From Lars Syll As yours truly has reported repeatedly during the last couple of years, university students all over Europe are increasingly beginning to question if the kind of economics they are taught — mainstream economics — really is of any value. Some have even started to question if economics is a science. At least two Nobel laureates in economics have tried to respond. This is Robert Shiller‘s answer: Critics of “economic sciences” sometimes refer to the development of a “pseudoscience” of economics, arguing that it uses the trappings of science, like dense mathematics, but only for show … My belief is that economics is somewhat more vulnerable than the physical sciences to models whose validity will never be clear, because the necessity for approximation is much stronger than

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Lars Syll

As yours truly has reported repeatedly during the last couple of years, university students all over Europe are increasingly beginning to question if the kind of economics they are taught — mainstream economics — really is of any value. Some have even started to question if economics is a science.

As yours truly has reported repeatedly during the last couple of years, university students all over Europe are increasingly beginning to question if the kind of economics they are taught — mainstream economics — really is of any value. Some have even started to question if economics is a science.

At least two Nobel laureates in economics have tried to respond.

This is Robert Shiller‘s answer:

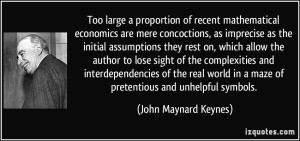

Critics of “economic sciences” sometimes refer to the development of a “pseudoscience” of economics, arguing that it uses the trappings of science, like dense mathematics, but only for show …

My belief is that economics is somewhat more vulnerable than the physical sciences to models whose validity will never be clear, because the necessity for approximation is much stronger than in the physical sciences, especially given that the models describe people rather than magnetic resonances or fundamental particles. People can just change their minds and behave completely differently. They even have neuroses and identity problems, complex phenomena that the field of behavioral economics is finding relevant to understanding economic outcomes.

But all the mathematics in economics is not charlatanism … While economics presents its own methodological problems, the basic challenges facing researchers are not fundamentally different from those faced by researchers in other fields. As economics develops, it will broaden its repertory of methods and sources of evidence, the science will become stronger, and the charlatans will be exposed.

And this is what Paul Krugman says on the question:

While economists using textbook macro models got things mostly and impressively right, many famous economists refused to use those models — in fact, they made it clear in discussion that they didn’t understand points that had been worked out generations ago. Moreover, it’s hard to find any economists who changed their minds when their predictions, say of sharply higher inflation, turned out wrong …

The problem lies not in the inherent unsuitability of economics for scientific thinking as in the sociology of the economics profession — a profession that somehow, at least in macro, has ceased rewarding research that produces successful predictions and rewards research that fits preconceptions and uses hard math instead.

My own take on the issue is that economics — and especially mainstream economics — has lost immensely in terms of status and prestige during the last years. Not the least because of its manifest inability to foresee the latest financial and economic crises — and its lack of constructive and sustainable policies to take us out of the crises.

We all know that many activities, relations, processes and events are uncertain and that the data do not unequivocally single out one decision as the only “rational” one. Neither the economist nor the deciding individual can fully pre-specify how people will decide when facing uncertainties and ambiguities that are ontological facts of the way the world works.

We all know that many activities, relations, processes and events are uncertain and that the data do not unequivocally single out one decision as the only “rational” one. Neither the economist nor the deciding individual can fully pre-specify how people will decide when facing uncertainties and ambiguities that are ontological facts of the way the world works.

Mainstream economists, however, have wanted to use their hammer, and so decided to pretend that the world looks like a nail. Pretending that uncertainty can be reduced to risk and construct models on that assumption have only contributed to financial crises and economic havoc.

How do we put an end to this intellectual cataclysm? How do we re-establish credence and trust in economics as a science? Five changes are absolutely decisive.

(1) Stop pretending that we have exact and rigorous answers on everything. Because we don’t. We build models and theories and tell people that we can calculate and foresee the future. But we do this based on mathematical and statistical assumptions that often have little or nothing to do with reality. By pretending that there is no really important difference between model and reality we lull people into thinking that we have things under control. We haven’t! This false feeling of security was one of the factors that contributed to the financial crisis of 2008.

(2) Stop the childish and exaggerated belief in mathematics giving answers to important economic questions. Mathematics gives exact answers to exact questions. But the relevant and interesting questions we face in the economic realm are rarely of that kind. Questions like “Is 2 + 2 = 4?” are never posed in real economies. Instead of a fundamentally misplaced reliance on abstract mathematical-deductive-axiomatic models having anything of substance to contribute to our knowledge of real economies, it would be far better if we pursued “thicker” models and relevant empirical studies and observations. Mathematics cannot establish the truth value of a fact. Never has. Never will.

(3) Stop pretending that there are laws in economics. There are no universal laws in economics. Economies are not like planetary systems or physics labs. The most we can aspire to in real economies is establishing possible tendencies with varying degrees of generalizability.

(4) Stop treating other social sciences as poor relations. Economics has long suffered from hubris. A more broad-minded and multifarious science would enrich today’s economics and make it more relevant and realistic.

(5) Stop building models and making forecasts of the future based on totally unreal micro-founded macro models with intertemporally optimizing robot-like representative actors equipped with rational expectations. This is pure nonsense. We have to build our models on assumptions that are not so blatantly in contradiction to reality. Assuming that people are green and come from Mars is not a good — not even as a “successive approximation” — modelling strategy.