From David Ruccio From the beginning, mainstream macroeconomics has been a battleground between the visible and the invisible hand. Keynesian macroeconomics, represented on the left-hand side of the chart above, has an aggregate supply curve with a long horizontal section at levels of output (Y or real GDP) below full employment (Yfe). What this means is that the aggregate demand determines the actual level of output, which can be and often is at less than full employment (e.g., when AD falls from AD1 to AD2, output to Y1, and prices to P2), with no necessary tendency to return to full employment and price stability. Therefore, according to Keynesian economists, the visible hand of government needs to step in and, through a combination of fiscal and monetary policy, move the economy

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

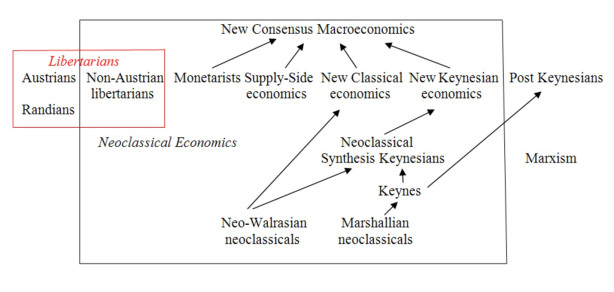

From the beginning, mainstream macroeconomics has been a battleground between the visible and the invisible hand.

Keynesian macroeconomics, represented on the left-hand side of the chart above, has an aggregate supply curve with a long horizontal section at levels of output (Y or real GDP) below full employment (Yfe). What this means is that the aggregate demand determines the actual level of output, which can be and often is at less than full employment (e.g., when AD falls from AD1 to AD2, output to Y1, and prices to P2), with no necessary tendency to return to full employment and price stability. Therefore, according to Keynesian economists, the visible hand of government needs to step in and, through a combination of fiscal and monetary policy, move the economy toward full employment (at Yfe) and stable prices (at P1).

Neoclassical macroeconomists, like their classical predecessors, have a very different view of the macroeconomy, which is represented on the right-hand side of the chart. They start with a vertical aggregate supply curve at a level of output corresponding to full employment. Therefore, according to their theory—often referred to as Say’s Law or “supply creates its own demand”—aggregate demand does not determine the level of output; instead, it determines only the price level. Thus, for example, if aggregate demand falls (e.g., from AD1 to AD2), output does not change (it remains at Yfe)—only the price level falls (from P1 to P2). On the neoclassical view, the invisible hand of the market maintains full employment (through the labor market) and reverses price deflation (through the so-called real-balance effect) by boosting aggregate demand (back to AD1 from AD2).

Anyone who has read or heard the intense debates concerning capitalism’s recurrent crises, recently and going back to the 1930s, knows that there are significant theoretical and policy differences between Keynesian and neoclassical macroeconomists. For example, Keynesians focus on uncertainty (especially the uncertain knowledge of investors) and the important role of government (especially fiscal) policy, while neoclassicals emphasize the supply side (especially the role of correct “factor prices,” particularly wages) and the necessity of getting government out of the way of markets (relying, instead, on rules-driven monetary policy).*

But there are equally significant similarities between the two approaches. For example, both Keynesian and neoclassical economists tend to blame economic downturns on exogenous events. There is nothing in either theory that recognizes capitalism’s inherent instability. Instead, mainstream macroeconomists of both stripes direct their attention to equilibrium outcomes—of less-than-full employment in the case of Keynesians, of full employment for neoclassicals—such that only something outside the model can shift the underlying variables and cause the economy to move away from equilibrium. That’s why neither group was able to foresee the crash of 2007-08, let alone the other eighteen recessions and depressions that have haunted capitalism during the past century. Their theories literally don’t include the possibility, endogenously created, of capitalism’s ongoing crises.

There’s another, perhaps even more important, similarity I want to draw attention to here: their shared utopianism. The premise and promise of both Keynesian and neoclassical macroeconomics is that, with the appropriate institutions and policies, capitalism can be characterized by and should be celebrated for achieving full employment and price stability. Those are the shared goals of the two theories. And their criteria of success. Thus, each group of macroeconomists is able to claim a position of expertise when the actual performance of the economy achieves, or at least moves closer and closer to, a utopia characterized by levels of output and a price level that corresponds to full employment and price stability.

It is precisely in this sense that the economic utopianism of mainstream macroeconomics conditions and is conditioned by an epistemological utopianism. Because they know how the macroeconomy works—because of their theoretical and modeling certainty—both Keynesian and neoclassical macroeconomists claim for themselves the mantle of scientific superiority. These are the lords of macroeconomic policy, domestically and internationally, moving back and forth among their positions as academics, corporate advisers, and policy experts. Hence the persistent claim on both sides that, if only the politicians and policymakers listened to them and adopted the correct economic policies, everything would be fine. Not to mention the ongoing complaints, again on the part of both groups of mainstream macroeconomists, that their advice has been ignored.

That, of course, is where the critique of mainstream macroeconomics begins—with a radically different utopian horizon. When the explanations and policies of either side are said to have failed, there’s a shift to the opposing viewpoint. Thus, for example, neoclassical macroeconomics held sway (in the United States and elsewhere) in the run-up to the crash of 2007-08—just as it had in the years preceding the first Great Depression. Leading macroeconomists and their students had moved away from and largely ignored anything that had to do with Keynesian macroeconomics (including, most notably, Hyman Minsky’s writings on financial instability). Then, of course, the tables were turned and at least some mainstream macroeconomists went back and discovered (many for the first time) the theories and policies associated Keynesian tradition.

It’s a familiar back-and-forth pendulum swing that we’ve seen in many other countries, in other times. From neoclassical free markets and deregulation to government stimulus and one or another form of reregulation—and back again. But we also need to recognize that the failures of mainstream macroeconomics, when examined from an alternative perspective, have actually succeeded. As I wrote back in 2010, the failure of neoclassical macroeconomists were apparent to many: they

failed to see the onset of the current crises; they have had little to offer in terms of understanding how the crises occurred even after the fact; and they certainly haven’t had much in the way of good policy advice to solve the problems of unemployment, poverty, and inequality. . .

On another level, mainstream economists have succeeded. Not only have they maintained their hegemony within the discipline; their models and policy advice have kept the discussion confined to tinkering with the existing set of capitalist institutions. In terms of policy: a bail-out of Wall Street and a mild set of financial reforms, a small stimulus program, and an expansionary monetary policy. And intellectually: a rediscovery of Keynes and an allowance of behavioral approaches to finance. They haven’t proposed even the public works programs and financial reorganization of the New Deal, let alone an honest debate about capitalism itself.

In this sense, the continued failure of mainstream economists has become a success for capitalism.

That’s why we need to question the shared utopianism of the two sides of mainstream macroeconomics. What has gone missing from much of the current debate, even outside the mainstream, is that full employment and price stability are consistent with the worst abuses of contemporary capitalism. As David Leonhardt recently explained,

The headlines may talk about growth, but we are living in a dark economic era. For most families, income and wealth have stagnated in recent decades, barely keeping pace with inflation. Nearly all the bounty of the economy’s growth has flowed to the affluent.

And if you somehow doubt the economic data, it’s worth looking at the many other alarming signs. “Deaths of despair” have surged. For Americans without a bachelor’s degree, one social indicator after another — obesity, family structure, life expectancy — has deteriorated.

There has been no period since the Great Depression with this sort of stagnation. It is the defining problem of our age, the one that aggravates every other problem. It has made people anxious and angry. It has served as kindling for bigotry. It is undermining America’s vaunted optimism.

In fact, an even stronger argument can be made: the various attempts to move the economy toward full employment and price stability have created the conditions whereby capitalism has both broadened and deepened its presence and made the lives of the vast majority of people even more unstable and insecure.

The utopianism of mainstream macroeconomics represents a dystopia for “most families” attempting to survive within contemporary capitalism.

What’s left then is a critique of the assumptions and consequences of mainstream macroeconomics—of both neoclassical and Keynesian economic theories. The goal is not just to tinker with the theories (e.g., by bringing finance into the discussion) or the policies (such as technocratic changes to the tax code and raising the level of productivity). Recognizing how narrow the existing discourse has become means we need to question the entire edifice of mainstream macroeconomics, including its utopian promise of full employment and price stability.

Only then can we begin to recognize how bad things have gotten under both the successes and failures of mainstream macroeconomics and to imagine and invent a radically different set of economic institutions.

That’s the only utopian horizon currently worth pursuing.

*Throughout I refer to two groups of Keynesian and neoclassical macroeconomists. But, of course, both theories have changed over time. Today, the two opposing sides of mainstream macroeconomics are constituted by new Keynesian and new classical theories, with increased attention to the “microfoundations” of macroeconomics. The former emphasizes market imperfections (such as price stickiness and imperfect competition), while the latter dismisses the relevance of market imperfections (and emphasizes, instead, flexible prices and rational expectations). And then, of course, there’s the ever-shifting middle ground, which is the basis of a macroeconomics according to which new Keynesian and new classical are both valid, at different points in the business cycle. Like the earlier neoclassical synthesis, the middle ground of “new consensus macroeconomics” is the approach presented to most students of economics.