From Blair Fix Let’s talk econophysics. If you’re not familiar, ‘econophysics’ is an attempt to understand economic phenomena (like the distribution of income) using the tools of statistical mechanics. The field has been around for a few decades, but has received little attention from mainstream economists. I think this neglect is a shame. As someone trained in both the natural and social sciences, I welcome physicists foray into economics. That’s not because I think their approach is correct. In fact, I think it is fundamentally flawed. But it is only by engaging with flawed theories that we can learn to do better. What is important about econophysics, is that it demonstrates a flaw that runs throughout economics: the idea that we can explain macro-level phenomona from micro-level

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Blair Fix

Let’s talk econophysics. If you’re not familiar, ‘econophysics’ is an attempt to understand economic phenomena (like the distribution of income) using the tools of statistical mechanics. The field has been around for a few decades, but has received little attention from mainstream economists. I think this neglect is a shame.

As someone trained in both the natural and social sciences, I welcome physicists foray into economics. That’s not because I think their approach is correct. In fact, I think it is fundamentally flawed. But it is only by engaging with flawed theories that we can learn to do better.

What is important about econophysics, is that it demonstrates a flaw that runs throughout economics: the idea that we can explain macro-level phenomona from micro-level principles. The problem is that in all but the simplest cases, this principle does not work. Yes, complex systems may be reduced to simpler pieces. But rarely can we start with these simple pieces and rebuild the system. That’s because, as physicist Philip Anderson puts it, ‘more is different‘.

What follows is a wide-ranging discussion of the triumphs and pitfalls of reduction and resynthesis. The topic is econophysics. But the lesson is far broader: breaking a system into atoms is far easier than taking atoms and rebuilding the system.

Let there be atoms!

To most people, the idea that ‘matter is made of atoms’ is rather banal. It ranks with statements like ‘the Earth is round’ in terms of near total acceptance.1 Still, we should remember that atomic theory is an astonishing piece of knowledge. Here is physicist Richard Feynman reflecting on this fact:

If, in some cataclysm, all of scientific knowledge were to be destroyed, and only one sentence passed on to the next generations of creatures, what statement would contain the most information in the fewest words? I believe it is atomic hypothesis that … all things are made of atoms.

(Richard Feynman, Lectures on Physics)

Feynman spoke these words in the 1960s, confident that atoms existed. Yet if he’d said the same words a century earlier, they would have been mired in controversy. That’s because in the 19th century, many scientists remained skeptical of the atomic hypothesis. And for good reason. If atoms existed, critics observed, they were so small that they were unobservable (directly). But why should we believe in something we cannot see?

Today, of course, we can see atoms (using scanning transmission electron microscopes). But long before we achieved this feat, most scientists accepted the atomic hypothesis. Why? Because multiple lines of evidence pointed to atoms’ existence. Here’s how Richard Feynman put it:

How do we know that there are atoms? By one of the tricks mentioned earlier: we make the hypothesis that there are atoms, and one after the other results come out the way we predict, as they ought to if things are made of atoms.

(Richard Feynman, Lectures on Physics)

One of the first hints that atoms existed came from chemistry. When combining different elements, chemist John Dalton discovered that the masses of the reactants and product always came in whole-number ratios. This ‘law of multiple proportions’ suggested that matter came in discrete bits.

Another line of evidence for atomic theory came from what is today called ‘statistical mechanics’. This was the idea that macro properties of matter (such as temperature and pressure) arose from the interaction of many tiny particles. The key inductive leap was to assume that these particles obeyed Newton’s laws of motion. At the time, this assumption was a wild speculation. And yet it turned out to be wildly successful.

A gas of billiard balls

By the mid-19th century, the properties of gases had been formulated into the ‘ideal gas law’. This was an equation that described how properties like pressure, volume and temperature were related. But what explained this law?

Enter the kinetic theory of gases. Suppose that a gas is composed of tiny particles that collide like billiard balls. Next, assume that these collisions obey Newton’s laws. Last, assume that collisions are elastic (meaning kinetic energy is conserved). What does this imply?

It turns out that these assumptions imply the ideal gas law. So here we have the reasoning that Richard Feynman described: we hypothesize that there are atoms, and then the “results come out the way we predict, as they ought to if things are made of atoms.” What was exciting about this particle model was that it gave a micro-level definition of temperature and pressure. Temperature was the average kinetic energy of gas particles. And pressure was the force per area imparted by particles as they collided with the container.

As the mathematics of this kinetic model were developed further, there came another surprise. From equality came inequality. The ‘equality’ here refers to the underlying process. In the kinetic model, each gas particle has the same chance of gaining or losing energy during a collision. One might think, then, that the result should be uniformity. Each particle should have roughly the same kinetic energy. The mathematics, however, show that this is not what happens.

Instead, when James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann fleshed out the math of the kinetic model, they found that from equality arose inequality. Due only to random collisions, gas particles should have a wide distribution of speed.

Figure 1 illustrates this counter-intuitive result. The top frame shows a simple model of a gas — an ensemble of billiard balls colliding in a two dimensional container. The collisions are uniform, in the sense that each particle has the same chance of gaining/losing speed. And yet the result, shown in the bottom frame, is an unequal distribution of speed.

The blue histogram (in Figure 1) shows the distribution of speeds found in the modeled gas particles. Because there are relatively few particles (a few hundred), their speed distribution jumps around with time. But if we were to add (many) more particles, we expect that the speed distribution would converge to the yellow curve — the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

This particle model demonstrates how a seemingly equal process (the random exchange of energy) can give rise to wide inequalities. If econophycisists are correct, this model tells us why human societies are mired by inequality. It’s just basic thermodynamics.

Energized particles, monetized humans

After Maxwell and Boltzmann, statistical mechanics gave rise to a long string of successes that bolstered the atomic hypothesis. The icing on the cake came in 1905, when Albert Einstein used the kinetic model to explain Brownian motion (the random walk taken by small objects suspended in a liquid). It’s hard not to be impressed by this success story.

Now let’s fast forward to the late 20th century. By then, statistical mechanics was a mature field and the low-hanging fruit had long since been picked. And so physicists widened their attention, looking for other areas where their theories might be applied.2

Enter econophysics. In the 1990s, a small group of physicists set their sites on the human economy. Perhaps, they thought, the principles of statistical mechanics might explain how humans distribute money?3

Their idea required a leap of faith: treat humans like gas particles. Now, humans are obviously more complex than gas molecules. Still, econophysicists highlighted an interesting parallel. When humans exchange money, it is similar to when gas particles exchange energy. One party leaves with more money/energy, the other party leaves with less. Actually, the parallel between energy and money is so strong that physicist Eric Chaisson describes energy as the “the most universal currency known in the natural sciences” (emphasis added).

With the parallel between energy and money, ecophysicists arrived at a startling conclusion. Their models showed that when humans exchange money, inequality is inevitable.

Objection!

When econophysicists began publishing their ‘kinetic-exchange models’ of income and wealth, social scientists greeted them with skepticism. People, social scientists observed, are not particles. So it is inappropriate to use the physics of inanimate particles to describe the behavior of (animate) humans.

In the end, I think this criticism is warranted … but for reasons that are probably different than you might expect. Before I get to my own critique, let’s run through some common objections to econophysics models of income.

EXCHANGE IS NOT ‘RANDOM’

If I told you that your last monetary purchase was ‘random’, you would protest. That’s because you had a reason for purchasing what you did. When you gave money to Bob, it wasn’t because you ‘randomly’ bumped into him (as envisioned in econophysics world). It was because Bob was selling a car that you wanted to buy. So the effect (the exchange of money) had a definite cause (you wanted the car).

When econophysicists use ‘random exchange’ to explain income, many people are horrified by the lack of causality. It’s an understandable feeling — one that was actually shared (a century earlier) by Ludwig Boltzmann. A founder of statistical mechanics, Boltzmann was nonetheless tormented by his own theory. Like most physicists of the time, Boltzmann wanted his theory to be deterministic. (He thought effects should have definite causes.) Yet to understand the behavior of large groups of particles, Boltzmann was forced to use the mathematics of probability. The resulting uncertainty in cause and effect made him uneasy.4

Ultimately, Boltzmann’s unease was warranted. Quantum mechanics would later show that at the deepest level, nature is uncertain. But this quantum surprise does not mean that probability and determinism are always incompatible. In many cases, the use of probability is just a ‘hack’. It is a way to simplify a deterministic system that is otherwise too difficult to model.

A good example is a coin toss. When you toss a coin, most physicists believe it is a deterministic process. That’s because the equations that describe the toss (Newton’s laws), have strict cause and effect. Force causes acceleration. So if we had enough information about the coin and its environment, we could (in principle) predict the coin’s outcome.

The problem, though, is that in practice we don’t have enough information to make this prediction. So we resort to a ‘hack’. We realize that there only two possible outcomes for the coin: heads or tails. If the coin is balanced, both are equally probable. And so we model the coin toss as a random (non-deterministic) process, even though we believe that the underlying physics are deterministic.

Back to econophysics. When social scientists complain that econophysics models invoke ‘randomness’ to explain income and wealth, they are making a philosophical mistake. Econophysicists (correctly) respond that their models are consistent with determinism. When you spend money, you know exactly why you did it. But that doesn’t stop us from modeling your exchange with a statistical ‘hack’. Regardless of why you did it, the end result is that you spent money. So like a coin toss, econophysicists think we can treat monetary exchange in probabilistic terms. That’s a reasonable hypothesis — one that social scientists too readily dismiss.

WHERE IS THE PROPERTY?

In his article ‘Follow the money’, journalist Brian Hayes argues that econophysicists don’t model ‘exchange’ so much as they model theft. He has a point.

When you spend money, you usually get something back in return — namely property. That property could be a physical thing, as when you buy a car. Or it could be something less tangible, as when you buy shares in a corporation. But either way, the exchange is two sided. You lose money but gain property.5

In econophysics, however, there is no property. There is only money. So when you ‘bump’ into Bob (in econophysics world) and give him money, you get nothing in return. Of course, this type of one-sided transaction does happen in real life. But we don’t call it ‘exchange’. We use other words. If you gave the money to Bob, we call it a gift. Or if Bob just took the money, we call it theft. Either way, the gift/theft economy is a tiny part of all real-world monetary transactions. So it would seem that econophysics has a problem.

Or does it?

Econophysicists do not (to my knowledge) deny the importance of property. They just think we can model the exchange of money without understanding property transactions. Here’s why.

Regardless of what you bought from Bob, you leave the transaction with less money, he leaves with more money. We can lump the corresponding property transaction into the ‘causes that are too complex to understand’ column. Despite this (unexplained) complexity, the end result is still simple: money changes hands. Why can’t we model that transfer of money alone? Again, this is a reasonable hypothesis.

Bottoms up

Having defended econophysics models, it’s time for my critique. By appealing to statistical mechanics, econophysicists hypothesize that we can explain the workings of the economy from simple first principles. I think that is a mistake.

To see the mistake, I’ll return to Richard Feynman’s famous lecture on atomic theory. Towards the end of the talk, he observes that atomic theory is important because it is the basis for all other branches of science, including biology:

The most important hypothesis in all of biology, for example, is that everything that animals do, atoms do. In other words, there is nothing that living things do that cannot be understood from the point of view that they are made of atoms acting according to the laws of physics.

(Richard Feynman, Lectures on Physics)

I like this quote because it is profoundly correct. There is no fundamental difference (we believe) between animate and inanimate matter. It is all just atoms. That is an astonishing piece of knowledge.

It is also, in an important sense, astonishingly useless. Imagine that a behavioral biologist complains to you that baboon behavior is difficult to predict. You console her by saying, “Don’t worry, everything that animals do, atoms do.” You are perfectly correct … and completely unhelpful.

Your acerbic quip illustrates an important asymmetry in science. Reduction does not imply resynthesis. As a particle physicist, Richard Feynman was concerned with reduction — taking animals and reducing them to atoms. But to be useful to our behavioral biologist, this reduction must be reversed. We must take atoms and resynthesize animals.

The problem is that this resynthesis is over our heads … vastly so. We can take atoms and resynthesize large molecules. But the rest (DNA, cells, organs, animals) is out of reach. When large clumps of matter interact for billions of years, weird and unpredictable things happen. That is what physicist Philip Anderson meant when he said ‘more is different’.

Back to statistical mechanics. Here we have an example where resynthesis was possible. To develop statistical mechanics, physicists first reduced matter to particles. Then they used particle theory to resynthesize macro properties of matter, such as temperature and pressure. That this resynthesis worked is a triumph of science. But the success came with a cost.

In all fairness to Maxwell and Boltzmann, their equations describe systems that are utterly boring. The math applies to an ideal gas in thermal equilibrium. At the micro scale, there’s lots going on. But at the macro scale, literally nothing happens. The gas just sits there like a placid lake on a windless day. Boring.6

Water, reduced and resynthesized

When we move beyond ideal gases in thermal equilibrium, the mathematics of resynthesis quickly become intractable. Let’s use water as an example, and try to resynthesize it from the bottom up.

At the most fundamental level, water is described by quantum mechanics. According to this theory, chemistry reduces to the bonding of electrons between atoms. We can use this ‘quantum chemistry’ to predict properties of the water molecule (H2O), such as the bond angle between the two hydrogen atoms. We can also predict that, because of this bond angle, the water molecule will have electric poles. These poles cause water molecules to attract one another, a fact that explains properties of water like its surface tension and viscosity.

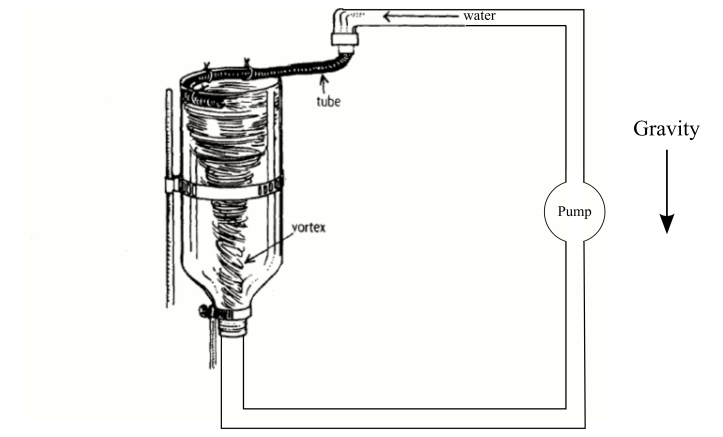

When we move to larger-scale properties of water, however, we have to leave quantum mechanics behind. Suppose we want to explain a simple vortex, as shown in Figure 2. To create the vortex, all you need is a tube filled with water and a hole in the bottom. Pull the plug and a vortex will form. (We add the pump to sustain the system.) Now the question is, how do we explain the whirlpool?

Quantum physics is no help. It’s a computational chore to simulate the properties of a single water molecule. But our vortex contains about 1024 molecules. So quantum physics is out.

What about statistical mechanics? It’s not helpful either. Physicists like Maxwell and Boltzmann made headway explaining the properties of gases, because when matter is in this state it’s valid to treat molecules like billiard balls. But in a liquid, this assumption breaks down. Rather than a diffuse cloud of billiard balls, a liquid is analogous to a ball-pit filled with magnetized spheres. The molecules don’t zoom around freely. They roil around in a haze of mutual attraction. It’s a mess.

So to make headway modeling our vortex, we abandon particle theory and turn to a higher-level approach. We treat water as a continuous liquid, defined by macro-level properties such as density and viscosity. We determine these properties from experiment, and then plug them into the equations of fluid dynamics. If we have enough computational power, we can simulate our vortex.

To model larger systems, we need still more computational power. Climate models, for instance, are basically large fluid-dynamics simulations. Presently, such models cannot resolve weather below distances scales of 100 km. Doing so would take too long on even the fastest supercomputers.

Back to water. The point of this story is to show the difficulty of resynthesis. We cannot take water molecules and resynthesize the ocean. Doing so is computationally intractable. So we introduce hacks. We do a partial resynthesis — water molecules to properties of water. We then put these properties in simpler equations to simulate the macro-level behavior of water.

This partial resynthesis is an important achievement. But it pales to what we ultimately wish to do. In a famous segment from Cosmos, Carl Sagan depicts the evolution of life from primordial ooze to humans. He concludes by noting: “those are some of the things that molecules do given four billion years of evolution.”

Sagan’s evolution sequence illustrates the scale of the resynthesis problem. We can easily reduce life to its constituents — primarily water and carbon. And yet we cannot take these components and resynthesize life. Unlike with water alone, with life there are no simplifying hacks that allow us to get from molecules to mammals. That’s because in mammals, the fine-scale structure defies simplification. Baboons are mostly sacks of water. But modeling them as such won’t explain their behavior. If it did, we would not have behavioral biology. We would have behavior fluid dynamics.

A foolhardy resynthesis

Social scientists often rail against the plight of ‘reductionism’. I think this is a mistake. To understand a complex system, we have no choice but to reduce it to simpler components. But that’s just the first step. Next, we must understand the connections between components, and use these connections to resynthesize the system. It is this second step that is filled with pitfalls. So when social scientists critisize ‘reductionism’, I think they are really criticizing ‘foolhardy resynthesis’.

And that brings me back to econophysics. When social scientists hear that econophysicists reduce humans to ‘particles exchanging money’, they are horrified. But when you have a close look at this reduction (as I have above), it’s not so terrible. Certainly humans are more complicated than molecules. But we do exchange money much like molecules exchange energy. The physicists who developed statistical mechanics were able to take energy-exchanging particles and resynthesize the properties of ideal gases. Why, say econophysicists, can’t we do the same with humans? Why can’t we take simple principles of individual exchange and resynthesize the economy?

The problem is that by invoking the mathematics of ideal gases, econophysicists vastly underestimate the task at hand. Explaining the human economy from the bottom up is not like using particle theory to explain the temperature of a gas. It is like using particle theory to explain animal metabolism.

Let’s dig deeper into this metaphor. We can certainly reduce metabolism to energy transactions among molecules. But if you try using these transactions to deduce (from first principles) the detailed properties metabolism, you won’t get far. The reason is that animal metabolism involves an ordered exchange of energy, defined by complex interconnections between molecules. Sure, the chemical formula for respiration is simple. (It’s just oxidizing sugar.) But when you look at the actually mechanisms used in cells, they’re marvellously complex. (Check out the electron transport chain, the machine that drives cellular respiration.)

What econophysicists are trying to do, in essence, is predict the properties of animal metabolism using the physics of ideal gases. The problem is not the reduction to energy exchange between molecules. The problem is a foolhardy resynthesis. In gases, the exchange of energy is unordered. So we can resynthesize properties of the gas using simple statistics. But we cannot apply this thinking to animal metabolism. When you ignore the ordered connections that define metabolism, you resynthesize not an animal, but an amorphous gas.

Money metabolism

The metaphor of metabolism is helpful for understanding where econophysicists go wrong in their model of the economy. Take, as an example, the act of eating.

Suppose a baboon puts a piece of fruit in its mouth. What happens next is a series of energy transactions. We might think, naively, that we can understand these transactions using the physics of diffusion. So when the fruit hits the baboon’s tongue, the energy in the fruit starts to ‘diffuse’ into the tongue. Unfortunately, that is not how metabolism works. The fruit touches the baboon’s tongue, yes. But the tongue cells don’t get any energy (yet). Instead, the tongue passes the fruit down the throat, where a long and complicated series of energy transactions ensue (digestion, circulation, respiration). Eventually, some of the fruit’s energy makes it back to the cells of the tongue. But the route is anything but simple.

Something similar holds in the human economy. Suppose you want to buy a banana. One option would be to purchase the fruit from your neighbor. If you do, things are much as they appear in econophysics models. You ‘bump’ into your neighbor Bob, and give him $1. He gives you a banana. It’s a particle-like transaction.

The problem is that (almost) nobody buys fruit from their neighbors. If you want a fruit, what you actually do is go to a grocery store … say Walmart. And there the transaction is different.

True, in the Walmart things start out the same. You find some bananas and head to the check out. There you meet Alice the cashier. You give her money, she lets you leave with the bananas. It’s still a particle-like transaction, right?

Actually no. The problem is that when you hand your money to Alice the cashier, it’s not hers to keep. The hand-to-hand transfer of cash is purely symbolic. As soon as Alice receives the money, she puts it in the cash register.7 Later, a low-level manager collects the cash and deposits it in a Walmart bank account. From there, mid-level managers distribute the money, working on orders from upper management. Eventually, some of your money may end up back in Alice’s hands (as a pay check). But the route is anything but simple.

Think of this route as ‘money metabolism’. Alice ‘touches’ your money much like tongue cells ‘touch’ the energy in food. But like the tongue cells, which simply pass the food down the digestive tract, Alice passes your money into Walmart’s ‘accounting tract’. As with the food energy, the result is a complex web of transactions governed by many layers of organization.

Yes, you can cut out this organization and observe that the end result is that money changes hands. But that’s like taking animal metabolism and reducing it to diffusion. When you cut out the details, you effectively convert the organism to a placid pool of matter. Similarly, when you cut out the ordered web of transactions that occur within organizations, you convert the economy to an inert gas. It is a foolhardy resynthesis.

Resynthesizing mud

Many econophysicists will grant that their models oversimplify the economy. But they will defend this simplification on the grounds that it ‘works’. Their models reproduce, with reasonable accuracy, the observed distribution of income.

The appropriate response should be “Good, your model passes the first test. Now open the hood and keep testing.” The problem is that econophysicists often do not keep testing. They are content with their ‘good results’.8

To see why this is a bad idea, let’s use an absurd example. Suppose that a biology lab is trying to synthesize life. The scientists combine elements in a test tube, add some catalysts, and then look at the result. They first test if the atomic composition is correct. They look at the abundance of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen to see if it is consistent with life. Lo and behold, they find that the test tube has the same atomic composition as humans!

“We’ve synthesized a human!” a lab tech shouts euphorically. The other scientists are less optimistic. “We’d better do more tests,” they caution. Their skepticism is well founded. Looking further, they see that the test tube contains no tiny human. It contains no organs, no cells, no DNA. It’s the right composition of elements, yes. But the test tube contains nothing but mud.

Kinetic exchange models of income/wealth, it pains me to say, are the equivalent of mud. Yes, these models replicate the macro-level distribution of income and wealth. But they ignore all other social structure. That’s okay, so long as the model is just a stepping stone. But the tendency in econophysics is say: “Look! My kinetic-exchange model reproduces the distribution of income. Therefore, inequality stems inevitably from the laws of thermodynamics.”

Sure … just like humans stem inevitably from mud.

How far down?

One of the central tenets of the scientific worldview is that the universe has no maker. It is a system that has self assembled. The consequence of this worldview (if it is correct) is that complexity must have arisen from the bottom up. After the Big Bang, energy condensed to atoms, which formed molecules, which formed proteins, which formed cells, which formed humans, who formed global economies. (For an epic telling of this story, see Eric Chaisson’s book Cosmic Evolution.)

The ultimate goal of science is to understand all of this structure from the bottom up. It is a monumental task. The easy part (which is still difficult) is to reduce the complex to the simple. The harder part is to take the simple parts and resynthesize the system. Often when we resynthesize, we fail spectacularly.

Economics is a good example of this failure. To be sure, the human economy is a difficult thing to understand. So there is no shame when our models fail. Still, there is a philosophical problem that hampers economics. Economists want to reduce the economy to ‘micro-foundations’ — simple principles that describe how individuals behave. Then economists want to use these principles to resynthesize the economy. It is a fools errand. The system is far too complex, the interconnections too poorly understood.

I have picked on econophysics because its models have the advantage of being exceptional clear. Whereas mainstream economists obscure their assumptions in obtuse language, econophysicists are admirably explicit: “we assume humans behave like gas particles”. I admire this boldness, because it makes the pitfalls easier to see.

By throwing away ordered connections between individuals, econophysicists make the mathematics tractable. The problem is that it is these ordered connections — the complex relations between people — that define the economy. Throw them away and what you gain in mathematical traction, you lose in relevance. That’s because you are no longer describing the economy. You are describing an inert gas.

So what should we do instead? The solution to the resynthesis problem, in my view, is to lower our expectations. It is impossible, at present, to resynthesize the economy from individuals up. So we should try something else.9

Here we can take a hint from biology. To my knowledge, no biologist has ever proposed that organisms be understood from atomic ‘first principles’. That’s because thinking this way gets you nowhere. Instead, biologists have engaged in a series of ‘hacks’ to try to understand life. Each hack partially reconstructs the whole.

Biologists started with physiology, trying to understand the function of the organs of the body. Then they discovered cells, and tried to reconstruct how they worked. That led to the study of organelles, and eventually the discovery of molecular biology. Along the way, biologists tried to resynthesize larger systems from parts — bodies from organs, organs from cells, cells from organelles, etc. They met with partial success.

When economists try to reconstruct the economy from ‘micro principles’, they are doing the biological equivalent of resynthesizing mammals from molecules. (Yes, the human economy is that complex.) The way to make progress is to do what biologists did: take baby steps. First look at firms and governments to see how they behave. Look at the connections between these institutions. Then look inside these institutions and observe the connections among people. Resynthesize in small steps.10

As we try to ‘hack’ our way to a resynthesis, we will probably fail. But we will fail less badly than if we tried to resynthesize society from individuals up. And hopefully, from our failure we will learn something. That’s science.