From David Ruccio Obscene levels of economics inequality in the United States are now so obvious they’ve become one of the main topics of public and political discourse (alongside and intertwined with two others, the climate crisis and the impeachment of Donald Trump).* Most Americans, it seems, are aware of and increasingly incensed by the grotesque and still-growing gap between a tiny group at the top—wealthy individuals and large corporations—and everyone else. And this sense of unfairness and injustice is reflected in both the media and political campaigns. For example, Capital & Main, an award-winning nonprofit publication that reports from California, has launched a twelve-month long series on economic inequality in America, “United States of Inequality: 2020 and the Great

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Obscene levels of economics inequality in the United States are now so obvious they’ve become one of the main topics of public and political discourse (alongside and intertwined with two others, the climate crisis and the impeachment of Donald Trump).*

Most Americans, it seems, are aware of and increasingly incensed by the grotesque and still-growing gap between a tiny group at the top—wealthy individuals and large corporations—and everyone else. And this sense of unfairness and injustice is reflected in both the media and political campaigns. For example, Capital & Main, an award-winning nonprofit publication that reports from California, has launched a twelve-month long series on economic inequality in America, “United States of Inequality: 2020 and the Great Divide,” leading up to next year’s presidential election. And two of the leading presidential candidates in the Democratic Party, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, have responded by making economic inequality one of the signature issues of their primary campaigns, regularly describing the devastating consequences of the enormous gap between the haves and have-nots and proposing policies (such as a wealth tax) to begin to close the gap and mitigate at least some of its effects.**

As if on cue, we’re also seeing a pushback. It should come as no surprise that America’s billionaires—from Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz to multi-billionaire hedge-fund manager Leon Cooperman—have gone on the offensive, complaining about how the various tax proposals, if enacted, would reduce what they consider to be the fortunes they’ve earned and undermine two areas they alone control: private philanthropy and corporate innovation.*** And ironically, as Paul Waldman has claimed,

the more billionaires keep talking about how their taxes shouldn’t be raised, the more likely it is that their taxes will in fact be raised, one way or another.

Similarly predictable is the attempt to rejigger the numbers so that inequality in the United States appears to be much less than official sources report. For example, according to the Census Bureau [pdf], in 2018, the top quintile of households (with an average income of $233.9 thousand) had 17 times more than the bottom quintile (whose average income was only $13.8 thousand).**** Phil Gramm and John F. Early argue that “this picture is false” because it focuses only on money income and excludes both taxes and transfer payments.***** Their conclusion?

America already redistributes enough income to compress the income difference between the top and bottom quintiles. . .down to 3.8 to 1 in income received.

There is one kernel of truth in Gramm and Early’s analysis: while the rich pay more in taxes, government transfers make up a much larger share of income of those at the bottom.****** But their calculations dramatically overstate the extent to which taxes and transfers decrease the degree of economic inequality in the United States. That’s because they fail to include unreported capital income, including dividends and interest paid to tax-exempt pension accounts and corporate retained earnings (which are included in other data sets, such as G. Zucman, T. Piketty, and E. Saez, “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States” [http://gabriel-zucman.eu/usdina/]).

As is clear in the table above, in 2014 (the last year for which data are available), the system of taxes and transfers only reduces the degree of inequality (measured as the ratio of top 10 percent average incomes to bottom 50 percent average incomes) from 18.7 to 1 to 10.1 to 1. And if we focus on post-tax cash incomes (thus excluding non-cash transfers, essentially Medicaid and Medicare), the resulting correction is even less: to 11.8 to 1. In both cases, the decrease in inequality is much less than in the Gramm and Early calculations.

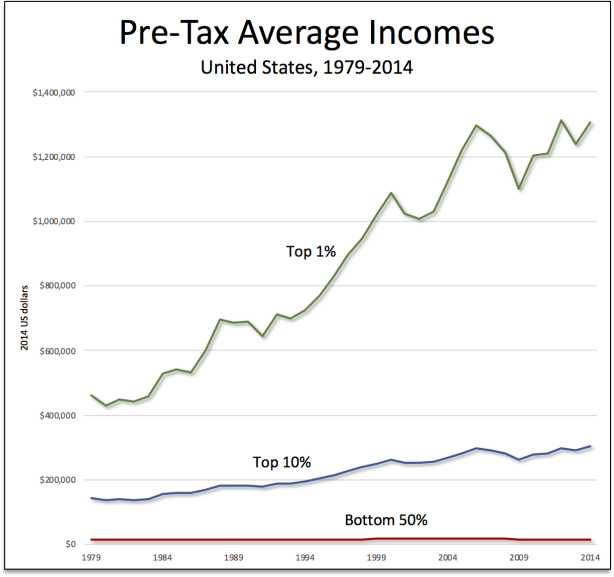

The fact is, there are severe limits on what taxes and transfers can achieve in the face of the massive changes in the pre-tax distribution of income that have occurred in the United States since 1979.

As readers can see in the table above, while the average pre-tax incomes of the bottom 50 percent of Americans stagnated from 1979 to 2014, those of the top 10 percent increased by 100 percent and the incomes of the top 1 percent soared by even more, 183 percent.

If we compare the real incomes of the same groups after taxes and transfers, it’s clear that while the incomes of the bottom 50 percent of Americans did in fact inch upward from 1979 to 2014 (by a total of 18 percent, or only 0.5 percent a year), progressive taxes and transfers did not hamper the upsurge of income at the top: the average post-tax incomes of the top 10 percent doubled (by 2.86 percent a year) and those of the top 1 percent grew by more than 160 percent (by 4.8 percent a year).*******

The small group at the top continues to pull away from everyone else, both before and after taxes and transfers.

In my view, the degree of economic inequality in the United States is so severe that it can’t be sidetracked by billionaire complaints or swept away by the calculations of conservative economists. And, for that matter, it can’t be solved by enacting more taxes on the ultra-rich and more transfer payments for the rest of Americans. The problem is simply too large and systemic.

Only by understanding and attacking the roots of the inequality that has characterized the U.S. economy for decades now will we be able to close the enormous gap that has undermined the American Dream and shredded the fabric of political and social life in the United States.

*But, contra New York University historian Timothy Naftali, this is not the first time “we are having a national political conversation about billionaires in American life.” In fact, I’d argue, it’s a recurring debate in American history, stretching back at least to the rise of populism in the late-nineteenth century (and perhaps earlier, for example, to Shays’ Rebellion) and including the strike wave after the Panic of 1873, the anti-trust movement of the early-twentieth century, the crash of 1929 and the First Great Depression, and most recently the attacks on finance and the Occupy Wall Street movement during the Second Great Depression. In all those cases, Americans engaged in an intense national discussion of inequality and the role of the economic elite in political and social life.

**Even centrist Democrats have taken up, if only timidly, the banner of the anti-inequality campaign. For example, Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-PA), who has endorsed Joe Biden for the Democratic nomination, told The Washington Post he is crafting a new wealth tax proposal to introduce in the House of Representatives. And Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA), who last month endorsed South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, has released a plan (with Sen. Chris Van Hollen of Maryland) for a new surtax on incomes over $2 million.

***The one area they don’t mention, which they also seek to control, is American politics—through lobbying, campaign donations, and the like. Wealthy individuals and large corporations attempt to exert such control although, as we just saw in Seattle—with Amazon’s $1.5 million campaign to unseat a socialist member of Seattle’s city council, Kshama Sawant—they’re not always successful.

****Money income includes the following categories: earnings; unemployment compensation; workers’ compensation; Social Security; supplemental security income; public assistance; veterans’ payments; survivor benefits; disability benefits; pension or retirement income; interest; dividends; rents, royalties, and estates and trusts; educational assistance; alimony; child support; financial assistance from outside of the household; and other income. The ratio of top to bottom rises to an astounding 60 to 1 in terms of only earnings.

*****The Wall Street Journal column doesn’t explain how the alternative calculations were conducted. But Early, in a Cato Institute report [pdf], does explain their methodology.

******According to my calculations from the most comprehensive source (from G. Zucman, T. Piketty, and E. Saez, “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States” [http://gabriel-zucman.eu/usdina/]), in 2014, the bottom 50 percent of Americans received 74 percent of their post-tax income from transfers while, for the top percent, it was 19.5 percent.

*******What of the billionaires? Between 1979 and 2014, the average real post-tax incomes of the top .001 percent grew by 387 percent (or 11.1 percent a year), almost as much as their pre-tax incomes.