I was invited to speak at the International Conference on ‘Liberalism, Marxism, Study of Realism, Gandhism and Communism’, organised by FARAK in India. The subject of my speech is ‘Marxism and its contemporary relevance’. The transcript of my speech follows. FARAK international conference ‘Liberalism, Marxism, Study of Realism, Gandhism and Communism’ ‘Marxism and its contemporary relevance’ Stavros Mavroudeas Professor of Political Economy Panteion University, Athens, Greece e-mail: [email protected] What is Marxism and why is relevant today In 1989, after the fall of the Eastern bloc, mainstream pundits professed the death of Marxism. However, not long since, around the 2008 global capitalist crisis this mainstream belief was shaken. Even die-hard mainstream voices

Topics:

Stavros Mavroudeas considers the following as important: dialectical materialism, Historical Materialism, Marxism, Mavroudeas, profit, relevance, Εισηγήσεις σε επιστημονικά συνέδρια - Papers in academic conferences

This could be interesting, too:

Stavros Mavroudeas writes Is Neoliberalism still the dominant economic paradigm in the West today? – S.Mavroudeas

Stavros Mavroudeas writes Once again on the shadow playing of Greek capitalism

Joel Eissenberg writes Pete Hegseth knows nothing about Marxism

Stavros Mavroudeas writes COVID-19 Pandemic and Vaccine Imperialism – Review of Radical Political Economics

I was invited to speak at the International Conference on ‘Liberalism, Marxism, Study of Realism, Gandhism and Communism’, organised by FARAK in India.

The subject of my speech is ‘Marxism and its contemporary relevance’.

The transcript of my speech follows.

FARAK international conference

‘Liberalism, Marxism, Study of Realism, Gandhism and Communism’

‘Marxism and its contemporary relevance’

Stavros Mavroudeas

Professor of Political Economy

Panteion University, Athens, Greece

e-mail: [email protected]

What is Marxism and why is relevant today

In 1989, after the fall of the Eastern bloc, mainstream pundits professed the death of Marxism.

However, not long since, around the 2008 global capitalist crisis this mainstream belief was shaken. Even die-hard mainstream voices (like the FT and the Economist) professed that Marx is more relevant than ever today. Of course, they gave a distorted picture of Marx and Marxism. Nevertheless, the ‘death of Marxism’ argument was buried for good.

The advent of the current COVID-19 health-cum-economic crisis reverberated even more strongly the contemporary relevance of Marxism.

But what gives Marxism this enduring analytical and practical power?

The answer lies in his ‘DNA’. Marxism is an entity comprising of (a) a worldview, (b) a socio-economic analysis and (c) a guideline for social praxis.

Marxism’s worldview

The essence of Marxism’s worldview is the very realistic proposition that our world is material, conflictual and dynamic.

- Material because it is the matter (rather than some metaphysical mind) that forms our world.

- Conflictual because contradictions (between social classes, opposing interests etc.) are the rule.

- Dynamic because the struggle between the opposing sides of these contradictions generates change.

This is the old philosophical tradition of dialectics. Marx and Engels based this perspective on material conditions (rather than on idealist principles as for example in Hegelian idealist dialectics).

Hence, Marxism conceives the world as a material entity which is riddled with contradictions (and not harmony) and is prone to changes.

Marxism’s world view is organized on the basis of two intertwined theoretical sets: Dialectical Materialism and Historical Materialism.

Dialectical Materialism

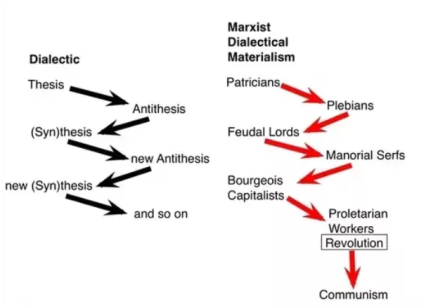

Dialectical Materialism offers the methodology to understand our world. It is founded on the old dialectical scheme of thesis – antithesis – synthesis. This scheme signifies that out of the struggle between opposing sides (thesis and antithesis) a new situation will emerge (synthesis).

Among the many other features of the dialectical materialist analysis two have a prominent role and are particularly pertinent for comprehending the contemporary world.

The first feature is the distinction between appearance and essence. Its situation has an external appearance (the way it is presented in everyday life). But beneath it is hidden an essence; that is a system of generic relations that may not be viewed with a naked eye, but it dictates the way things evolve. For understanding the true condition of things, the human theory must move beyond the realm of appearances and discover the hidden essence of things. According to Marx’s very accurate dictum ‘all science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided’. The essence represents the general, generic elements and their concomitant laws of motion of a thing and/or a situation. Thus, it represents its general characteristics or, in dialectical materialist terms, its abstract dimension. The appearance is the modification of this general character with specific and special (for each particular case) characteristics. Hence, the appearance belongs to the level of the concrete.

| Appearance | Essence |

| concrete | abstract |

The second crucial feature is the method of abstraction. It follows from the previous feature. In order to understand the world, we have to proceed beneath the level of the appearances and discover the hidden but governing level of essence. Science should do this through the method of abstracting from special characteristics (which are of a lesser importance), concentrate on the few basic aspects and then dig beneath them to discover the hidden essence.

abstract concrete

Historical Materialism

Historical Materialism is the application of the dialectical materialist perspective in comprehending the human history. Marxism breaks radically from pre-existing conceptions of history as the result of the impact of ideas that were to effect changes in a society. For Marxism, ideas stem from material conditions. At the heart of material conditions is the economy; that is the system through which the humankind gets the necessities for its subsistence. This has been characterized, by friends and foes, as economic determinism. It is indeed economic determinism (as even Bill Clinton recognized that ‘It is the economy stupid’ that matters). But, contrary to the various anti-determinists, it is a determinism that (a) permits degrees of freedom and (b) recognizes feed-back effects. Hence, it is not a mechanistic determinism, as they erroneously clamour. In more strict Marxist terms, the economic relations are the base on which the superstructure (the rest of the social relations) is erected.

Contradictions – that is the struggle between opposing sides – in class-divided societies takes the form of class struggle between social classes. The primary field of this class struggle is the economy, but it subsequently spills over to the rest of social relations (which in turn affect the economy through feedback circuits).

Then Marxism explains the evolution of human societies through a stages of history theory. Human societies are organized on the basis of modes of production (MoP – that is configurations of socio-economic relations between different classes). Thus, different modes of production are recognized (primitive communal societies, slavery, feudalism, capitalism etc.). Each MoP has exhausted its life cycle and is ready for substitution by another MoP once it can no longer develop the forces of production (FoP – that is expand the well-being of societies).

Marxism’s socio-economic analysis

The world’s materiality rests primarily on the economy. For this reason, Marxism accurately profess the primacy of the economy over the rest of the social relations. Thus, Marxism’s second fundamental axis is his system of political economy. It consists of the Labour Theory of Value (LTV) and the Theory of Surplus-Value.

Labour Theory of Value

This theory regards human labour as the sole creator of wealth. Human labour is the only active component of the production process and the one that sets in motion the other FoP (means of labour etc.). Without human intervention no wealth-production can take place. Consequently, in capitalism (capitalist commodity production), where almost all goods become commodities, the amount of labour spent over the production of each commodity is its value. This (labour) value passes through a series of transformations (as it passes from the sphere of production to the spheres of circulation and distribution) and it is ultimately expressed as (monetary) price. Hence, value determines price but the latter – contrary to D.Ricardo – almost never coincides with its determining value; it rather fluctuates around it. This is the famous Law of Value:

value determines price

Marx formulated this conception through his Value Theory of Abstract Labour (that is a social conception of labour), as distinct from Ricardo’s (and the majority of Classical Political Economy) Value Theory of Embodied Labour (that is a technical conception of labour). Also contrary to Ricardo, value determines price but (a) through an indirect mechanism passing through different spheres (Prices of Production) and (b) at a subsequent phase prices feed-back on values.

Theory of Surplus-Value

This is the theory that explains how exploitation takes place in the capitalist system. It is based on the valid assumption that what it is bought and sold in the labour market is not the labour performed but the ability to perform labour (labour-power). This assumption grasps very accurately the fact that what a capitalist buys are hours of labour under his command and not the actual labour performed. The capitalist pays to the labourer a certain amount (value of labour-power). Then, the capitalist implements his managerial prerogative and is able to extract from the labourer’s work more value than what he has initially paid him. This is called surplus-value, it is unpaid labour and it is transformed in the capitalist’s profit.

It is worth noting that no other economic theory (Neoclassical, Keynesian etc.) can offer a different coherent explanation of the capitalist’s profit.

Subsequently, Marxism argues that capitalism is a socio-economic system organized around the extraction of profit (profit motive). This is again a very realistic assumption that no other economic theory can offer a satisfactory alternative.

From the rich and sophisticated Marxist economic analysis two elements are especially important.

The first element is that the capitalist system is riddled with internal contradictions. A consequence of these contradictions is the regular appearance of economic crises. Marxism, as opposed to mainstream Economics, has a very developed and meticulous theory of economic crises. The basis of the Marxist theory of economic crises is the famous Law of the Tendency of the Profit Rate to Fall (LTPRF). The gist of this argument is that capitalists by competing among themselves for greater profits ultimately lead the system to overaccumulation (that is expansion beyond its realistic dimensions) and thus to a falling rate of profit. This falling profitability tendency, once surpassing certain definite levels, leads to economic crises (that is the collapse of normal functioning of the system and the reduction of the GDP). In a nutshell, this conception argues that the ‘success’ of the system leads to its ‘failure’.

Relentlessly, Marx emphasises this self-destructive force built into the process of capitalist development:

‘And how does the bourgeoisie get over these crises? On the one hand, by the enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces; on the other, by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones. That is to say, by paving the way for more extensive and more destructive crises, and by diminishing the means whereby crises are prevented.’

The second important element of Marxist economic analysis is that as the capitalist system ‘grows old’ (that is it fails to expand the FoP and becomes an obstacle to their further development), then it increases the exploitation of the toiling masses. This takes the form of relative (but also absolute in several cases) immiseration of the popular classes. In stricter terms, this explains the increase of economic inequalities and poverty in contemporary capitalism.

Marxism’s guideline for social praxis and change

Based on his worldview and his socio-economic analysis, Marxism offers his guideline for social praxis. It argues that once a socio-economic system is exhausted it is futile to try to reform it. Thus, it is necessary to remove it and substitute it with a better one. This has happened in the past with the succession from pre-capitalist socio-economic systems to the capitalist socio-economic system. Hence, Marxism pivot for social praxis is the societal change.

This societal change does not take place smoothly and peacefully as vested dominant interests and social classes do not relinquish their grip on society. Thus, societal change comes through class struggle:

‘The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles’

(K.Marx)

In the case of the capitalist system, class struggle takes place on the basis of the antagonistic relationship between its two main classes: labour (the creator of social wealth) and capital (the appropriator of the greater part of social wealth). Marxism argues that labour (the working class) is the instigator of societal change towards a more just and equitable socio-economic system: socialism (and ultimately communism). Class struggle by labour (and the rest of the allied with-it popular classes) should not try to reform the system as this is futile. Instead, it should follow the strategic aim of overthrowing the whole system. This strategic aim is organized at the tactical level with the everyday struggles for ameliorating the working and living conditions of the toiling classes.

The contemporary relevance of Marxism

Marxism’s ‘DNA’ (his worldview, socio-economic analysis and guideline for social praxis) gives him his analytical and practical superiority and explains his contemporary relevance.

The recurrence of economic crises during the recent decades (e.g. 2008, 2020) emphasises Marxism’s superiority against mainstream Economics. His focus on economic crises makes Marxism better equipped to understand bot the existence and the recurrence of this phenomenon; whereas mainstream Economics simply lack a general theory of crisis or hve a very weak one (in the case of Keynesianism).

Similarly, the increase of inequalities and poverty in contemporary capitalism prove the contemporary relevance of Marxism. Again, mainstream Economics fail to offer a convincing alternative perspective.

But also, at a deeper epistemological level, Marxist materialist dialectics and their notion of contradiction prove particularly apposite in understanding the contemporary world that is riddled with conflicts and antagonisms.