High rents. Evictions and insecure tenancies. Millions of families priced out of home ownership. Over a million households on the waiting list for social housing. The effects of our broken housing system are all too obvious. What is less obvious, but no less broken, is the market which sits beneath the housing market, and drives many of the worst aspects of it. When we talk about high rents, or high house

Topics:

neweconomics considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

High rents. Evictions and insecure tenancies. Millions of families priced out of home ownership. Over a million households on the waiting list for social housing. The effects of our broken housing system are all too obvious.

What is less obvious, but no less broken, is the market which sits beneath the housing market, and drives many of the worst aspects of it. When we talk about high rents, or high house prices, what we are really talking about is the unaffordability of land. Any solution to the housing crisis will never succeed unless it takes major steps to address the broken land system.

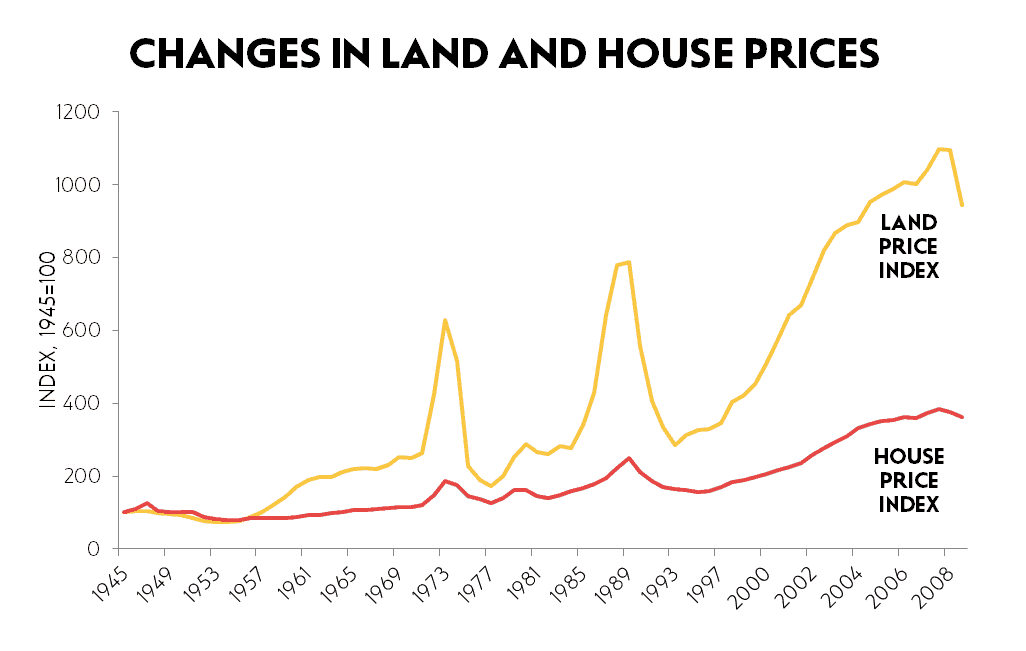

The value of a house is made up of two distinct components: the value of the building itself (the ‘bricks and mortar’), and the value of the land that the structure is built upon. Generally, land is the larger of the two – the biggest cost when buying, or building homes, is the land that they sit on. It’s not at all surprising then, that the price of homes is driven by the price of land, as the graph below indicates.

Reference: Rethinking the economics of land and housing, Ryan-Collins, Lloyd and Macfarlane

But what fixes the price of land? By far the largest proportion of the cost of land is ‘location, location, location’ – the cost of benefiting from being in that specific village, or part of a city. And what determines the cost of a specific location? Investment – public, community and private – in place. The hospital, tram network, nice park, or workplaces which make places desirable to live in.

These locational factors make the price of land unique. The benefits (and disadvantages) of a piece of land are almost entirely dependent on its unique location. In the UK system, this uniqueness gives landowners a huge degree of power and control over the price they can command for desirable sites, and particularly the sites in areas where there are high levels of demand for housing.

Landowners almost inevitably sell to the highest bidder. These highest bidders are private, speculative housing developers, who bid high on the assumption that they can sell the homes at sky-high house prices. And because land acquisition is usually the largest single cost in new house building, the price the developer pays determines much of what happens on site. In a competitive market for land, the developer that makes the most bullish expectations of sale prices will be able to offer the landowner the most and secure the site. These frenzied bidding wars favour developers who make the most cavalier assumptions about what they can afford to pay for land and still make a profit.

These frenzied bidding wars favour developers who make the most cavalier assumptions

Combined with landowners’ control over access to prime development sites, this results in a speculative fever over land. This drives developers to cut costs elsewhere – lower construction costs, little infrastructure, and particularly using the ‘viability’ loophole to evade building any social housing. High land values push up house prices and rents, and depress the production of social housing.

This frenzy of speculation means that, in the UK, landowners have too much power over what gets built in our communities. Instead of community need dictating what gets built on a site, land prices dictate what the wider community gets from development. Once a piece of land has been bought by a developer for a sky-high price in the overheated land market, it can often make the production of anything but the most expensive homes for rent and sale loss-making.

Behind the housing crisis sits a crisis in the affordability of land. The power of landowners to set the sale price, and their capture of enormous windfall financial benefits for doing little other than owning a piece of land, skews our broken development model before a single brick has been laid. Anyone serious about building a fairer housing system must start with the land that sits beneath it.

This article originally appeared on Shelter’s New Civic Housebuilding