There have been a number of important developments in the Ontario electricity sector since my last update when I summarized my arguments in front of the Ontario Legislature against the proposed Provincial Conservative legislation, now enacted, that eliminated the Provincial Liberal rate-based borrowing scheme to subsidize electricity prices and replace it with Government revenues. The tax-payer financed subsidy of .8 billion in 2018/19 has now ballooned to .5 billion in 2021/22 and will continue to increase. This amounts to 0.7% GDP, and is now larger than Long Term Care (LTC) public financing in the Province. Ontario is the only jurisdiction in North America where the Government directly subsidizes electricity prices – indeed, I have a standing public “challenge” for anyone to

Topics:

Edgardo Sepulveda considers the following as important: Canada, carbon pricing, climate change, electricity, energy, environment, Federalism, Ontario, public services, Regulations

This could be interesting, too:

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Joel Eissenberg writes A second nuclear era?

Nick Falvo writes Subsidized housing for francophone seniors in minority situations

Angry Bear writes Associating Microplastics in Mice and Humans

There have been a number of important developments in the Ontario electricity sector since my last update when I summarized my arguments in front of the Ontario Legislature against the proposed Provincial Conservative legislation, now enacted, that eliminated the Provincial Liberal rate-based borrowing scheme to subsidize electricity prices and replace it with Government revenues. The tax-payer financed subsidy of $2.8 billion in 2018/19 has now ballooned to $6.5 billion in 2021/22 and will continue to increase. This amounts to 0.7% GDP, and is now larger than Long Term Care (LTC) public financing in the Province. Ontario is the only jurisdiction in North America where the Government directly subsidizes electricity prices – indeed, I have a standing public “challenge” for anyone to refute my contention that Ontario’s current in-budget end-user price subsidies are the largest on a GDP basis of any medium/large high-income jurisdiction in the world.

But let us set aside that financial disaster for now…. In this post I want to focus on climate, and specifically on GHG emissions and carbon taxes. Despite grave governance errors and poor policy implementation that resulted in Canada’s highest electricity systems costs, one very significant Ontario achievement was that in a short decade it was able to wean itself off coal generation and reduce sector GHG emissions by more than 80%. However, as a result of a series of recent operational and policy decisions, Ontario is in danger of losing some of these hard fought gains.

Gas Electricity Generation

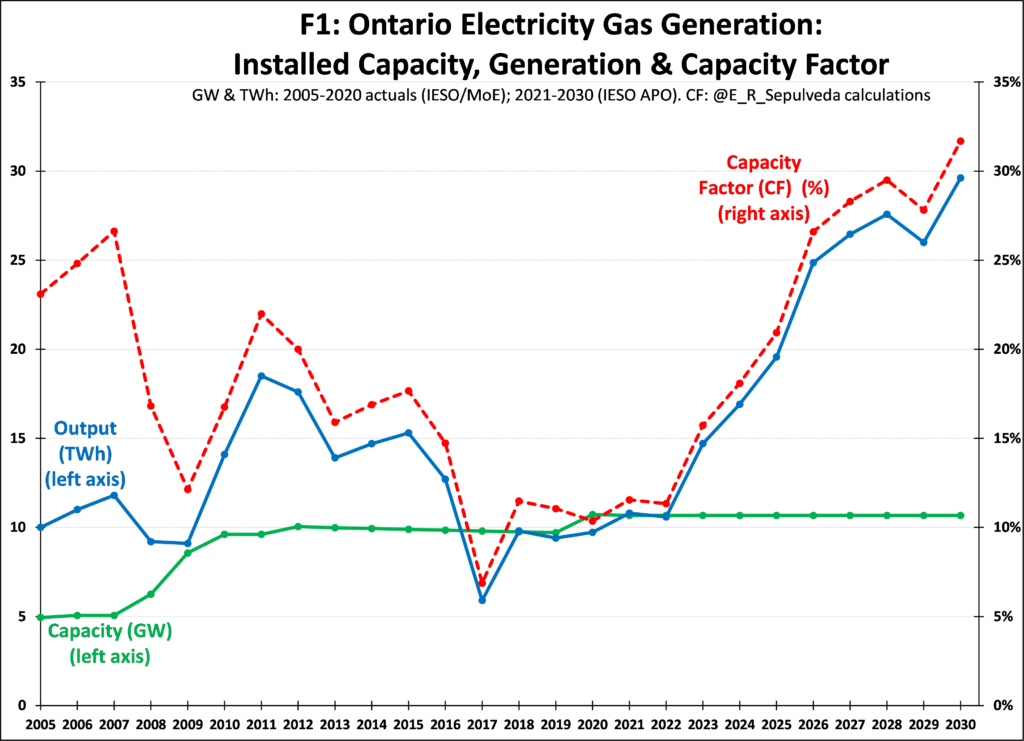

Now that coal generation has been eliminated, the only GHG emitting source in the electricity sector is gas generation. Figure 1 shows the recent development of gas generation in Ontario from 2005 to 2020, and projections to 2030 based on the average of Scenarios 1 and 2 from the Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) 2020 Annual Planning Outlook (APO).

Figure 1 shows that coming out of the 2002 Ontario electricity crisis gas capacity was running at around 5 GW. However, based on a series of Ministry of Energy (MoE) directives, the monopoly government procurement agency, the Ontario Power Authority (OPA) – whose functions have been folded into those of IESO – procured additional gas plants so that capacity doubled from 2007 to 2012, to the current range of between 10-11GW. Output doubled as well, but the average capacity factor (the % of actual vs. potential output if the plant was to run 24/365) remained around 20%. With declining output over the last 5 years, the capacity factor dipped to 10%.

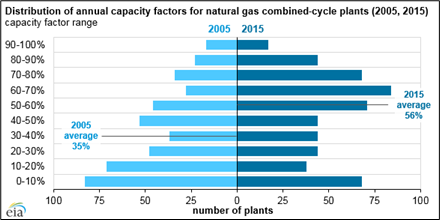

Modern gas plants are designed for and in most other countries run at much higher capacity factors. The unnumbered figure below for the USA as a whole shows the distribution and average capacity factors for gas plants for 2005 and 2015 (increasing from 35% to 56%). From a post-facto perspective it is clear that much, if not most new MOE-centralized procurement of gas generation in Ontario after 2005 was socially unnecessary. As I have argued in the past, this over-procurement resulted in excess capacity and is one of the main drivers of why Ontario has the highest electricity system costs in Canada.

Emissions and Carbon Taxes

Now back to the future… as a result of the SOE generation company, Ontario Power Generation (OPG), deciding not to refurbish its Pickering Nuclear Generating Station (PNGS) and shuttering it in 2024-25, Ontario will need to replace that 20-23 TWh of output to make sure the lights stay on. Figure 1 shows that IESO projects that nearly all of that “missing output” will be taken up by increasing gas output from current gas plants, from the current 10 to 30 TWh by 2030. This will push Ontario gas capacity factors to a “record” 30% by 2030 – still 5% below what the USA achieved in 2005 and 26% below 2015 levels!

Figure 2 shows the emissions impact of this move away from nuclear to gas. GHG emissions from gas move more-or-less in step with output and are expected to be 10 MT or more from 2027-2030, the highest ever in Ontario for gas. And this is with the most modern and efficient gas plants. Figure 2 shows that gas emissions intensity has dropped significantly as newer gas plants have come online, from generally over 0.500 kg/kWh earlier in the period, to an average of 0.408 from 2014 to 2019. In its APO IESO expects this to decrease slightly to 0.390 by 2030.

So why would OPG decide to shutter PNGS? Clearly not for climate reasons, in spite of their net-zero commitment by 2040; under the current Provincial Conservative government OPG went on a buying spree in 2019, purchasing two large existing gas plants and the remaining 50% of two others, so that under its newly-formed subsidiary Atura Power it became the single largest gas generation company in Ontario with 2.7 GW of installed capacity. Adding to that is OPG-held Lennox dual-fuel GS and its shares in other gas generating stations, OPG has a total has installed gas installed capacity of 4.8 GW or nearly half of installed gas capacity in Ontario.

So if the MOE won’t provide climate due diligence over OPG, perhaps Canada’s or Ontario’s carbon tax can come to the rescue and mitigate this climate reversal?

Unfortunately, not as currently planned…..

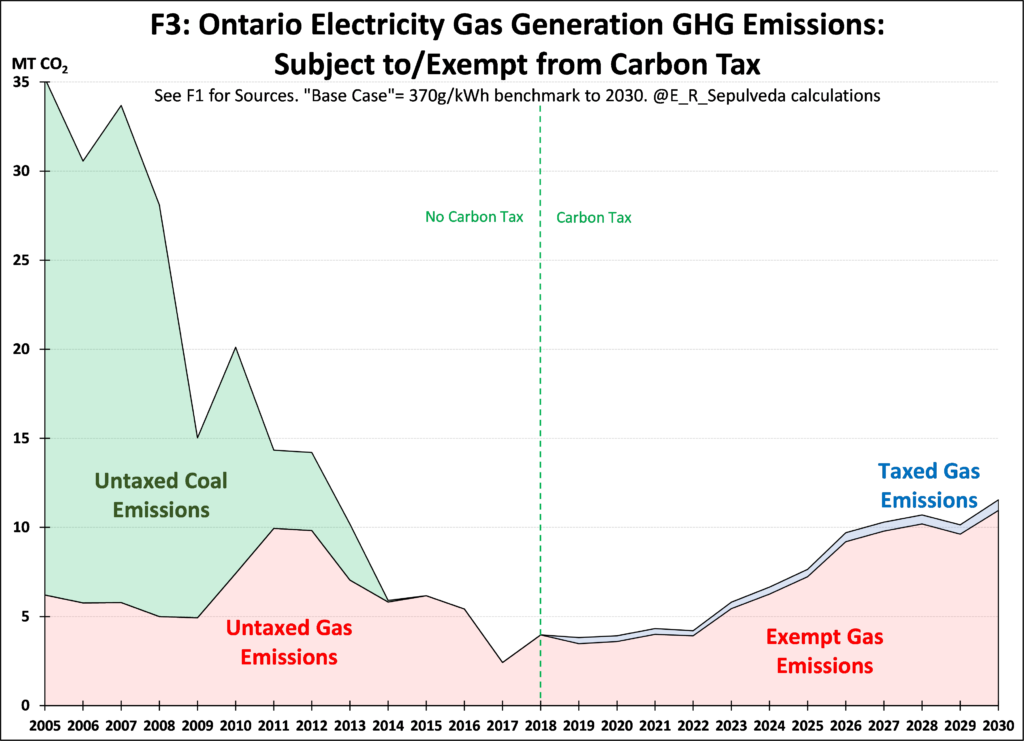

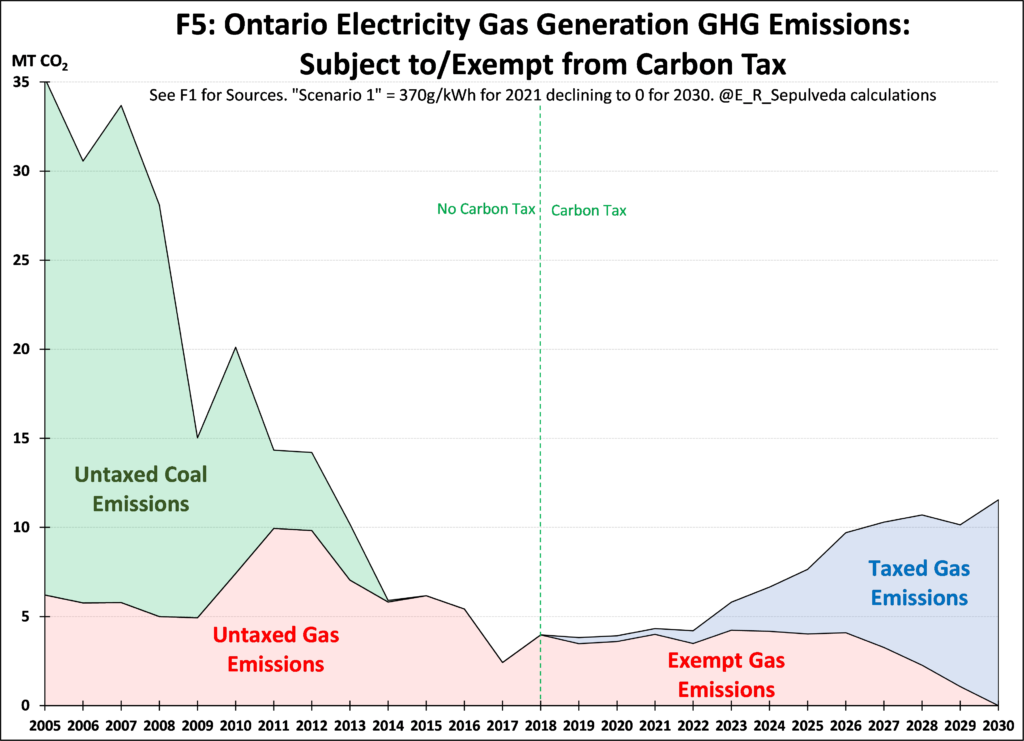

Figure 3 shows the minimal effect that the carbon tax is likely to have. I divide the time line into pre-carbon tax (2005-2018) and post-carbon tax (2019-2030) periods. Data is from the same sources as in Figures 1 and 2. The first period coincides to the coal phase-out, which was done without a carbon tax, which is why I designate the coal and gas emissions as “untaxed”. This is a fundamentally important political-economy consideration – carbon taxes are neither necessary nor sufficient for decarbonization. But public ownership sure helps… All of the coal plants were owned by OPG; the coal phase-out was made more achievable in Ontario because the financial costs were absorbed by OPG under direction of its sole shareholder, the Province. A different set of challenges, including outright monetary compensation, apply when the State decides to shut down privately-owned coal plants in other provinces (e.g. Alberta, Nova Scotia, etc.).

For the second period, in which the carbon tax applies, the only GHG emitter remaining in Ontario is gas. The political economy of carbon taxes in general and how they relate to a federal country such as Canada could be the subject of a whole series of blogs, as could the relative role that carbon taxes could or should play in a decarbonization strategy. For this blog, I will outline that the Federal “back-stop” that would apply in all provinces that the Federal Government does not “certify” is based on end-user fuel-specific levy and a separate large emitter programme, the Output Based Pricing System (OBPS). For example, the former applies to gasoline and diesel bought by consumers to power their cars and natural gas to power their heating furnaces, while the latter applies cement producers and electricity generation plants.

The OBPS is one type of what is generally-referred to as an emission trading system (ETS), sometimes called a “baseline or benchmark and credit” system. The other type of ETS is a “cap and trade” system. This is what had been proposed by the previous Liberal Government in Ontario, which was cancelled by the current Provincial Conservatives, which triggered the back-stop application of the OBPS in Ontario for 2019, 2020 and 2021. As set out below, Ontario will return to a provincial programme, the EPS in 2022. This yo-yo policy is in contrast with Quebec and BC that have had their systems in place for over a decade that have been already “certified” by the Federal Government.

There are number of policy reasons why a jurisdiction would choose to impose either an “end-user” fuel levy and/or an “intermediate” ETS. One of the reasons Governments implement ETS is that their design features make them very flexible to take into account local conditions and preferences. One aspect is degree of coverage, which I’ll cover further below. Another aspect relates to “carbon leakage”, which is the idea that in a globalized economy, over-taxation in jurisdiction A may reduce emissions in A, but could increase emissions in lower-taxation jurisdiction B. Hence in “trade exposed” sectors, ETS schemes typically have “benchmarks” or “performance” levels under which emissions are exempt. These levels are typically set at 80% to 95% of sector averages, so that only 20% or 5% of emissions would be taxed, respectively. The idea here is that the large emitters are still incented at the margin to reduce their emissions, but are not “over taxed” and thus made uncompetitive.

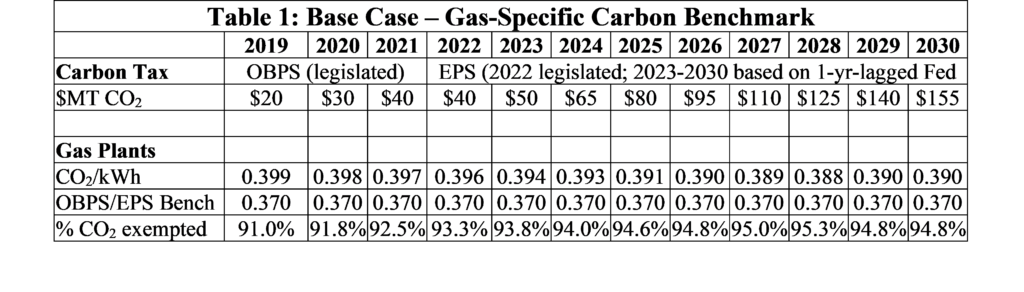

Electricity generation is not a “trade exposed” sector, yet the OBPS was designed with a fuel-specific benchmark of 370 g/kWh, exempting about 91% of gas emissions in Ontario, as set out in Table 1, which also includes the data included in Figure 3. The technical reasons behind treating the electricity sector as a “trade exposed” has never been specifically explained by the Federal Government – my take is that it constitutes a form of “lowest common denominator” necessary to make the back-stop less unacceptable to Provinces with high emission electricity sectors. Last year the Federal Government “certified” Ontario’s proposed ETS, the Emission Performance Standard (EPS), which is now scheduled to take over from the OBPS in Ontario beginning January 2022. The EPS is a carbon copy (pardon the pun) of the OBPS as it relates to the electricity sector, with a one-year lag in the size of the carbon tax.

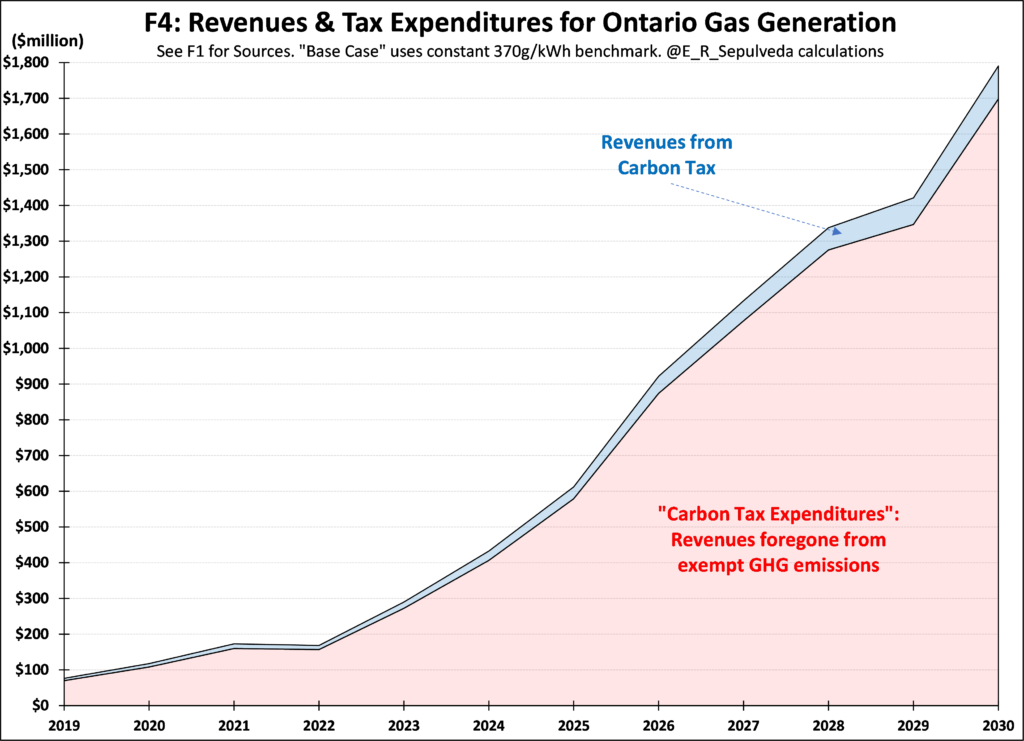

The Base Case presented in Figure 3 and Table 1 would not only be a climate failure, it would also be a financial failure. Figure 4 shows the estimated proceeds from the application of the carbon tax under the Base Case, collecting only about $90 million in 2030, while exemption $1,700 in emissions. In fiscal economics we call this “tax expenditures” the dollar amount of forgone revenues from the application of exemptions or deductions, commonly referred to as “loopholes”.

Alternative A: Gradual reduction of the Exemption

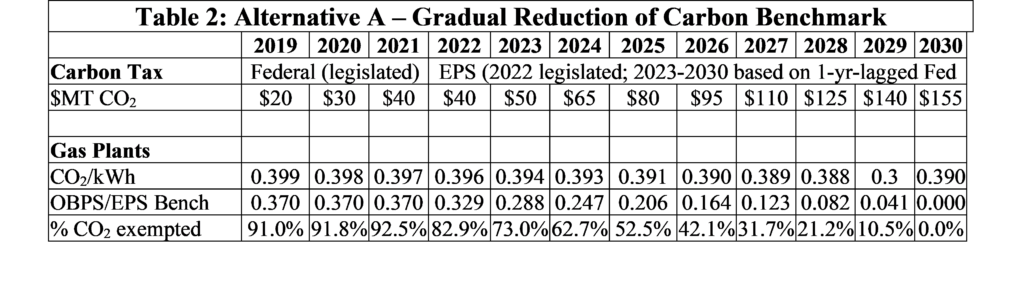

What would happen if the MoE were to decide to gradually eliminate the current exemption? Could be in 2023 or in 2030 or some other time. Table 2 shows the static results of Alternative A which would lower the 370 g/kWh benchmark starting in 2022 to zero in 2030 , thus reducing exempted emissions to 0% by that same date.

Figures 5 and 5 are the Scenario A equivalents of the Base Case Figures 3 and 4, showing the evolution of taxed and exempt emissions, and the taxation revenues and tax expenditures, respectively.

Carbon Coverage – Base Case and Alternative

For carbon taxes to play their theorical role of revealing socially-optimal prices, coverage should be as broad as possible, including in the electricity sector. This is not the case for the OBPS, which only covers fossil fuel generation and has a fuel-specific benchmark. This means that non-fossil generation, including nuclear, wind and solar, are uncovered and therefore are not eligible to receive credits for emissions under the relevant benchmarks. ETS schemes do not have to be designed in this manner – the recently-revised TIER in Alberta covers all generation technologies, resulting in an even level playing field.

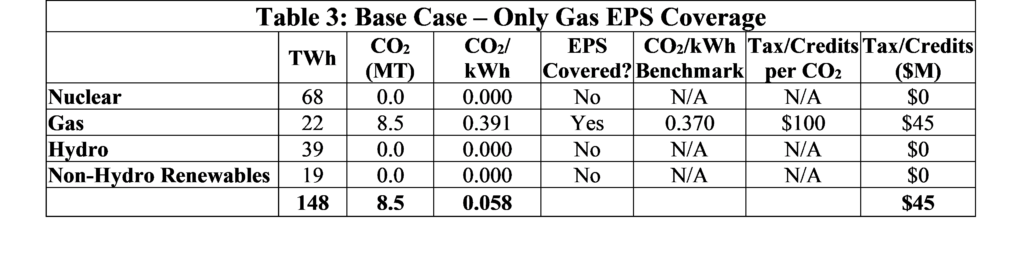

Table 3, which is the Base Case, is how the EPS is currently designed. For illustrative purposes, I have calculated a “typical” forward-looking year, based on the average 2022-2030 period. This includes a period average carbon tax of $100 which is only applicable to gas generation. Table 3 shows that the EPS only covers gas, which has a benchmark exemption of 0.370 CO2 kg/kWh, average emission intensity of 0.391 and output of 22 TWh. The resulting payment in carbon taxes is $45 million for that average/typical year. The formula is (0.391 – 0.370) * 22 * $100 = $45 million.

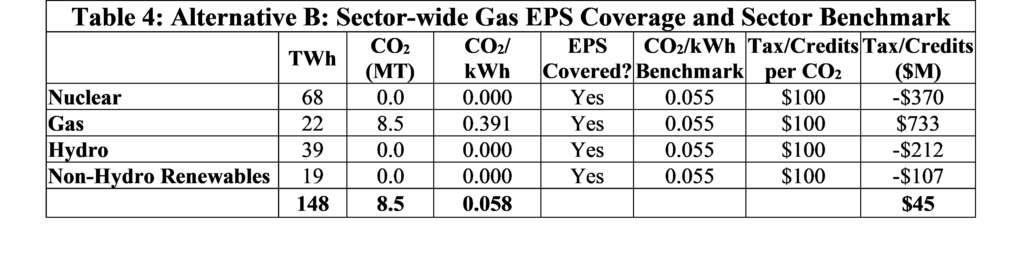

In contrast, Table 4, which is the Alternative B, is the scenario under which all generation technologies are covered by the EPS, as is the case in Alberta under the TIER. The EPS benchmark could stay the same at 370 g/kWh, but that would create a surplus of sector compliance units (credits). This is not necessarily a problem if other covered sectors in the economy are in deficit, so that as whole the covered sectors are in rough balance. But for this scenario I want to set the benchmark to roughly balance the net tax/credits, relative to the Base Case. I do this by applying the principle of setting the performance level at between 80-95% of average sector emissions intensity. Specifically I set the standard at 0.055 in Table 4 so as to have the same net tax/credits as the Base Case ($45 million). Other alternatives are of course possible.

Using the same formula we can calculate what would be the results of this Alternative. One difference would be much higher payments by gas plants. On the other hand, low and zero emission generation would now receive credits. Overall, the net proceeds of the scheme would remain the same. The value of the credits would of course be determined based on trading, but for simplicity I set them in Table 4 to have the same value of as the corresponding carbon tax.

In comparing these two Tables it is clear from Table 3 that only covering fossil fuel generation sends the wrong climate investment signals with respect to electricity generation. The difference due to carbon prices between gas and hydro, for example is only $0.0021/kWh. In contrast, Table 4 levels the playing field by ensuring that zero-emissions technologies are credited relative to gas generation. The difference due to carbon prices between gas and nuclear, for example, increases by nearly 20 times, to $0.0391/kWh. Would OPG have made the same decision not to refurbish PNGS and buy nearly 3GW of gas plants if it had faced these set of relative prices reflecting carbon costs?

Further layers of complexity could be added to Table 4 to take into account price, cost and subsidy levels. For example, the Alberta TIER scheme, some non-hydro renewables that are already subsidized are therefore not eligible for carbon credits.

Concluding Thoughts

The Provincial Conservatives touted the EPS as a “made in Ontario” solution to climate change. As it relates to the electricity sector, the EPS, when in comes into force in January 2022, is a continuation of the Federal Liberal non-solution that is the OBPS.

As proposed, the EPS is fatally flawed in two respects. One, by only covering non-fossil generation technologies it tilts the playing field in favour of fossil generation. Two, it exempts 91% or more of fossil generation in Ontario.

The MoE is currently consulting on a series of technical amendments to the EPS for it to replace the OBPS and come into full force in Ontario in January 2022. Comments are open until July 11, 2021. This includes “aligning the performance standard for electricity generation with the Federal OBPS standard to provide greater stability and reduce administrative complexity in the electricity market by: adjusting the Ontario performance standard for all fossil fuel fired electricity generation from 420 to 370 CO2e/GWh”. For all the climate reasons above, I will be proposing that the exemption should be eliminated in a step-wise matter, including because the electricity sector does not meet the criteria of a “trade-exposed” sector for which such exemptions are designed.