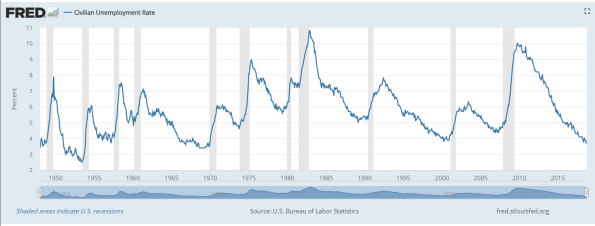

Graph 1. Unemployment in the USA, % of the labor force, monthly data. One of the central and most pressing questions of macro-economics is how to estimate and explain unemployment. Thomas Sargent, card-carrying member of the neoclassical cabal and winner of the ‘Sveriges Riksbank Prize In Economic Sciences In Memory Of Alfred Nobel’ (SRPIESIMOAN) just made a shot at it. A somewhat Marxist shot, as far as I’m concerned. Which, considering the hard core neoclassical nature of the rest of the work of Sargent, is quite surprising. What’s the case? Unemployment as we measure it is a cyclical variable (graph 1). The increases of unemployment coincide perfectly with the downswings of the business cycle which are measured using methods pioneered by Wesley Mitchell (the grey bars in graph 1).

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Graph 1. Unemployment in the USA, % of the labor force, monthly data.

One of the central and most pressing questions of macro-economics is how to estimate and explain unemployment. Thomas Sargent, card-carrying member of the neoclassical cabal and winner of the ‘Sveriges Riksbank Prize In Economic Sciences In Memory Of Alfred Nobel’ (SRPIESIMOAN) just made a shot at it. A somewhat Marxist shot, as far as I’m concerned. Which, considering the hard core neoclassical nature of the rest of the work of Sargent, is quite surprising. What’s the case?

Unemployment as we measure it is a cyclical variable (graph 1). The increases of unemployment coincide perfectly with the downswings of the business cycle which are measured using methods pioneered by Wesley Mitchell (the grey bars in graph 1). Also, declines take much more time than the increases. The cyclicality of unemployment is a problem for neoclassical macro-economics. Neoclassical macro has a binary view of human time: you’re either at work in the market (pain) or you’re enjoying leisure (pleasure). Unpaid household work or not having a job but seeking one are as a (common) rule not acknowledged as separate activities. Yeah, there are exceptions to this rule. But your typical neoclassical macro ‘DSGE’ model does not incorporate such exceptions. Which means that the models can’t explain unemployment simply because unemployment is not part of the models. ‘Unemployment is leisure’. I’m not kidding. Another recipient of the SRPIESIMOAN, Robert Lucas, as well as Edward Prescott (a winner too) and Mortensen and Pissarides (also SRPIESIMOAN winners) often or, in the case of Prescott, always denote unemployment with the word: ‘leisure’. This modeling strategy of course does not make unemployment go away. And it doesn’t make it less cyclical. Or less important. Or less scarring, scaring and depression inducing. And especially after 2008 it became urgent to adapt the neoclassical model to the variable that could not be ignored anymore. Thomas Sargent (together with Lars Ljundqvist) tried to make sense of it all. Reading their work, it reminded me of something I had read not too long ago, ‘The processes involved in business cycles’ by Wesley Mitchell (1927). About Marx, Mitchell writes:

The most vigorous attempt to prove that crises are a chronic disease of capitalism, however, was that made by Rodbertus and elaborated by Karl Marx. The germ of this theory also is found in Sismondi and Robert Owen. Wages form but a fraction of the value of the product and increase less rapidly than power to produce. Since the masses dependent upon wages constitute the bulk of the population, it follows that consumers’ demand. cannot keep pace with current supply in seasons when factories are running at full blast. Meanwhile the capitalist-employers are investing their current savings in new productive enterprises, which presently add their quotas to the goods seeking sale. This process of over-stocking the market runs cumulatively until the time comes when the patent impossibility of selling goods at a profit, or even at cost, brings on a crisis.

Now,Sargent and Ljundqvist):

For any model with a matching function, to arrive at the fundamental surplus take the output of a job, then deduct the sum of the value of leisure [he means wage costs, M.K.] , the annuitized values of layoff costs and training costs [labor costs too, in modern accounting, M.K.] and a worker’s ability to exploit a firm’s cost of delay under alternating-offer wage bargaining, and any other items that must be set aside. The fundamental surplus is an upper bound on what the “invisible hand” could allocate to vacancy creation [Mitchell calls this ‘the current savings of the capitalist-employers’, M.K.]. If that fundamental surplus constitutes a small fraction of a job’s output, it means that a given change in productivity translates into a much larger percentage change in the fundamental surplus [duhhh.., M.K.] . Because such large movements in the amount of resources that could potentially be used for vacancy creation cannot be offset by the invisible hand, significant variations in market tightness ensue [‘the patent impossibility of selling goods at a profit, or even at costs’, M.K.], causing large movements in unemployment [‘brings on a crisis’, M.K.].

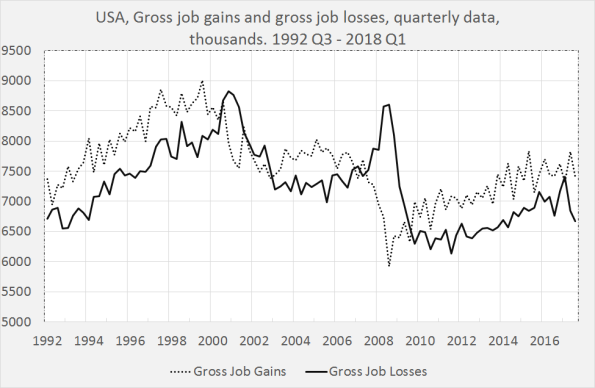

Graph 2.

The ‘Matching functions’ mentioined in the quote explain unemployment by assuming that finding a job or a worker takes time. And this does explain unemployment – part of it (2%-point?). The rest must be explained by crises and the inability of the market system to create jobs. As is clear from comparing graph 2, short-lived crises cause lower levels of job creation and higher levels of job destruction. Basically, these swings are not even that large. But together they lead to a fast increase in unemployment which take years to overcome. Sargent and Ljundqvist did re-invent the wheel. If they had red Rodbertus, Sismondi, Marx, Owen or Mitchell they would have known.

Fun fact: the neoclassical ‘DSGE’ model of Bokan e.a. distinguishes a class of bankers, a class of entrepreneurs (let’s call them ‘capitalists’, as they own all the capital) and a class of households which have nothing else to sell than their labour… The model knows a ‘positive wage mark-up’ but change this into a ‘wage mark down’ (for instance caused by ‘monpsonie’ on the labor market, i.e. by strong labor market power of employers, and it’s starting to look pretty Marxist, too.

Amazing.