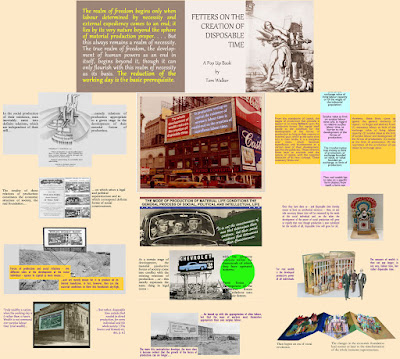

Around three years ago I made a pop-up book titled Three Fragments on Machines, that contained a collection of quotes from the Grundrisse that illustrated some of the research I had been doing related to disposable time in Marx's theory. Last spring, I started work on another pop-up book showing the connection between the Grundrisse and Marx's more famous reference to forces of production, relations of production, and fetters from his Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. I abandoned that project when the designs started to get too complicated.Now I am coming back to that second project but with a less ambitions design and more sparing textual approach -- what I consider now as a "second edition" of Three Fragments. Central to this new edition is a mash-up of

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

Around three years ago I made a pop-up book titled Three Fragments on Machines, that contained a collection of quotes from the Grundrisse that illustrated some of the research I had been doing related to disposable time in Marx's theory. Last spring, I started work on another pop-up book showing the connection between the Grundrisse and Marx's more famous reference to forces of production, relations of production, and fetters from his Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. I abandoned that project when the designs started to get too complicated.

Now I am coming back to that second project but with a less ambitions design and more sparing textual approach -- what I consider now as a "second edition" of Three Fragments. Central to this new edition is a mash-up of texts from the 1859 Preface and from notebook VII of the Grundrisse. Marx wrote the Preface in January, 1859; notebook VII was written between February and June of 1858. The Preface clearly reiterates arguments contained in the Grundrisse but leaves out important details that can be fleshed out by attention to similar phrasing in the latter work.

I have finished the "flat" draft of my pop-up book, "Fetters on the Creation of Disposable Time." Now I move on to the mock up stage in which these images attain their third dimension -- 3-D! I have been wondering about how to get this project out to a wider public and this morning thought about the "thousand cranes" legend and Sadako Sasaki's enactment of the legend for peace. Both origami and pop-up books are made by folding paper. Masohiro Chatani wrote a series of pop-up how-to books that he called "origamic architecture." I will make 1000 copies of this book (which is a tall order).

As the project unfolds, I hope to recruit collaborators to cut, fold and paste the books and even automate parts of the process with die cutting and its own high-quality printer. I would like to give talks about what the book is trying to say and how it came about.

I have been working with the texts used in the book for over two decades and with photo-montage pop-ups for over four decades. The method of this work comes from Walter Benjamin's "N [Theoretics of Knowledge;Theory of Progress]" from his unfinished Arcades Project, the first thesis of which is "In the fields with which we are concerned, knowledge comes only in flashes. The text is the thunder rolling long afterward."

What Benjamin called the "pedogigic side of this project" was, quoting Rudolf Borchardt, "'To train our image-making faculty to look stereoscopically into the depths of the shadows of history.'"

One more thesis from N: "The work must raise to the very highest level the art of quoting without quotation marks. Its theory is intimately linked to that of montage."

In my pop-up book, I am stereoscopically reading two texts by Marx -- written a few months apart in 1859 -- that I have combined into one. The "first" is from Marx's Preface to his Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (it is actually the later historically). This short summary by Marx of the principles that guided his research through the 1850s became the canonical statement of "historical materialism" in its "classical", "traditional", or "orthodox" formulation of the 2nd and 3rd Internationals.

The second text -- written around six months earlier -- is from Marx's manuscript notebook VII, published posthumously as the Grundrisse. Putting the two texts side by side reveals that they present, in fact, one continuous image with a depth of field that has been excluded from the canonical interpretation of historical materialism. Missing from that classical view is Marx's emphasis on disposable time, which was central to the Grundrisse text. I have added "footnotes" from notebook IV of the Grundrisse that emphasize the importance of disposable time and that explain what the "fetters on the development of the productive forces" are, specific to capital.

Marx's vision of "the realm of freedom," outlined in his 1864-65 draft for volume III of Capital, returned decisively to disposable time (without mentioning the word) in prescribing "The reduction of the working day [as] the basic prerequisite" for achieving the realm of freedom.

The text in black below is from the 1859 Preface. The text in red is from the Grundrisse.

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness.

Forces of production and social relations - two different sides of the development of the social individual - appear to capital as mere means, and are merely means for it to produce on its limited foundation. In fact, however, they are the material conditions to blow this foundation sky-high. ‘Truly wealthy a nation, when the working day is 6 rather than 12 hours. Wealth is not command over surplus labour time’ (real wealth), ‘but rather, disposable time outside that needed in direct production, for every individual and the whole society.’ (The Source and Remedy etc. 1821, p. 6.)

The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or – this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms – with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters.

The more this contradiction develops, the more does it become evident that the growth of the forces of production can no longer be bound up with the appropriation of alien labour, but that the mass of workers must themselves appropriate their own surplus labour. Once they have done so - and disposable time thereby ceases to have an antithetical existence - then, on one side, necessary labour time will be measured by the needs of the social individual, and, on the other, the development of the power of social production will grow so rapidly that, even though production is now calculated for the wealth of all, disposable time will grow for all. For real wealth is the developed productive power of all individuals. The measure of wealth is then not any longer, in any way, labour time, but rather disposable time

Then begins an era of social revolution. . The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.

From the perspective of capital, the stages of production that precede it can be seen as imposing so many fetters upon the productive forces. But correctly understood, capital itself operates as the condition for the development of the forces of production only so long as they require an external spur, which, however, at the same time acts as their bridle. It is a discipline over them that becomes superfluous and burdensome at a certain level of their development, just like the guilds etc. These inherent limits coincide with the nature of capital, with the essential character of its very concept. These necessary limits are:

- Necessary labour as limit on the exchange value of living labour capacity or of the wages of the industrial population;

- Surplus value as limit on surplus labour time; and, in regard to relative surplus labour time, as barrier to the development of the forces of production;

- What is the same, the transformation into money, exchange value as such, as limit of production; or exchange founded on value, or value founded on exchange, as limit of production. This is:

- again the same as restriction of the production of use values by exchange value; or that real wealth has to take on a specific form distinct from itself, a form not absolutely identical with it, in order to become an object of production at all.

However, these limits come up against the general tendency of capital to forget and abstract from: (1) necessary labour as limit of the exchange value of living labour capacity; (2) surplus value as the limit of surplus labour and development of the forces of production; (3) money as the limit of production; (4) the restriction of the production of use values by exchange value.

Footnote 2, "disposable time"

The whole development of wealth rests on the creation of disposable time. ... In production resting on capital, the existence of necessary labour time is conditional on the creation of superfluous labour time.