It is impossible to shut out so large a proportion of the population from something as essential as housing and not ultimately pay the political price. So it’s not surprising that both the Government and the Opposition are flexing their policy biceps to find solutions. As Millennials push their way through the demographic strata, a tipping point grows ever nearer. Home ownership, which peaked in England at 71% of households in 2003, has fallen to 64%; fewer than two thirds of adults own their own home. Arguably, the factors that drove home ownership in this

Topics:

neweconomics considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

It is impossible to shut out so large a proportion of the population from something as essential as housing and not ultimately pay the political price. So it’s not surprising that both the Government and the Opposition are flexing their policy biceps to find solutions.

As Millennials push their way through the demographic strata, a tipping point grows ever nearer. Home ownership, which peaked in England at 71% of households in 2003, has fallen to 64%; fewer than two thirds of adults own their own home. Arguably, the factors that drove home ownership in this period cannot be repeated; this trend is almost certainly irreversible.

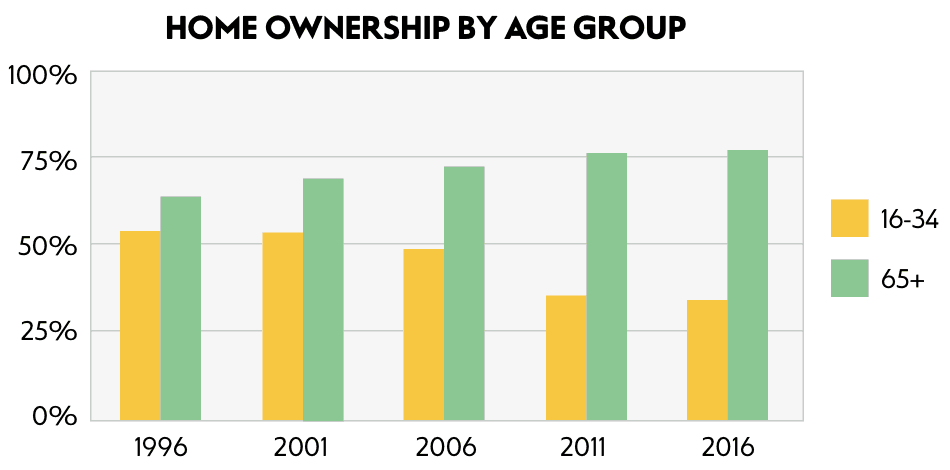

Home ownership rates are even more striking by age. 20 years ago, more than half of under-35 year olds were on the property ladder. By 2016, fewer than than one third of under-35s had bought, while Baby Boomers over 65 steadily increased their grip on the housing market. In essence, the Baby Boom Generation – and to some extent Generation X – are really the Private Housing Boom Generations.

Source: Home Ownership and Renting: Demographics, House of Commons Library

Back when Baby Boomers were under 35, people typically spent between five and 10% of their income on housing. Millennials are spending up to three times that; those paying the most are, unsurprisingly, renting privately. It’s fair to assume that with family equity locked up in their parents’ and grandparents’ houses – presumably for longer because of increased life expectancy – even the better off among this age group are prisoners of the economics of land and housing.

It’s also likely that housing equity will be depleted by the time Millennials get their hands on it because of the cost of end of life care and the high probability that most people’s savings won’t be enough to cover it. Typically, many Baby Boomers will have to to sell their property to meet this shortfall – another complex and intractable problem.

And so, as Westminster seems to be slowly realising, the politics that have for several decades favoured safeguarding house price increases, subsidising homeowners with low interest rates, and trying to push as many people as possible onto the bottom rung of the housing ladder, are inexorably shifting.

“Back when Baby Boomers were under 35, people typically spent between five and 10% of their income on housing. Millennials are spending up to three times that”

Even though older people tend to vote in greater numbers, ignoring the growing proportion of the population that is locked out of home ownership and – more importantly – into high cost and poor quality private renting is not only immoral, it is politically unsustainable. Even older homeowners are increasingly uneasy about their children turning 30 and being unable to leave the family home.

Tory policy grandee Sir Oliver Letwin has been appointed to lead a review of the practice of land banking, when developers acquire land and are granted planning permission to build homes, but sit on the land instead. Letwin’s task is to explain the gap between the amount of planning permissions granted and the number of houses built and recommend how to close it. But most in the housing policy world know what the problem is already: developers can benefit more from the increasing value of the land than from building and selling homes on it.

The assumption behind the Letwin review is that the solution to the housing crisis is to get private developers building: supply more housing and prices will fall. But that alone almost certainly won’t solve the problem because the link between supply and house prices is complicated, and barring a major collapse in prices, most of those locked out will still lack the means to buy a home.

If the Letwin Review concluded that so-called ‘hope value’ – the difference between the value of a piece of land depending on its current use and its value once planning permission for house building has been granted – is the problem that needs solving, then the review could be worthwhile. But that is not explicitly in his terms of reference.

In the meantime, Labour’s Shadow Housing Minister John Healey has floated a more radical idea, similar to one that NEF and others proposed in the run up to last year’s Budget, as part of our campaign to stop the sale of public land and use it for public good.

“With the speculative value of the land stripped away, it could then be used to build genuinely affordable housing.”

His proposal is to establish a People’s Land Trust, through which the Government would look to force land-banking developers to sell their land the State at a price that did not include its it’s ‘hope value’. With the speculative value of the land stripped away, it could then be used to build genuinely affordable housing.

For NEF, the ‘People’s’ bit is important, though. Politicians picking up this proposal need to recognise that swapping the failings of the current market for a 60s-style, homogenous push from the State will ultimately beget further problems. Government’s job is to intervene in the land and housing crisis to solve the big problem of land value, so that councils, housing associations and tenants can work together to get the bricks and mortar in place.

The Boomer-loving Daily Mail of course hates the the idea, branding it a ‘land grab’. But experts like Shelter and MPs weighing up the politics are less dismissive. It’s also worth remembering that the Conservative Party Manifesto contained a pledge to “reform Compulsory Purchase Orders to make them easier and less expensive for councils to use and to make it easier to determine the true market value of sites.” This isn’t so dissimilar to Labour’s proposal.

And as the demographics push inexorably towards the need for a solution to the housing crisis, it almost certainly won’t be the Daily Mail calling the shots. It’s time for something very big to happen in housing. If politicians don’t grasp that, then the problem is likely to grasp them.