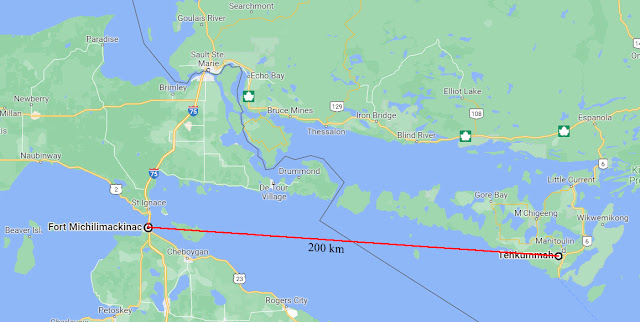

As the crow flies, it is around 200 kilometers from Michilimakinac, where Kandiaronk's Wyandot people settled in 1671, when he was around twenty years old, to Tehkummah on Manitoulin Island where Isabel Paterson was born 215 years later. It gets even cozier because the Wyandot had been displaced from the south shore of Georgian Bay by the Iroquois Five Nations, who around the same time also displaced the Oddawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi people from Manitoulin Island. The latter three tribes formed the Council of Three Fires, which also relocated to Michilimakinac and formed alliances with the Wyandot and other tribes.One of the threads that I am weaving derives from David Graeber's and David Wengrow's account of how Kandiaronk's (or Kondiaronk's) criticisms of European customs became the

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

One of the threads that I am weaving derives from David Graeber's and David Wengrow's account of how Kandiaronk's (or Kondiaronk's) criticisms of European customs became the basis for the Enlightenment critique, which was subsequently blunted by Turgot's theory of four evolutionary stages of society and Rousseau's ambivalent recuperation of the Noble Savage. Graeber and Wengrow got their argument from Ronald Meek's 1971 account.

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Baron de l'Aulne, commonly known as Turgot maintained in his 1750 lecture that there were four economic stages of society: hunter-gatherers, pastoral, agriculture and finally commercial society. Nearly 200 year later, Isabel Paterson described the "only four general ways by which human beings can exist" as the following:

(1) The savage society, or "snatch economy," of wandering hunters who live by the bounty of nature, on what they can kill or pick up.

(2) The pastoral nomad society, wandering herdsmen who live in the main off their tame animals.

(3) The agricultural society, in which men have learned to get most of their living from cultivated crops.

(4) The industrial economy, ranging all the way from handicrafts to high-speed, high-energy motor machine production; and requiring a general exchange system.

By 1948, the four-stages myth had become canon. It was also amplified by social Darwinism as practiced by Herbert Spencer and his American disciple, William Graham Sumner. Sumner's doctoral student, Thorstein Veblen, adopted Sumner's perspective of social evolution but jettisoned the laissez-faire component of his teachings.

Paterson may or may not have read Sumner but she was friends with Stuart Chase, a follower of Veblen and a casual associate of the Technocracy movement inspired by Veblen. It would have been easy for her to reverse engineer Sumner's position by fusing laissez-faire economic doctrine to Chase's and Veblen's social evolutionary perspective. Technocracy without the altruism.

As so often happens, my something-completely-different dive down the Ayn Rand/Isobel Paterson rabbit hole has started to converge chronologically and thematically with my previous progressive/planned obsolescence thread featuring Herbert Marcuse, Thorstein Veblen, Georg Simmel, Christine and J. George Frederick, et al.

Marcuse adopted his persistent (albeit analytically shallow) obsession with planned obsolescence from Vance Packard, whose inspiration was... Stuart Chase's The Tragedy of Waste. While Paterson's and Ayn Rand's individualist vision was grounded in nostalgia for a mythical 19th century American heroic inventor/businessman type, Marcuse's hopes for liberation dwelt on a resigned anti-nostalgia for the mythical 19th century class-conscious revolutionary proletariat.

While Paterson and Rand were idolizing mythical productivist heroes, actual businessmen and women like the Fredericks, Paul Mazur, and Edward Bernays were laying the foundation of a consumer society. They saw the barrier to economic dynamism as insufficient demand, not excessive government.

I was unable to find any commentary on Rand by Marcuse. Rand, however, had a few choice words for Marcuse:

When every girder of capitalism had been undercut, when it had been transformed into a crumbling mixed economy—i.e., a state of civil war among pressure groups fighting politely for the legalized privilege of using physical force—the road was cleared for a philosopher who scrapped the politeness and the legality, making explicit what had been implicit: Herbert Marcuse, the avowed enemy of reason and freedom, the advocate of dictatorship, of mystic "insight," of retrogression to savagery, of universal enslavement, of rule by brute force.

Note the "retrogression to savagery" trope -- the ghost of Turgot. In a sense, Marcuse and Rand were looking glass images of each other, each trapped in their adjacent funhouse mazes of obsolescence and nostalgia, a trope handed down from Turgot to Spencer to Sumner to Veblen... and Chase... and Packard.

The function of the four-stages myth was to deny the critique of social hierarchy. The illusion of a "progressive" stage theory leads back into the maze it is trying to escape from.

Is there a way out of that maze? I think there is -- at least intellectually. The way out -- and forward -- involves revisiting the "second storey" under historical materialism that Georg Simmel constructed and re-examining Marx's scaffolding for the Grundrisse that he dismantled in the published volume one of Capital. It seems to me that there is a way to contend with the gap between objective culture and subjective culture, collectively.