This chapter is part of our guide to making the case for community-led housing on public land. Making the case1. The context: legislation and regulations2. Addressing the ‘best consideration’ requirement – and winning3. Case studies4. Building an evidence base5. Backing up your arguments This section outlines steps groups need to take to make the case that community-led affordable housing schemes generate economic and social value, in order to convince public authorities to enable schemes on public land. It provides an outline of a possible approach, and signposts to existing resources. The information in this section is based on a review of in-depth work done by the Housing Association Charitable Trust (HACT) since

Topics:

neweconomics considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

This chapter is part of our guide to making the case for community-led housing on public land.

Making the case

1. The context: legislation and regulations

2. Addressing the ‘best consideration’ requirement – and winning

3. Case studies

4. Building an evidence base

5. Backing up your arguments

This section outlines steps groups need to take to make the case that community-led affordable housing schemes generate economic and social value, in order to convince public authorities to enable schemes on public land. It provides an outline of a possible approach, and signposts to existing resources.

The information in this section is based on a review of in-depth work done by the Housing Association Charitable Trust (HACT) since 2012 on how to financially value the social benefits of affordable housing. HACT’s work is rigorous, comprehensive and provides clear ’how-to’ guides which we will not replicate here. Instead we provide links where you can find this work. However, HACT’s method focuses on building an evidence base for existing projects. Here we outline how to adapt HACT’s methods to develop the projected benefits of a proposed project. This uses Social Return on Investment (SROI), an approach often used by our partners NEF Consulting to establish the social returns of projects.

This should not be read as a guide to producing either a full social value analysis, or SROI, which is a more complex and resource intensive process than that outlined here. Instead, it is a guide for a quicker approach that can get a general case for community-led housing projects.

1: Develop a ‘theory of change’

A theory of change (ToC – also called an ’impact map’) details the kinds of infrastructure, amenities, services and activities that your project will develop, and links this to immediate and longer term outcomes. A good start for developing a theory of change is to get together as a group and write processes, practices, outputs and outcomes on PostIt notes, then form a visual map of these that includes the links between them. (More information on how to lead this process can be found here.) The final diagram should be supported by written paragraphs taking the reader through the logic of the ToC, i.e. the connection between activities and outcomes. Writing this out can be very useful in checking that your diagram does in fact make sense. When developing your ToC it is preferable to back the links you make between these with evidence (for some of this you can refer to the final section of this guide).

NEF Consulting offers training on how to carry out Theory of Change. For more information, click here.

Pitching it right

In our experience, different public bodies respond very differently to different types of evidence. Some like the concept of social value, some only want direct resource savings. It is advisable to research what the body in question might prefer. Though it can be tempting to try and put a value on everything this will be exhausting and also unlikely to seem credible. It is best to focus on outcomes that will be of interest to the body that you are negotiating with. As different public sector bodies have different incentives and interests (e.g. local authorities will have different incentives and interests from the NHS) it is worth doing some research into the kinds of evidence that body has accepted in the past.

Some, particularly local authorities, are interested in intangible social value (such as the wellbeing value of volunteering), but the most convincing forms of evidence across the board will be those that lead to direct resource savings – and intangible social value is generally seen as a ‘nice to have’ addition rather than the foundation for investment. However, cash savings are often hard to project. For example, one project we are working with is considering installing supported housing units on land it hopes to acquire from the NHS. This would be an example of an activity that could lead to direct savings, as it reduces demand on hospital beds by providing better supported housing. However, though this is beneficial in reducing demand, it is notable that it may not actually lead to savings because those hospital beds will likely be taken up by others.

2: Calculate cost/investment

A full SROI analysis would include all investments made in the project (social, physical and financial). However, for simplicity we recommend if you want to make the case for a public body to release land for housing development, that you limit the investment/cost side of the analysis to the projected costs for the public body in agreeing to use the land in question for your housing scheme. This way you can compare the benefits generated by the project with the costs for the public body, and make your case more clearly. It should be noted, however, that the project will generate further costs that need to be borne once land is secured.

Costs for the public body will depend on the details of the deal. However, the most common scenario will be that the public body in question sells the land at undervalue, or even gifts it – in which case the total cost or investment would be the full estimated market value of the land minus the price for which it was sold or leased to your organisation.

3: Calculate the financial value of your thoery of change outcomes

In order to calculate a financial value for these outcomes you need to consider several things for each outcome.

The number of people taking part and benefiting from infrastructure/activities: Remember to be realistic when estimating how many people will benefit. The total number of potential beneficiaries is your benchmark. However, you also need to consider ’uptake rate’ (subtracting those who do not take up opportunities) and ’retention rate’ (subtracting whose drop out). This will reduce the number of actual beneficiaries.

Using existing data on costs/benefits/income from these to generate a figure: HACT’s social value bank and value calculator provides the necessary data for any intangible benefits. For resource savings, the best source is New Economy Manchester’s cost benefit database.

The length of time over which benefits occur: You can start with one year of savings, but building infrastructure will last a long time. Project benefits forward for as many years as they will accrue – but you need to ‘discount’ the benefits each year. ‘Discounting’ means taking off some value of investment per year to account for the fact that things are more valuable in economists’ minds if they happen sooner. Government guidance suggests discounting by 3.5% per year.

Note that when making projections it is best to report higher and lower bounds – this means reporting numbers ranging from your most positive to most negative assumptions. You should also report on lower and higher bound yearly ranges both by unit (e.g. reducing mental health for one person or getting one long term unemployed person into a job) and in aggregate (e.g. total unemployment reduction associated with project) where applicable.

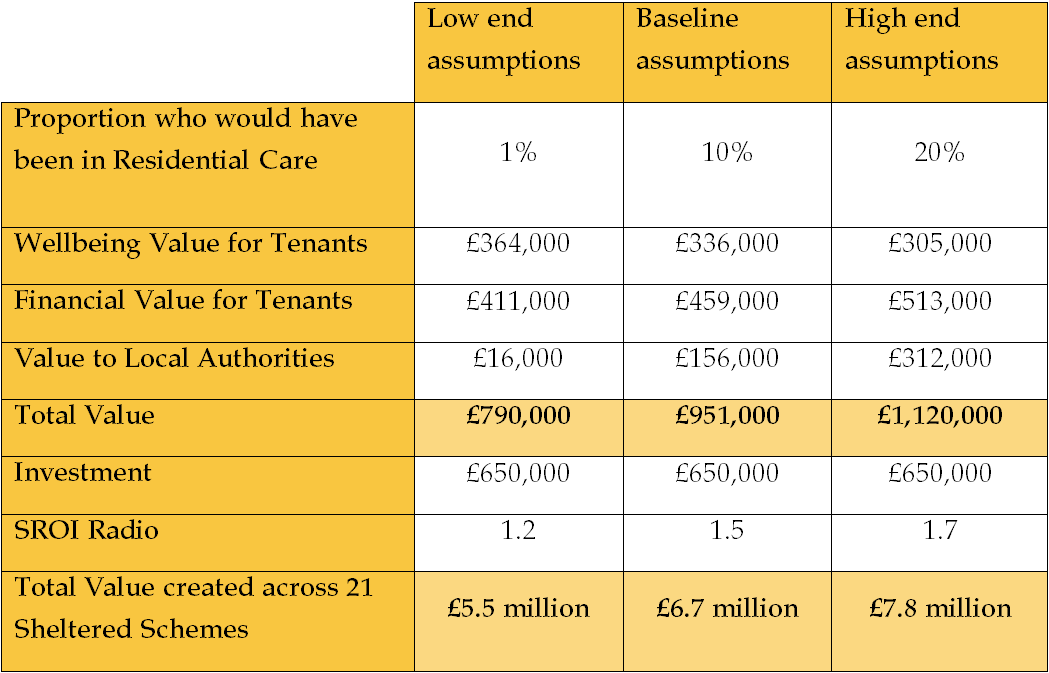

The table below shows an example. It is taken from an SROI done by NEF Consulting on a Sheltered Housing scheme. It reports low-end, baseline and high-end assumptions regarding the aggregate value generated for tenants (in terms of finance and wellbeing) and for local authorities. It compares this to the overall level of investment and develops a Social Return on Investment ratio.

Value created by Sheltered Housing scheme, NEF Consulting

The outcomes generating value in the three areas of the table above were:Value created by Sheltered Housing scheme, NEF Consulting

- Wellbeing value for tenants: increased security and safety; reduced isolation; increased sense of self-worth and confidence (mainly through collective activities that build social capital);

- Financial value for tenants: reduced expense of residential care provision;

- Value to Local Authorities: reduced expense of residential care provision; reduced expense in social services and social care.

More resources

Adopting these methods might sound daunting but there is support out there. Learning how other groups have navigated these questions is a good first step. For some examples, refer to the below organisations and cases who might be able to offer further practical guidance:

- Igloo’s footprint

- Power to Change’s Community-led Housing Programme

- Leeds Community Homes

- Co-housing Network

- The Rural-Urban Synthesis Society

There are also further resources for addressing ‘best consideration’:

- HACT’s social value bank: this details the yearly social values per person of a wide range of different activities/outcomes. Note that these are wellbeing values that may not lead to direct savings – the New Economy model is better for this.

- New Economy Manchester’s value bank: details the yearly values per person for a wide range of fiscal and economic savings, in the areas of crime, health, housing and more. Like HACT, they have also developed an Excel-based tool.

- HACT’s value calculator: a ready-to-use tool to calculate social values of different activities/services that can be used to produce a spreadsheet to calculate social impact based on your data. It includes: descriptions of each value and the evidence needed to apply it; an easy-to-read table of which values can be added together and which cannot; an automatic ’average deadweight’ figure to subtract ‘what would have happened anyway’ and therefore cannot be attributed to your project; five surveys to collect the evidence needed to apply selected values; a page summarising results and comparing cost to benefit. It also includes descriptions of the kind of data needed to measure specific values rigorously.

- Measuring Social Impact of Community Investment: a clear, step by step guide on how to put financial values on social activities that shows community investors how they can apply wellbeing analysis. This method can be adapted to make projections, by establishing a lower bound and a higher bound estimate. The social value practice notes complement this report – answering questions that arose as organisations applied the guide. The approach has been applied and further developed in a series of reports: a 2017 report valuing housing and local environment improvements produced evidence in favour of taking into account environmental improvements when developing housing in the; and a 2016 comprehensive value assessment developed a guide for identifying new activities and outcomes to measure that were not in the original guide.

This guide was created with the generous support of the Nationwide Foundation.