Good news: given the results of the European elections it would seem that French and European citizens are becoming more concerned about global warming. The problem is that the election which has just taken place did little to further the basic issue. In real terms, which political forces do the ecologists intend to govern with and what is their programme for action? In France, the Greens achieved a respectable score gaining 13% of the votes. But, given that they had already obtained 11% in the 1989 European elections, 10% in 1999 and 16% in 2009, there is nothing to show that an autonomous majority of the Greens is within reach. In the European Parliament the Greens will have almost 10% of the seats (74 out of 751). This is better than in the outgoing parliament where their

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english, Non classé

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

Good news: given the results of the European elections it would seem that French and European citizens are becoming more concerned about global warming. The problem is that the election which has just taken place did little to further the basic issue. In real terms, which political forces do the ecologists intend to govern with and what is their programme for action? In France, the Greens achieved a respectable score gaining 13% of the votes. But, given that they had already obtained 11% in the 1989 European elections, 10% in 1999 and 16% in 2009, there is nothing to show that an autonomous majority of the Greens is within reach. In the European Parliament the Greens will have almost 10% of the seats (74 out of 751). This is better than in the outgoing parliament where their share was only 7% (51 seats) but this does force us to ask the question concerning alliances. Now the decision-makers in the Greens, intoxicated by their success, particularly in France, refuse to say whether they would like to govern with the left or with the right.

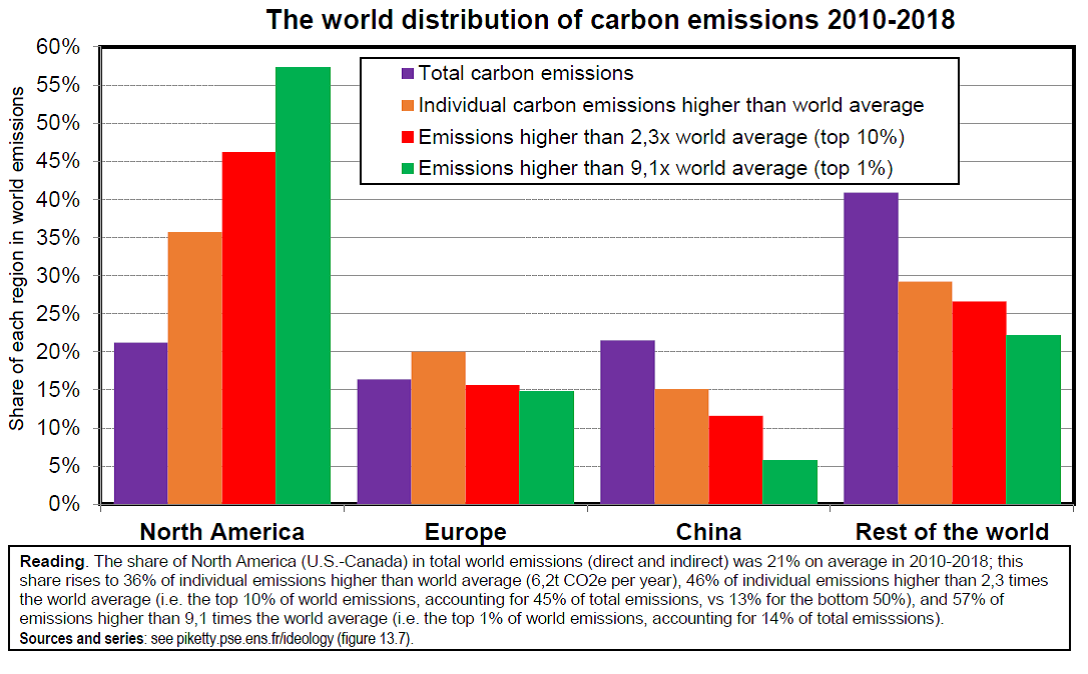

However, it is increasingly clear that the resolution of the climate challenge will not be possible without a strong movement in the direction of the compression of social inequalities at all levels. With the present magnitude of inequality, the advance towards austerity of energy will be wishful thinking. In the first instance because carbon emissions are strongly concentrated amongst the rich. At world level, the richest 10% are responsible for almost half the emissions and the top 1% alone emit more carbon than the poorest half of the planet. A drastic reduction in purchasing power of the richest would therefore in itself have a substantial impact on the reduction of emissions at global level.

Furthermore, it is difficult to see how the middle and working classes in the rich countries as in the emerging economies would accept to change their lifestyle (which is nevertheless essential) if they do not have the proof that the richest are also involved. The chain of political events observed in France in 2017-2019, which was strangely absent from the campaign, provides a dramatic and symbolical illustration of this need fot justice. The principal of the carbon tax was relatively well accepted in France in 2017 and it was intended to increase it regularly until 2030 to enable the country to reduce its emissions in keeping with pledges made under the Paris Accords.

But if a progression of this sort is to be acceptable, it is essential that it affect the biggest polluters at least as much as those with more modest incomes and that the totality of the product of the tax be allocated to the energy transition and used to assist the households most affected. The Macron government has done just the opposite. The taxes on fuels paid by the lowest incomes have been used to finance other priorities, beginning with the abolition of the wealth tax (ISF) and the progressive tax on incomes from capital. As the IPP (Institut des Politiques Publiques) has shown, between 2017 and 2019, the result has been an increase in 6% of the purchasing power of the top 1% and of 20% of the top 0.1% of the richest.

Given the social unrest, the government could have decided to cancel its gifts to the richest and to devote the money at long last to the climate and to compensating the poorest. On the contrary: as stubborn as Sarkozy between 2007 and 2012, with his pro-rich tax shield, Macron has decided to stick with his gifts to the rich and to cancel the increases in the carbon tax in complete disregard for the Paris Accords – today nobody knows when the carbon tax will be reinstated. By choosing to make the abolition of the wealth tax (ISF) the symbol of his policy, the party of the President has confirmed that he is indeed the heir to the liberal and pro-business right wing. The sociological structure of his electorate, focused on top incomes and wealth, in 2017 and even more so in 2019, means there can be no doubt about this.

In these conditions, one might wonder why the French or German Greens envisage governing with the liberals and the conservatives. The desire to access responsibilities is only human. But can we be sure that this is really in the interest of the planet? If the left-wing and the ecologists were to have allied in France, they would have overtaken the liberals and the nationalists. If they were to unite in the European Parliament they would form by far the biggest group and could have more influence. If a social-federal and ecological alliance of this sort were to come into existence, the various left-wing would also have to go some of the way. Les Insoumis in France and Die Linke in Germany cannot just say that they want to change the present version of Europe or to get out of the treaties. They have to explain which new treaties they would like to sign. As far as the socialists and social-democrats are concerned, their practice of power does mean that they bear considerable responsibility for the breakdown of the political system and they have a central role to play to enable its reconstruction. They will have to recognise past errors: they are largely responsible for forging the present European framework, in particular by organising the free circulation of capital without taxation, or by leading us to believe that they were going to renegotiate the treaties whereas, in reality, they have no precise plan.

It is possible to build a model for equitable and sustainable development in Europe, but this demands discussion and difficult choices: all the more reason to get down to work with no more ado.