From David Ruccio Right now, the United States is mired in an economic depression, the Pandemic Depression, not dissimilar to what happened in the 1930s and again after the crash of 2007-08. Real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product contracted by an annual rate of 31.7 percent in the second quarter of 2020 (according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis) and at least 27 million American workers are currently unemployed (counting workers continuing to receive some kind of unemployment benefits, according to my own calculations).* By all accounts—from both macroeconomic data and anecdotes reported in the media—the current situation is an economic and social disaster equivalent to what the United States went through during the first and second Great Depressions. The question is, does

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Right now, the United States is mired in an economic depression, the Pandemic Depression, not dissimilar to what happened in the 1930s and again after the crash of 2007-08.

Real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product contracted by an annual rate of 31.7 percent in the second quarter of 2020 (according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis) and at least 27 million American workers are currently unemployed (counting workers continuing to receive some kind of unemployment benefits, according to my own calculations).* By all accounts—from both macroeconomic data and anecdotes reported in the media—the current situation is an economic and social disaster equivalent to what the United States went through during the first and second Great Depressions.

The question is, does mainstream macroeconomics have anything to offer in terms of insights about the causes of the current crises or what should be done to solve them?

Many readers are, I’m sure, skeptical, given the abysmal track record of mainstream macroeconomic thinking in the United States. Going back just a bit more than a decade, to the Second Great Depression, it’s clear that mainstream macroeconomists failed on all counts: they didn’t predict the crash; they didn’t even include the possibility of such a crash within their basic theory or models; and they certainly didn’t know what to do once the crash occurred.

Can they do any better with the current depression?

The example I want to use was recently posted by Harvard’s Greg Mankiw, the author of the best-selling macroeconomics textbook on the market. I know it’s not the most sophisticated (or, if you prefer, technical or detailed) discussion out there but it does matter: next year, thousands upon thousands of students will receive their basic training in mainstream macroeconomic theory and its application to the Pandemic Depression from Mankiw’s text.

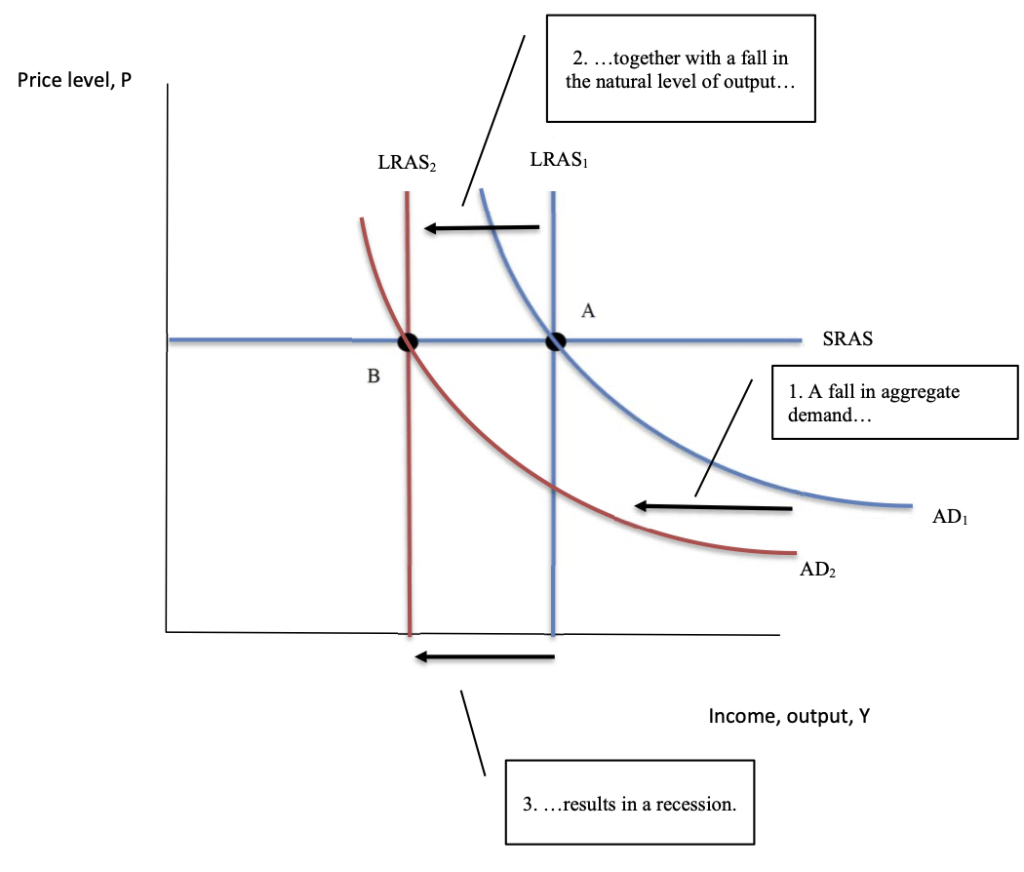

It should come as no surprise that Mankiw uses the macroeconomic model—of aggregate demand and supply—he has so laboriously built up over the course of many chapters to examine what he calls “the economic downturn of 2020.” His basic argument is that, first, aggregate demand declined (shifting to the left, from AD1 to AD2) due to a decline in the velocity of money (one of the exogenous variables that, in mainstream moderls, determines aggregate demand), and second, the long-run aggregate supply curve declines (shifts left, from LRAS1 to LRAS2), while the short-run aggregate supply curve (SRAS) stays the same. The result is a decline in output (the left-facing arrow at the bottom of the diagram).

This is all pretty straightforward stuff. Except: Mankiw wants to argue that it’s the “natural level of output” as represented by the long-run aggregate supply curve, not the perfectly elastic (or horizontal) short-run aggregate supply curve, that shifts to the left. Huh?

His only explanation is that

When a pandemic strikes and many businesses are temporarily closed, aggregate demand falls because people are staying at home rather than spending at those businesses. Because those businesses cannot produce goods and services, the economy’s potential output, as reflected in the LRAS curve, falls as well. The economy moves from point A to point B.

The problem is, there’s nothing in the way Mankiw has derived the long-run aggregate supply curve—from given resources (land, labor, and capital) and technology—that has changed. Instead, the shutdown of many businesses merely means that there’s enormous excess capacity in the economy. The “natural rate of output”—the level of output corresponding to the “natural level of unemployment”—remains as it was.

But Mankiw is trapped by his own model. The benefit of analyzing the current depression in terms of a shift in the long-run aggregate supply curve is that, as soon as the shutdown is lifted, the supply curve shifts back to the right and the economy moves back to its old long-run equilibrium. Problem solved!

And if the long-run aggregate supply curve doesn’t shift back to the right? Well, then, U.S. capitalism has in fact destroyed its resources—especially labor power—and the economy doesn’t recover, at least anytime soon.

Moreover, if he’d shifted the short-run aggregate supply curve (up in the diagram), well, then we’re in the land of inflation—with the price level rising—an even more severe decline in economic activity (smaller than B), and no return to long-run equilibrium. But prices are not, in general rising, which is why he uses the horizontal short-run aggregate supply curve in the first place (to reflect fixed prices, the result of monopoly enterprises).

Not only is Mankiw trapped by the logic of his own model. His analysis—both the model and the accompanying text—leaves out much of what is interesting and important about the Pandemic Depression.

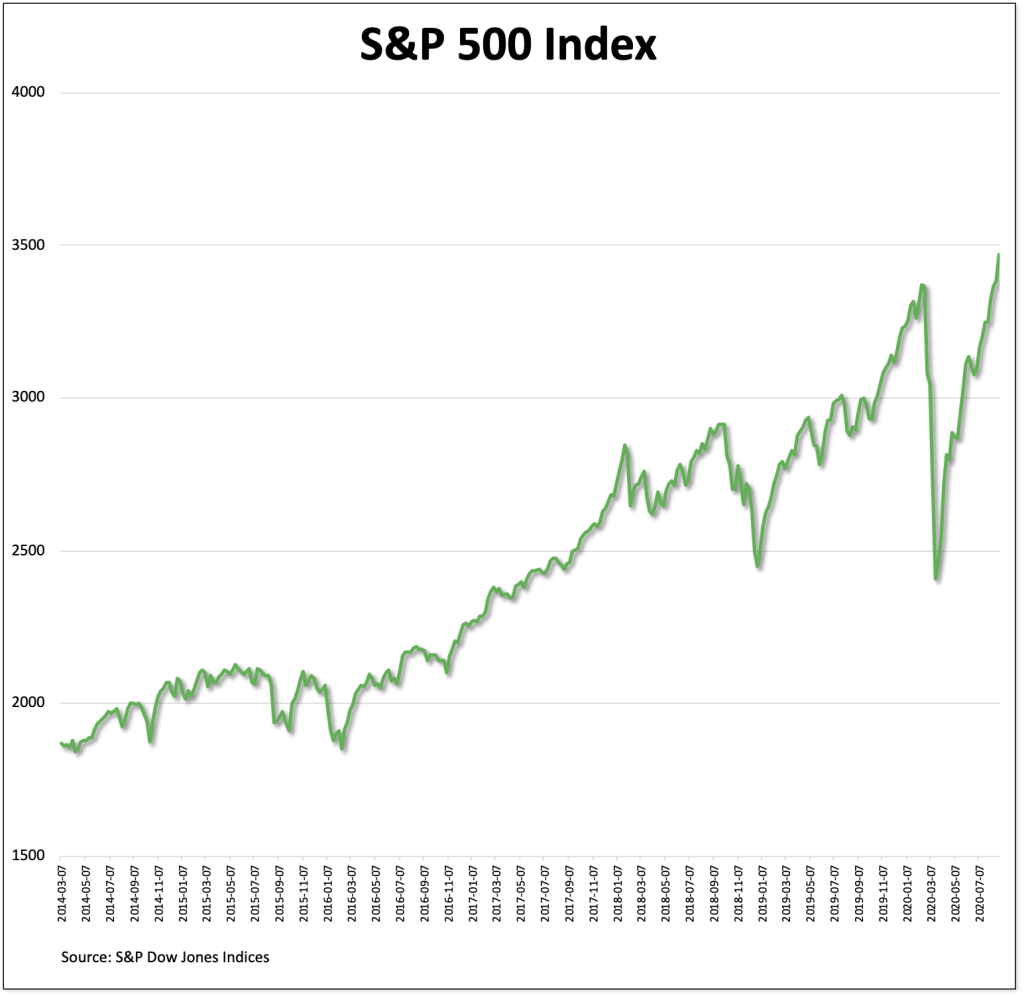

We’ve seen, for example, that U.S. stock markets, after an initial downturn, have soared to new record highs, even as national output declines and unemployment reached numbers of workers not seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s. That doesn’t even warrant a mention in Mankiw’s analysis—which involves a discussion of assistance to workers and small businesses but nothing about the trillions of dollars available to the Treasury and Federal Reserve to bailout large corporations, keep credit flowing, and boost equity markets.

But there’s an even larger problem in Mankiw’s basic model: all downturns, whether recession or depressions, are the result of “accidents.”

Some surprise event shifts aggregate supply or aggregate demand, reducing production and employment. Policymakers are eager to return the economy to normal levels of production and employment as quickly as possible.

And the Pandemic Depression? Well, according to Mankiw, it was “by design.” But the distinction is meaningless: in all cases, the downturn occurs because of something outside the model—by some kind of “shock.”

So, capitalism itself is absolved. In Mankiw’s model, and in mainstream macroeconomics more generally, there’s nothing in capitalism itself—how profit rates behave, what decisions capitalists make, the fragility of the financial sector, obscene levels of inequality, and so on—that causes the economy to collapse.

If we step outside the confines of Mankiw’s model, then we can begin to see how U.S. capitalism, while it did not create the novel coronavirus, certainly produced and exacerbated the destructive effects of the pandemic on the American economy. For example, after decades of neglect of the public healthcare system and attempts to shore up the private provision of healthcare in the United States, the country was ill-prepared to diagnosis and contain the pandemic. Even more, it worsened the already-grotesque inequalities of healthcare—as well as incomes, wealth, and household finances—it had originally created.

That same economic system also left in the hands of private employers—not the government or workers themselves—the decisions of whether to keep workers employed or, as happened across the country, to furlough or lay off tens of millions of their employees. Any to add to the misery: many of the workers who were supposed to be on temporary layoffs are now finding they’ve lost their jobs permanently and are spending more and more time attempting to find new jobs.

None of those pre-existing economic conditions figures in Mankiw’s analysis. They can’t, because they don’t exist within mainstream macroeconomics, which has been studiously constructed precisely to provide a hydraulic model of macroeconomic equilibrium—starting with full employment and price stability, one or another external “shock” that moves the economy away from there, and then automatic mechanisms to return the economy to its original position—on the basis of aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

And that’s how we get Mankiw’s excuse for the Pandemic Depression:

given the circumstances, a large economic downturn was arguably the best outcome that could be achieved.

———

*Millions more workers are either unemployed but not receiving benefits or involuntarily underemployed, working part-time (often with cuts in pay and benefits) when they prefer to be working full-time.