From David Ruccio Mainstream economists continue to insist that workers benefit from economic growth, because wages rise with productivity. Here’s the argument as explained by Donald J. Boudreaux and Liya Palagashvili: Firms cannot afford a misalignment of their workers’ pay and productivity increases—the employees will move to other firms eager to hire these now more productive workers. Higher economy-wide productivity, after all, means that workers add more to the bottom lines of employers throughout the economy. To secure the services of these more-productive workers, firms bid up worker pay. This competition for labor services is what links pay to productivity. Except, of course, the link between wages and productivity has been severed for decades now, going back to the

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Mainstream economists continue to insist that workers benefit from economic growth, because wages rise with productivity.

Here’s the argument as explained by Donald J. Boudreaux and Liya Palagashvili:

Firms cannot afford a misalignment of their workers’ pay and productivity increases—the employees will move to other firms eager to hire these now more productive workers. Higher economy-wide productivity, after all, means that workers add more to the bottom lines of employers throughout the economy. To secure the services of these more-productive workers, firms bid up worker pay. This competition for labor services is what links pay to productivity.

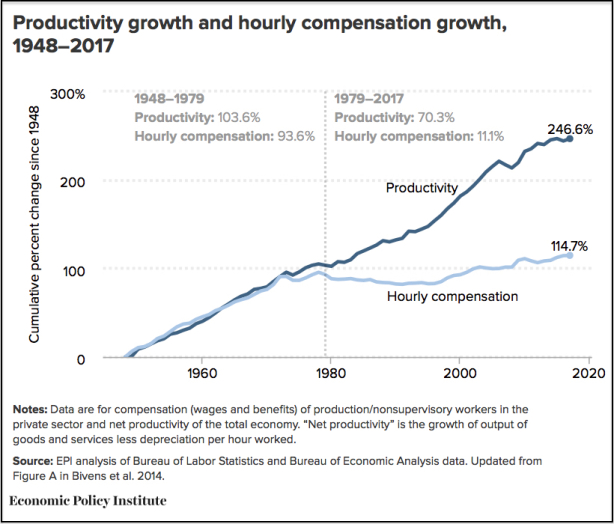

Except, of course, the link between wages and productivity has been severed for decades now, going back to the late-1970s. Since then, as the folks at the Economic Policy Institute have shown, productivity has increased by 70.3 percent but average worker’s wages have risen by only 11.1 percent.

So, no, there is no necessary or automatic link between productivity and wages within the U.S. economy. There may have been such a relationship after World War II, during the so-called Golden Age of American capitalism, but not in recent decades.*

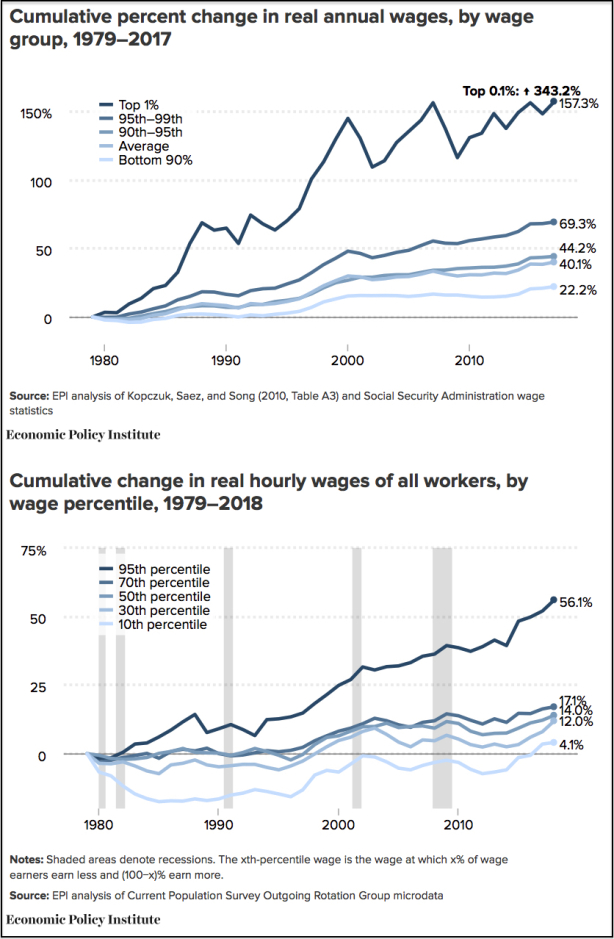

A natural question that arises is just where did the excess productivity—the extra surplus U.S. employers appropriated from their workers—go? A significant proportion, as I showed last year, went to higher corporate profits. Another large portion went to those at the very top of the wage distribution.

As is clear in the chart above, the top 1 percent of earners saw cumulative gains in annual wages of 157.3 percent between 1979 and 2017—far in excess of economy-wide productivity growth and nearly four times faster than average wage growth (40.1 percent). Over the same period, top 0.1 percent earnings grew 343.2 percent, with the latest spike reflecting the sharp increase in executive compensation.

In other words, corporate executives—on both Main Street and Wall Street—have been able to share in the extra booty captured from American workers, who were forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work for wages that have barely increased in recent decades.

That combination of stagnant wages for most workers and the ability of those at the top to capture a large portion of the extra surplus is therefore at the root of increasing inequality in the United States.

*Even then, as I explained back in 2017:

The fact is, the supposed Golden Age of American capitalism was based on a set of institutions that allowed the boards of directors of large corporations to appropriate a growing surplus and to distribute it as they wished. At first, during the immediate postwar period, that meant growing incomes for those in the bottom 90 percent. But, even then, the mechanisms for distributing income remained in the hands of a very small group at the top. And they had both the interest and the means to stop the growth of wages, get even more surplus (from U.S. workers and, increasingly, workers around the globe), and distribute a greater share of that surplus to a tiny group at the very top of the distribution of income.