From Erik Reinert and issue 92 of RWER In complete contradiction to the ruling practice of the Marshall Plan at the time, Paul Samuelson started building what was to become Cold War economic theory with two articles in The Economic Journal in 1948 and 1949. Communism advanced under the utopian slogan “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”. With his renewed interpretation of David Ricardo, Paul Samuelson produced a counter-utopia: under the standard assumptions of neo-classical economics free trade would produce a tendency towards factor-price equalization: the prices of labor and capital would tend to equalize across the planet. This became the noble lie of the neo-classical economics and of neoliberalism as the West faced the evils of communism. Today’s

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Erik Reinert and issue 92 of RWER

In complete contradiction to the ruling practice of the Marshall Plan at the time, Paul Samuelson started building what was to become Cold War economic theory with two articles in The Economic Journal in 1948 and 1949. Communism advanced under the utopian slogan “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”. With his renewed interpretation of David Ricardo, Paul Samuelson produced a counter-utopia: under the standard assumptions of neo-classical economics free trade would produce a tendency towards factor-price equalization: the prices of labor and capital would tend to equalize across the planet. This became the noble lie of the neo-classical economics and of neoliberalism as the West faced the evils of communism.

Today’s economists would naturally tend to believe that Cold War Economics – the theories that stood victorious after the 1989 Fall of the Berlin Wall – is part of a tradition that has ruled in economic science since David Ricardo’s 1817 book. However, recent n-gram technology has made it possible to illustrate how David Ricardo and his theory of “comparative advantage” were virtually neglected until the Cold War.

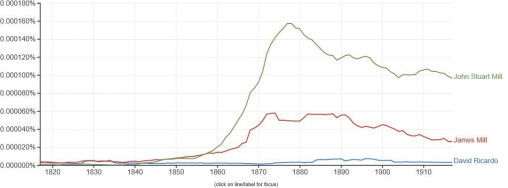

The n-grams below show how Cold War economics brought David Ricardo out of the shadows. Compared to other English economists and economic philosophers – father and son James and John Stuart Mill – David Ricardo had indeed been much less important during the first 100 years after his 1817 theory.

Figure 2 The frequency of “David Ricardo” (in English) during the first 100 years after the 1817 publication of his main work, Principles of Economics, compared to that of two other, then much more famous, English economists.

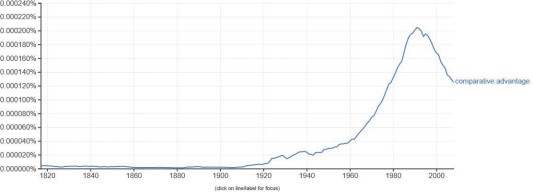

Figure 3 Frequency of the term “comparative advantage” (in English) from 1817 until today. As is clearly shown the term was very little used for the first 100 years of existence, but the use of the term started with the birth of the planned economy and exploded with the start of the Cold War in the late 1940s.

On the theoretical level, the Cold War (1947-1989) was fought between two cosmopolitical theories. Neither in neo-classical/neo-liberal theory nor in communism was the nation state a unit of analysis. In both theories the nation-state was not seen as having a place. Neo- classical economics is built on methodological individualism – the state assumed away – and also in Marxism the state was supposed to wither away as obsolete after a brief “dictatorship of the proletariat”. In practice, of course, it was not the state but the rights of individuals that withered away under communism.

An important goal of science must be objectivity. Friedrich Nietzsche described objectivity as attempting to gain as many perspectives as possible on a matter:

“There is only a perspective ‘seeing’, only a perspective ‘knowing’; and the more affects we allow to speak about one thing, the more eyes, different eyes, we can use to observe one thing, the more complete will our ‘concept’ of this thing, our ‘objectivity’, be.”9

In this way – by seeing the world from as many angles as possible – one can potentially understand the interplay between economic contexts and economic policies: how formulas for economic development will vary in different contexts. A condition for scientific objectivity, then, is the ability to observe diversity.

With Cold War neo-classical economics, however, came a theory a) void of context, and b) with only one angle from which to see international trade. With the politics of neoliberalism arriving with Thatcher and Reagan came two myths – not only of creating free trade as the historical normality, as did Samuelson – but as part and parcel of the same problem came the myth of laissez-faire. All seriously studying the subject have come up with the same conclusion as an American business historian did: “King Laissez Faire was not only dead; the hallowed report of his reign had all been a mistake”.10

As economics Nobel Laureate James Buchanan wrote: “Any generalized prediction in social science implies at its basis a theoretical model that embodies elements of an equality assumption. If individuals differ, one from the other, in all attributes, social science becomes impossible.”11 Faced with this trade-off between “science” and “diversity”, neo-classical economics chose a supposedly “scientific” path, by in effect making all human beings (perfect information) and all economic activities (perfect competition) qualitatively alike. The basic metaphor of economics became equilibrium, taken from the physics profession of the 1880s.

A great intellectual mystery of the 20th century is how, on the one hand, standardized mass production and the concomitant growing importance of increasing returns to scale under imperfect competition came to dominate economic life in the rich industrialized countries. On the other hand, sometime in the 1930s increasing returns to scale – the very basis for standardized mass production – was thrown out of economic theory because it was not compatible with equilibrium.12 The logical thing had been to throw out equilibrium because it was not compatible with the most prevalent of all economic “laws” at the time, increasing returns.

Some philosophers came to see diversity as a goal in itself. Johann Gottlob Fichte (1762- 1814) was one of them. When most Germans felt that the subdivision of Germany into a large number of small states – after the 1648 Peace of Westphalia there had been about 400 of them – Fichte argued that the diversity of the many states was an advantage.

The European Union has forced a one-size-fits-all policy on its member states, while at the same time locking many of them into the straightjacket of a common currency. “Fichte sought to establish that there were no inherent limits on the extent to which a world of multiple states would come to approximate his humanitarian ideal, despite remaining a world of states”.13 With an asymmetrical economic integration tearing the union apart, Fichte’s is a perspective which is probably worth re-considering in Europe, and also at the global level. read more

9 Nietzsche, Friedrich, Genealogy of Morals, third Essay, New York, Oxford University Press, 1999 [1887].

10 Lively, Robert, “The American System: A Review Article”, in Business History Review, Volume 29, Issue 1, March 1955, pp 81-96.

11 Buchanan, James, What Should Economists Do?, Indianapolis, Liberty Press, 1979, p. 231. Italics added.

12 For a discussion see Reinert, Erik, How Rich Countries Got Rich… and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor, London, Constable, 2007. New edition, New York, public affairs, 2019.