From David Ruccio In a 1999 interview with Fortune, legendary investor Warren Buffett coined the term “economic moats” to sum up the main pillar of his investing strategy. He described it like this: The key to investing is not assessing how much an industry is going to affect society, or how much it will grow, but rather determining the competitive advantage of any given company and, above all, the durability of that advantage. The products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors. The idea of an economic moat, with Buffett’s endorsement, has picked up steam since the article. Morningstar, an investment research firm, created an index that tracks companies with a wide economic moat in order to see if Buffett’s theory holds

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

In a 1999 interview with Fortune, legendary investor Warren Buffett coined the term “economic moats” to sum up the main pillar of his investing strategy. He described it like this:

The key to investing is not assessing how much an industry is going to affect society, or how much it will grow, but rather determining the competitive advantage of any given company and, above all, the durability of that advantage. The products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors.

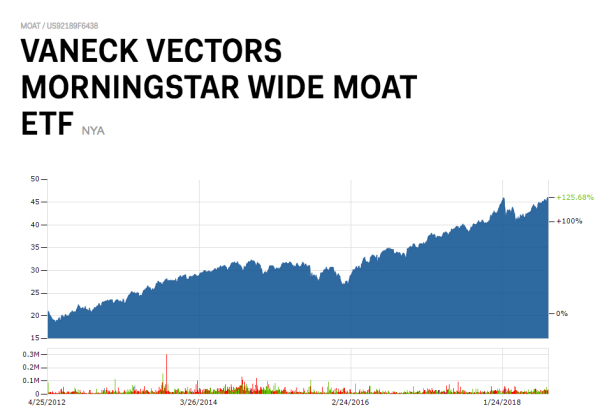

The idea of an economic moat, with Buffett’s endorsement, has picked up steam since the article. Morningstar, an investment research firm, created an index that tracks companies with a wide economic moat in order to see if Buffett’s theory holds water. In 2012, VanEck, a money manager, created an exchange-traded fund called “MOAT” that would track Morning Star’s economic moat index.

And it works! Since 2012, VenEck’s Wide MOAT fund has beaten the Standard & Poor’s Index: it’s up 125.68 percent compared to the S&P’s 108 percent.

But what’s true for the individual investor does not hold for the U.S. economy as a whole. That’s because corporations with a Buffet moat around them are only managing, for a time, to capture portions of the surplus produced and appropriated elsewhere. It’s a rent—thus, of course, justifying the use of a feudal concept to characterize an investment strategy within contemporary capitalism.

Of course, the U.S. economy is not feudal (at least, for the most part). Instead, it is based on capitalism. And what’s important about American capitalism is the gap between workers’ wages and the total value they produce, which is profits—a portion of which is distributed in the form of dividends.

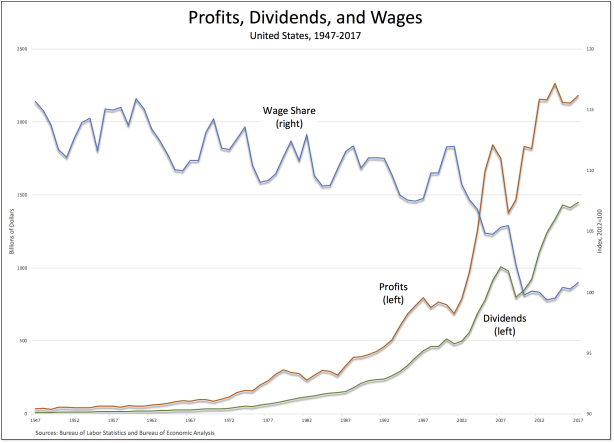

As is clear from the chart above, over the course of the past decade both corporate profits (the red line) and dividends to shareholders (the green line) have rebounded spectacularly while the share of national income going to labor (the blue line) has fallen precipitously and remained very low. That’s the case during the so-called recovery from the crash of 2007-08 as well as the 15 or so years prior to the crash.

So, the comparison between feudalism and capitalism is perhaps even more apt than Buffett and other investors are willing to admit: in both cases, the surplus labor pumped out of the direct producers—serfs then, wage-laborers now—is appropriated—in the form of feudal rents or capitalist profits—and is then distributed to still others—to other religious and secular lords or other capitalists and equity owners.

And the result is exactly the same: a growing gap between the small group of gangsters at the top and everyone else.