On June 17 Olivier Blanchard, an influential economist, held a dinner speech at the ECB Sintra Forum. Weird. Nothing changed. No Hyman Minsky. No Claudio Borio. No Ulrich Bindseil and intertemporal instability of the asset side of bank balance sheets. No Flow of Funds. Nothing of the kind. His solution for the problems of the Eurozone: get relative prices right and, trust me, general neoclassical equilibrium will return. Just plain old 2007 macro-economics. The whole reason we’re stuck in the mud is according to him that the – unobservable – ‘natural rate of interest’ has declined and has to increase again. Just get prices right (read: lower wages and the interest rate), which is more difficult when the natural rate of interest and inflation is low, and wait. In the meantime, as

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

On June 17 Olivier Blanchard, an influential economist, held a dinner speech at the ECB Sintra Forum. Weird. Nothing changed. No Hyman Minsky. No Claudio Borio. No Ulrich Bindseil and intertemporal instability of the asset side of bank balance sheets. No Flow of Funds. Nothing of the kind. His solution for the problems of the Eurozone: get relative prices right and, trust me, general neoclassical equilibrium will return. Just plain old 2007 macro-economics. The whole reason we’re stuck in the mud is according to him that the – unobservable – ‘natural rate of interest’ has declined and has to increase again. Just get prices right (read: lower wages and the interest rate), which is more difficult when the natural rate of interest and inflation is low, and wait. In the meantime, as interest rates are lower government expenditure might be a little higher to ease the transition period and to boost investments. What does this man still miss, after all these years, monetary and otherwise?

First, Blanchard ridicules the ‘Two Pillar’ strategy of the ECB. The two pillar strategy consists of:

- not just looking at ‘real’ macro data like ‘real’GDP and current accounts

- but also at monetary developments in a Flow of Funds framework.

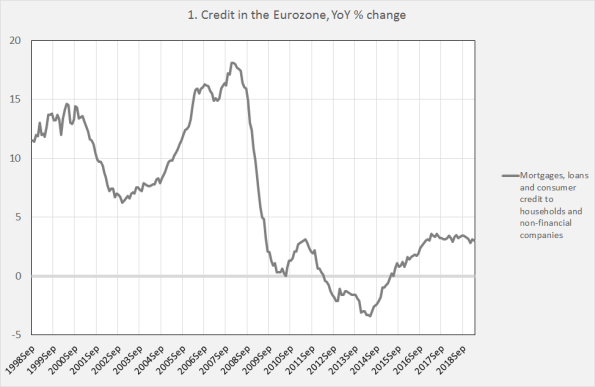

The monthly monetary press release of the ECB, which is part of its second pillar, consists of an analysis of money growth based on a Flow of Funds framework showing the changes in different kinds of credit and different kinds of counterparts, like households and non-financial companies. It teaches us that, in May, credit provided by banks to non-financial companies increased with 3,6% compared with one year before. Graph 1 is based upon these data which are also available on the national level and show, among other things, the unsustainable development of ‘credit’ in countries like Ireland, Spain, the Baltic states. Not entirely coincidentally, the 2008 crisis struck these countries already in 2007, judging by the pre-crisis employment peak. The ECB could have known. If only they had taken their own second pillar more serious! Alas, at the time they listened to much to economists like Olivier Blanchard, an influential economist who however still does not seem to grasp the idea of financial cycles as put forward by Claudio borio of the Bank of International Settlements. Credit has to keep flowing. But not, as before 2008, to prop up asset prices including house prices. And there can be too much of a good thing. Flow of Funds analysis should be the center of every macro-economic education and it’s painful to see somebody who is considered to be a fine macro-economist dismissing it. Blanchard did not look and still does not look at money and the monetary economy. That’s what he misses.

Second. Blanchard points at relative prices (read: lower wages) as a recipe to cure output gaps (read: persistent high unemployment). If prices are right – especially the price of labor and the interest rate set by that peculiar branch of the government called the Central Bank – eventually all will be well. Eventually. But it won’t. Not even in Greece where the European Commission forced the country to lower nominal wages with around 40% (and why should it when demand was constrained in the rest of the EU!). But it did constrain domestic demand, leaving Greece with a permaslump Europe hadn’t seen in generations. Well, that’s not entirely true. It left Greece in the same position as the Western Balkan countries which also found themselves in a permaslump. Beggar yourself as well as your neighbor policies didn’t work. Blanchard seems to have missed developments in Greece. Lower wages did not work.

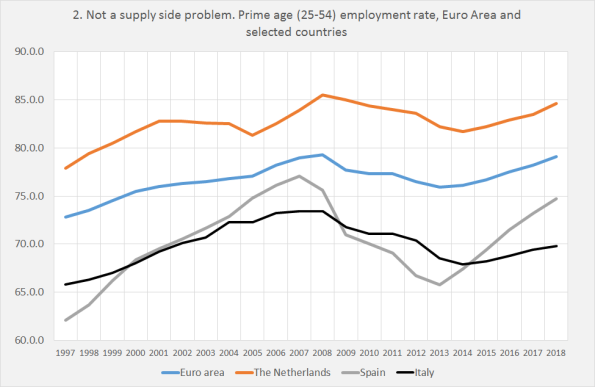

Third: Blanchard seems to be unaware of the present discussion about (un)employment and the output gap. He states that there is a discussion if the Eurozone is in a situation of an output gap (what kind of bubble is this man living in?) but he also states that, looking at inflation, there is at least in some countries a clear output gap. But should we look at inflation? For anybody following this discussion it’s clear that we’ve gotten (un)employment quite wrong during the last decades. Four percent headline unemployment is not low and indicates considerable slack in the economy; governments and central banks should aim at 3% or even lower. Also, the weird neoclassical idea, inherent in the models of neoclassical macro models of Blanchard, that lower wages will lead to less labor supply (and hence lower unemployment) were clearly wrong (Greece!). This should have been the focus of his speech. Lowering wages does not work to limit the supply of labor! But even aside of this there still is a load of slack. To show this I will look at another indicator of labor market performance now in vogue: prime age employment (graph 2), even when the most dynamic employment developments post 2008 are in the 54+ age category. On the Eurozone level, prime age employment is still low and even in countries with a high level like the Netherlands it still is below pre-crisis levels (might have changed since the end of 2018). The situation in Spain and Italy is dismal – in a sense, these countries have not been able to keep up with the rapdily rising activity rate of women. It is of course a complicated question how all these people have to be employed. Or, complicated? We do need this Green Deal. Badly. Construction workers in Spain were laid off and not paid to put solar cells above parking spaces, on top of buildings and other unused areas or to insulate buildings. What a waste. Blanchard should have looked at people, not at inflation.

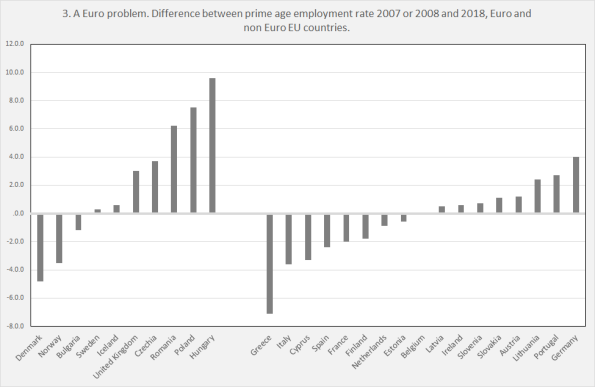

A question is of course: how much of this development is due to the Euro and Eurozone policies? This question is difficult to answer. Graph 3 shows the difference between 2007 or 2008 employment rate and the latest data. Compare Greece with Hungary. Compare Italy with Poland.

There are some remarkable countries. The deterioration of the prime age employment rate in Denmark is worse than in Italy and Spain! Even then, developments in the Eurozone are dismal. In 2018, eleven (11!) years after the crisis started, prime age employment is still low in many countries. We do not need low interest rates. We need credit, to finance new investments. Low rates don’t work. Low wages don’t work. Investments do. We do need this New Green Deal. We do have the people. Let’s start. And forget about inflation. We’re still in a slump. That’s what Blanchard is missing.