Blog Beyond the £20 uplift Options for reforming universal credit By Sarah Arnold, Dominic Caddick, Alfie Stirling 27 September 2021 The UK is facing a cost of living crisis which is set to sharpen significantly for those on the lowest incomes over the next few months. Millions are going to be hit by a triple whammy of price increases for food and energy bills, welfare cuts and tax rises. In total, low-income families will see a squeeze of more than £1,700 per year by April. By far the most important

Topics:

New Economics Foundation considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

Beyond the £20 uplift

Options for reforming universal credit

27 September 2021

The UK is facing a cost of living crisis which is set to sharpen significantly for those on the lowest incomes over the next few months. Millions are going to be hit by a triple whammy of price increases for food and energy bills, welfare cuts and tax rises. In total, low-income families will see a squeeze of more than £1,700 per year by April.

By far the most important driver of this squeeze is the £1,040 per year cut to universal credit (UC) due at the end of September. The UK safety net is already one of the weakest among advanced economies and in the UK’s own post-war history. Yet this is about to be compounded by the largest overnight cut to welfare in 70 years, hitting families disproportionately in the North East, West Midlands, and Yorkshire and the Humber.

The best way to understand the impact of the UC cut is to view it from the point of view of what different UK families actually need to get by, which is helpfully captured by the JRF’s ‘minimum income standard’ (MIS). Recent NEF modelling showed that when the uplift is removed, 21.4 million people, including 7 million children, will live in households that do not have the amount they need to afford the basics.

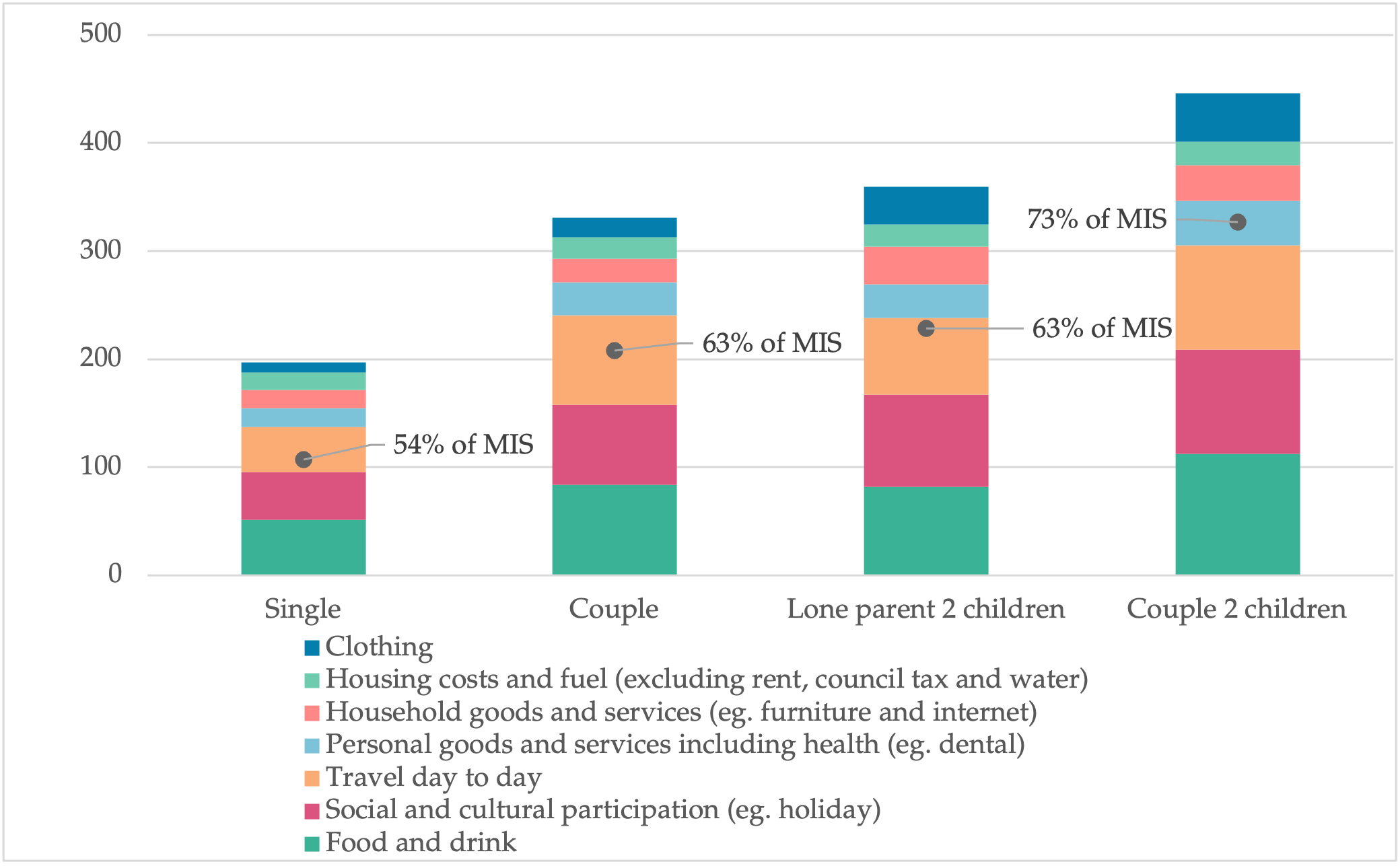

Not only this, but those that fall below the MIS fall significantly below. Even before the effects of energy price increases, the UC cut will leave the average single adult that is below the MIS with only 54% of the income they need to stay afloat, while the average couple with two children will have just 63% of the income they need.

This means choosing between essentials like food, clothes or a warm home, every single week.

Figure 1: Those falling below the MIS fall very far below

2021 MIS (excluding rent, council tax, and water) compared to the average net disposable income after housing costs for those below the MIS, for those on universal credit or the legacy benefits it is due to replace, for November 2021 when the £20 UC uplift is removed

Source: NEF analysis of JRF/CRSP MIS and Family Resources Survey using the IPPR tax benefit model

Using the MIS as a framework, however, allows us to examine the road to a far stronger safety net in the UK in a systematic way. New modelling by NEF has taken a series of example packages of reforms to UC to understand their effects for different families. All modelling has been forecast for 2026/27, when UC is expected to be fully rolled out, to best gauge the long-run effect of different reforms. And each package has been costed at approximately the same level as the £20 uplift in that year (£7.5 billion in 2026/27), to compare broadly similar levels of investment in the system.

Alongside a scenario where the £20 uplift remains in place, we also modelled the following non-exhaustive list of example reforms:

- Providing a £27 uplift to the amount of support a household receives for each child

- Removing the caps on support which limit the amount households can receive (the benefit cap and two-child limit), and providing a £12 per week uplift to the main adult element of support

- Lowering the taper rate at which benefits are withdrawn for every £1 of earnings, from 63% to 50%

- Expanding work allowances (the threshold beyond which the taper rate takes effect) to all claimants, and increasing the value of the work allowance for those who already achieve it by an hour at minimum wage

Table 1 below gives a quick summary of the different packages in terms of their effects on headline poverty rates (defined as families below 60% of median household disposable income). The results show that despite all the packages having similar price tags, investing in either the child elements of UC, or else combining a smaller increase in the adult element with the removal of the two-child limit and the benefit cap, has the biggest impact in terms of the overall number of people coming out of poverty.

Table 1: A comparison of alternatives of reform to different elements of UC compared to the £20 uplift

Cost and impact on household, adult, child and total people poverty (relative poverty at 60% of median income after housing costs) for a range of reforms to UC compared to UC without the £20 uplift, for a range of working and non-working households with and without children, 2026/27

£20 uplift |

£27 uplift to child elements |

£12 uplift, no benefit cap, no 2 child limit |

Reduce taper rate to 50% |

Expand and increase work allowances |

|

Cost relative to baseline (£ thousands) |

7,600 |

7,400 |

7,400 |

7,200 |

6,700 |

Change in relative poverty after housing costs |

|||||

Households |

-240,000 |

-240,000 |

-230,000 |

-160,000 |

-210,000 |

Adult |

-390,000 |

-370,000 |

-380,000 |

-300,000 |

-380,000 |

Children |

-220,000 |

-600,000 |

-530,000 |

-300,000 |

-210,000 |

Total people |

-610,000 |

-970,000 |

-910,000 |

-600,000 |

-590,000 |

Source: NEF analysis of JRF/CRSP MIS and Family Resources Survey using the IPPR tax benefit model

But you need to look beneath headline poverty rates to get a clearer view of what is going on for specific families. Table 2 below shows the effect of different example reforms by family type, with respect to each family’s MIS. Even by 2026/27, the extent to which families below the MIS are still falling short remains significant. But there is also clearly variation across families, and in the types of families that different reform options help most. The £20 uplift is particularly effective for non-working families without children. Topping up child elements is unsurprisingly more effective for increasing the incomes of families with children (whether in or out of work) and reducing taper rates or strengthening work allowances is the most cost-effective way to boost incomes for working families without children.

Table 2: Each different reform outperforms the £20 uplift for at least one family type

Median disposable household income after housing costs for a range of working and non-working households with and without children as a proportion of the Minimum Income Standard, adjusted to remove housing costs, for those on Universal Credit and already under the MIS, for a range of working and non-working households with and without children, 2026/27

No uplift (baseline) |

£20 uplift |

£27 uplift to child elements |

£12 uplift, no benefit cap, no 2 child limit |

Reduce taper rate to 50% |

Expand and increase work allowances |

|

Median disposable income as a proportion (%) of the MIS |

||||||

Couple with children, not working |

64% |

67% |

72% |

75% |

64% |

64% |

Couple without children, not working |

53% |

58% |

53% |

56% |

53% |

53% |

Lone parent with children, not working |

60% |

65% |

72% |

71% |

60% |

60% |

Single without children, not working |

54% |

63% |

54% |

59% |

54% |

54% |

Couple with children, working |

78% |

82% |

87% |

86% |

83% |

81% |

Couple without children, working |

72% |

77% |

72% |

75% |

79% |

76% |

Single with children, working |

76% |

80% |

86% |

82% |

79% |

77% |

Single without children, working |

64% |

73% |

64% |

70% |

75% |

81% |

Source: NEF analysis of JRF/CRSP MIS and Family Resources Survey using the IPPR tax benefit model

Note: For each household type, the most effective reform to get them closest to meeting their needs is highlighted

Table 3 presents a similar analysis by household type, only this time we look at the average change in weekly disposable income. The pattern in terms of where different packages are most effective remains the same, with the £20 uplift having the most even impact across families, and the impact for other packages more skewed towards either families with children or childless households in work. For example, boosting child elements increases disposable incomes for families with children on average by around £2,500 per year, and cutting the taper rate boosts incomes for working families by around £700 to £1,700 per year.

Table 3: Each reform affects household incomes differently

Average (mean) change in annual disposable household income after housing costs for a range of reforms to UC compared to UC without the £20 uplift„ for those on Universal Credit and already under the MIS and for a range of working and non-working households with and without children, 2026/27

£20 uplift |

£27 uplift to child elements |

£12 uplift, no benefit cap, no 2 child limit |

Reduce taper rate to 50% |

Expand and increase work allowances |

|||||||||||

£ annual |

% |

£ annual |

% |

£ annual |

% |

£ annual |

% |

£ annual |

% |

||||||

Couple with children, not working |

1000 |

5% |

2800 |

14% |

3100 |

16% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

|||||

Couple without children, not working |

1000 |

9% |

0 |

0% |

600 |

5% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

|||||

Lone parent with children, not working |

1000 |

7% |

2500 |

17% |

2500 |

17% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

|||||

Single without children, not working |

1000 |

18% |

0 |

0% |

600 |

11% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

|||||

Couple with children, working |

1000 |

5% |

2700 |

12% |

2500 |

11% |

1700 |

8% |

1100 |

5% |

|||||

Couple without children, working |

1000 |

8% |

0 |

0% |

600 |

5% |

1500 |

11% |

1400 |

10% |

|||||

Single with children, working |

1000 |

6% |

2500 |

14% |

1700 |

10% |

700 |

4% |

200 |

1% |

|||||

Single without children, working |

1000 |

15% |

0 |

0% |

600 |

9% |

1100 |

16% |

1500 |

22% |

|||||

Source: NEF analysis of JRF/CRSP MIS and Family Resources Survey using the IPPR tax benefit model

The key takeaway from all these findings is that the £20 uplift represents a vital reform that reaches across different family types. Removing it at any time, let alone during an economic crisis and pandemic, is a huge mistake. But the analysis also shows that the £20 uplift is not enough on its own, and that some families would benefit even more from alternative types of reform.

Policymakers and poverty campaigners should not only focus on keeping the £20 uplift in place but should also look ahead towards the next steps for improving the system. As NEF’s campaign for a living income is calling for, it is vital that the UK brings itself into line with other countries, by building a safety net that pays enough to live on.

To this end, we have also modelled the effects of further reforms to UC on top of the £20 uplift, to inform possible next steps towards a living income.

We consider two packages, one targeted at households with children (‘child package’), and one targeted at working households (‘work package’). In addition to retaining the £20 uplift, the former package involves removing the benefit cap and the two-child limit, as well as a £5 top up to the child elements of UC. The cost of this package comes in at around £6.2 billion per year by 2026/27, on top of the cost of retaining the £20 uplift. The second package is targeted at working families. In addition to the £20 uplift, it includes reducing the taper rate to 60% and extending work allowances to second earners — coming in at an additional cost of around £3.9 billion per year.

As Tables 4, and 5 below show, both these packages could be implemented together on top of the £20 uplift at around the same cost again as the uplift itself. The package gives an example of how future reform could reach a balance of different household types, lifting 1.7 million people out of poverty in total, including over 900,000 children and moving the median income for most family types to above 75% of the MIS and closer towards a living income.

Tables 4 & 5: Further UC reform could raise 1.7 million people out of poverty

Cost and impact on household, adult, child and total people poverty (relative poverty at 60% of median income after housing costs) for a range of reforms to UC, for a range of working and non-working households with and without children, 2026/27

Base |

Worker package |

Child package |

Combination |

|

Cost relative to baseline (£ thousands) |

7,600 |

11,500 |

13,800 |

16,300 |

Change in relative poverty after housing costs, compared with baseline |

||||

Households |

-230,000 |

-290,000 |

-420,000 |

-440,000 |

Adult |

-380,000 |

-530,000 |

-710,000 |

-780,000 |

Children |

-210,000 |

-380,000 |

-850,000 |

-940,000 |

Total people |

-590,000 |

-910,000 |

-1,560,000 |

-1,720,000 |

Average (mean) change in annual disposable household income after housing costs for a range of working and non-working households with and without children and as a proportion of baseline disposable income, for those on Universal Credit and already under the MIS, for a range of working and non-working households with and without children, 2026/27

WORKERS PACKAGE: £20 uplift to adult elements, 60% taper, 2nd earner in household with children has work allowance |

CHILD PACKAGE: £20 uplift to adult elements, £5 child, cap removed, 2 child limit removed |

COMBINED PACKAGE: £20 uplift to adult elements, 60% taper, 2nd earner in household with children has work allowance, £5 child, cap removed, 2 child limit removed |

|||||||

£ annual |

% |

£ annual |

% |

£ annual |

% |

||||

Couple with children, not working |

1000 |

5% |

4200 |

21% |

4200 |

21% |

|||

Couple without children, not working |

1000 |

9% |

1000 |

9% |

1000 |

9% |

|||

Lone parent with children, not working |

1000 |

7% |

3600 |

24% |

3600 |

24% |

|||

Single without children, not working |

1000 |

18% |

1000 |

18% |

1000 |

18% |

|||

Couple with children, working |

2200 |

10% |

4000 |

17% |

4700 |

21% |

|||

Couple without children, working |

1400 |

10% |

1400 |

10% |

1400 |

10% |

|||

Single with children, working |

1200 |

7% |

2800 |

16% |

2800 |

16% |

|||

Single without children, working |

1300 |

19% |

1300 |

19% |

1300 |

19% |

|||

To fund such reforms in the short term, it makes most sense to borrow at the UK’s ultra-low interest rates to strengthen the safety net as part of a recovery package from Covid-19. Most other countries are already doing this, recognising that failing to support incomes now will cost more in future jobs and tax receipts.

In the long run, it may require tax rises to help offset the extra public spending on low-income families. The best options would be to increase the taxation of income from wealth, for example by equalising capital gains tax with income tax, reducing tax relief on pension contributions for higher earners and reforming National Insurance into a flat contribution — which would see higher earners pay more than the present system, and lower earners contribute less. Table 6 shows the estimated revenues from such reforms, different combinations of which could be used to more than cover the costs of our illustrative UC proposals above.

Table 6: There are a range of potential progressive options to offset the extra public spending

Tax revenue source |

Revenue raised by 2026/27 (nominal prices) |

Source for calculation |

Equalising capital gains tax with income tax |

13.5bn |

|

Making pension relief flat at 20% |

8.3bn |

|

Equalising National Insurance Contributions for employees at 12% for all income levels that pay it (it is due to be 13.25% for incomes below £187 and 3.25% for every pound earnt above £770 by 2026/27, taking into account the health and social care levy) |

9.1bn |

NEF analysis of NICs equalisation calculated for 2026/27 using the IPPR Tax-Benefit Model |

We have shown that there are affordable options to reform UC so that it moves towards providing a Living Income for all different household types. It is vital that such reform occurs, in order for our society and economy to flourish post-Brexit. Maintaining the £20 uplift is a starting point, but there is still much further to go.