Before the 2007-2008 crisis the balance sheet of the European Central Bank (that is, the totality of securities owned and loans granted by the ECB) was approximately 1000 billion Euros, or barely 10% of the GDP of the Euro zone. In 2019 it had risen to 4700 billion Euros, or 40% of the GDP of the zone. Thus between 2008 and 2018, the ECB has implemented a monetary creation equivalent to over one and a half years of the French GDP, one year of German GDP, or 30% of the GDP of the Euro zone (or 3% of GDP in additional monetary creation each year for 10 years). These considerable resources are for example three times higher than the total budget of the European Union during the same period (1% of GDP per annum, all categories of expenditure taken together, from agriculture to Erasmus to

Topics:

Thomas Piketty considers the following as important: in-english

This could be interesting, too:

Thomas Piketty writes Regaining confidence in Europe

Thomas Piketty writes Trump, national-capitalism at bay

Thomas Piketty writes Democracy vs oligarchy, the fight of the century

Thomas Piketty writes For a new left-right cleavage

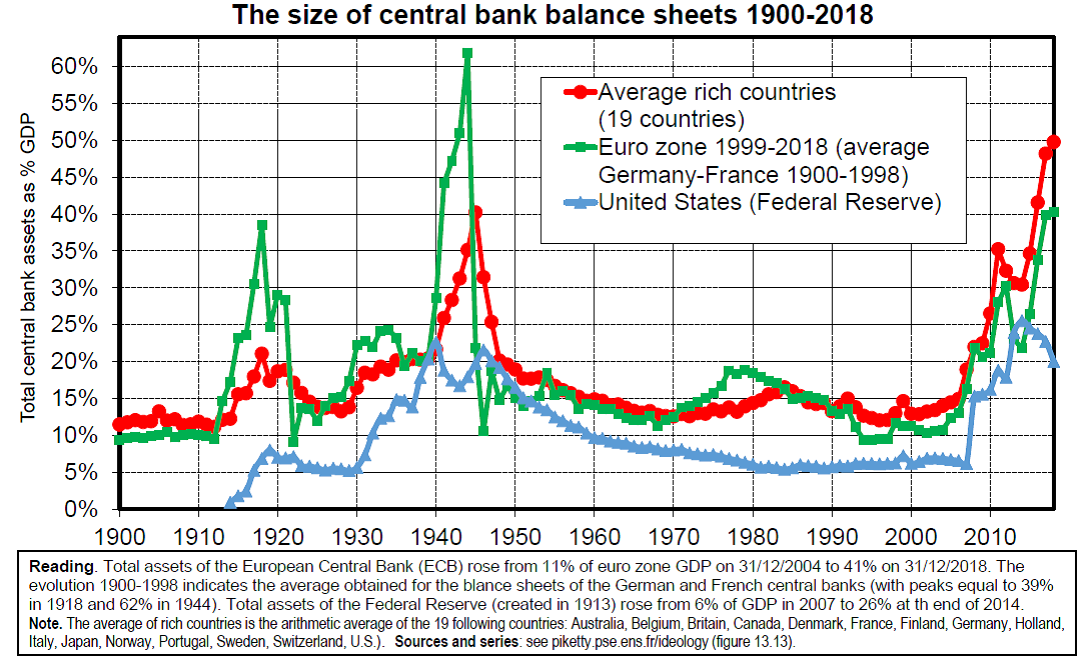

Before the 2007-2008 crisis the balance sheet of the European Central Bank (that is, the totality of securities owned and loans granted by the ECB) was approximately 1000 billion Euros, or barely 10% of the GDP of the Euro zone. In 2019 it had risen to 4700 billion Euros, or 40% of the GDP of the zone. Thus between 2008 and 2018, the ECB has implemented a monetary creation equivalent to over one and a half years of the French GDP, one year of German GDP, or 30% of the GDP of the Euro zone (or 3% of GDP in additional monetary creation each year for 10 years). These considerable resources are for example three times higher than the total budget of the European Union during the same period (1% of GDP per annum, all categories of expenditure taken together, from agriculture to Erasmus to the regional funds and research). These resources have enabled the ECB to intervene massively on the financial markets, to buy public and private debt securities and to make loans to the banking sector to guarantee solvency.

These policies have probably prevented the “great recession” in 2008 from becoming the “great depression” as was the case between 1929 and 1935. At the time, the central banks were shaped by a liberal orthodoxy based on non-intervention and had allowed a wave of bank failures to take place. This precipitated the collapse of the economy, the explosion of unemployment, the rise of Nazism and the march towards war. The fact that on this point at least history has taught us a lesson and that in 2008 (almost) nobody suggested a repetition of this « liquidationist » experience is obviously a good thing. Confronted with the extreme weaknesses of global financial capitalism, the central banks were in fact the only public institutions capable of avoiding a cascade of bank failures in the emergency.

The problem is that not all problems can be settled by monetary creation and the boards of directors of central banks and that these episodes have profoundly and permanently disrupted the collective representations in this respect. Before 2008, the prevailing opinion was that it was forbidden (or at least highly unadvisable) to carry out a monetary creation of such magnitude. This conception had been imposed in the 1980s following the “stagflation” of the 1970s (a mix of slow growth and high inflation). This was the climate in which the Maastricht Treaty (1992) which was to give birth to the Euro in 1999-2002 was conceived. The huge monetary creation which has taken place since 2008 has shattered this consensus. Following the creation in the click of a mouse, by the ECB of 30% of the GDP to save the banks, in Europe today, many voices clamour (for example with the project of the finance-climate pact) for a repetition of the same thing to finance the energy transition, to reduce inequalities or invest in research and training. Similar demands are also being expressed in the United States and in other regions of the world. They are natural and legitimate and it will not be possible to simply dismiss them.

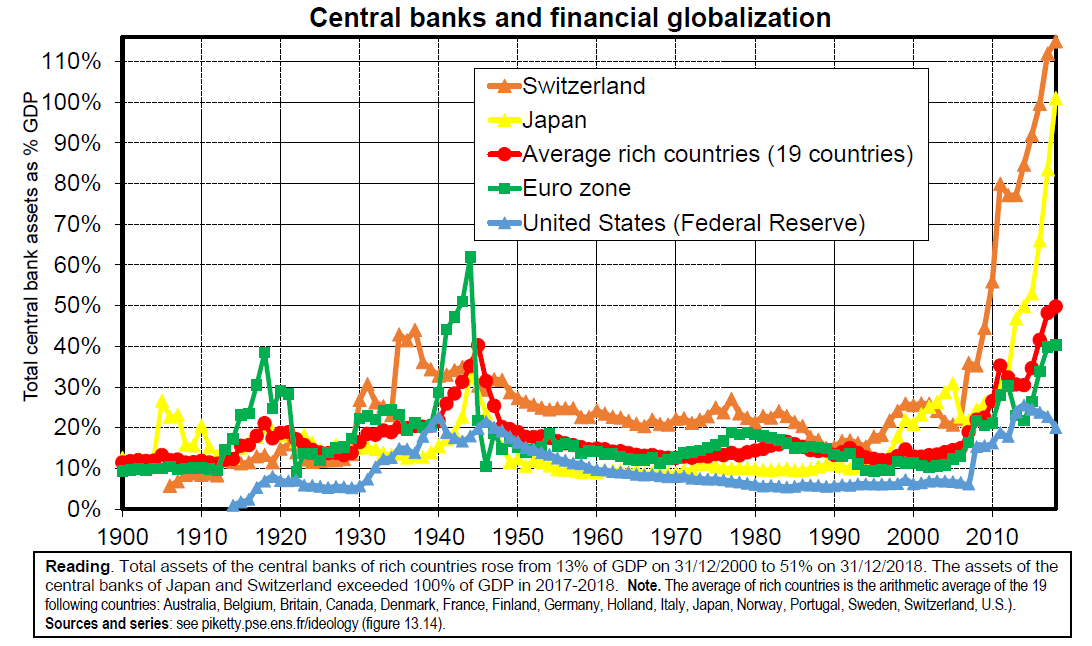

Several points must however be clarified. It is very possible that the central banks may again increase the size of their balance sheets (these have already risen to 100% of GDP in Japan and in Switzerland) in order to deal with financial crises to come, or simply to follow the evolution of the balance sheets in the private sector (over 1000% of GDP at present, as compared with 300% in the 1970s). There is nothing in the slightest reassuring about this rational of a never-ending high-speed chase: it would be better to set up the regulations required to end this hyper-financialisation and to reduce private balance sheets.

Furthermore, in a context of sluggish growth, of near-zero interest rates and non-existent inflation, it is legitimate for the public authorities to take on more debt to invest in the climate and in training, with the support of central banks. It is particularly paradoxical to observe that the total public expenditure in education (primary, secondary and higher) has been stagnating in the richer countries at around 5% of GDP since the 1980s, whereas the proportion of an age group entering higher education has risen from less than 20% to over 50%. In the European context this will however demand an in-depth intellectual and political reform. The questions of investment, debt and of money must be discussed openly in the context of a parliamentary body in place of the automatic budgetary rules (constantly circumvented) and the usual closed doors. These discussions involve the whole of society and cannot be left to councils of ministers of finance or governors of central banks.

Finally, and above all, the monetary expansion which took place in the period 2008-2018 must not lead to a new form of monetarist illusion. The considerable challenges which are ours (global warming, the rise of inequalities) do not simply demand that we mobilise adequate resources. They also demand that we build new norms of justice in the distribution of effort, which involves the adoption by elected assemblies of progressive taxes on income, financial assets and carbon emissions and by the implementation of a new system of financial transparency. The creation of money can help, provided that it is not a fetish and remains in its proper place: namely a tool within a collective system in which taxes and parliaments must retain the main role.