any sizable reduction" in hours "in view of the current cold war situation":

If shorter hours are to be advocated today -- and in view of the current cold war situation the present writer would not recommend any sizable reduction in them just now -- it would seem desirable to use, not the arguments of the past, but a more comprehensive and up-to-date argument. The one here suggested points to the maximization of worker satisfactions as the objective.I was led to these ruminations by the reading I assigned for last week to my Politics of Working Time class, Benjamin Hunnicutt's "The End of Shorter Hours." Hunnicutt cited standard economists' arguments for why the movement for shorter hours in the United States faded away after World War II and proposed his own explanation. Hunnicutt cited "the reduction of fatigue, availability of consumer credit, commuting time, stability of employment, easier work, pent-up consumer demand, increased cost of education and raising larger families, and stable cost of recreation" as the typical explanations for the demise of the movement given by economists.

Hunnicutt's own explanation consisted of a combination of subjective distaste for "idleness" arising out of the depression experiences of unemployment, the influence of the business philosophy of "the new economic gospel of consumption," a new commitment from government to maintain full employment through government spending and public works, and the consequent erosion of the idea that "work-sharing" was necessary to combat technological unemployment. In his subsequent book, Work Without End: Abandoning Shorter Hours for the Right to Work, Hunnicutt did address the factor of military spending in a paragraph toward the end of the last chapter.

The economics of war has thrown its lurid light upon the economics of peace.