The “Work Ethic” Hoax The story has been told that Martin Luther invented the doctrine of the “calling” and that John Calvin (“my friends call me Jean”) intensified it with his doctrine of predestination. Subsequent pastoral literature softened the predestination blow with the Protestant ethic that working hard and succeeding would show that you were one of the elect. Max Weber told that story. It was, of course, a fable. But that is beside the point. Max Weber’s fable wallowed in relative academic obscurity and sports clichés until… [wait for it]… 1971 when Dick Nixon dusted it off as a cudgel to bludgeon those folks driving around in their Welfare Cadillacs — we all know who they are — and the nattering nabobs of negativism enabling them.

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important: history, politics, US/Global Economics, work ethic

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

The “Work Ethic” Hoax

The story has been told that Martin Luther invented the doctrine of the “calling” and that John Calvin (“my friends call me Jean”) intensified it with his doctrine of predestination. Subsequent pastoral literature softened the predestination blow with the Protestant ethic that working hard and succeeding would show that you were one of the elect. Max Weber told that story.

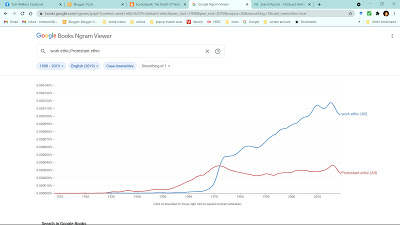

It was, of course, a fable. But that is beside the point. Max Weber’s fable wallowed in relative academic obscurity and sports clichés until… [wait for it]… 1971 when Dick Nixon dusted it off as a cudgel to bludgeon those folks driving around in their Welfare Cadillacs — we all know who they are — and the nattering nabobs of negativism enabling them. Pure backlash dog whistle.

“Keep religion out of it,” Nixon told a speechwriter who labeled it “the Protestant ethic” for a Labor Day address in 1971, “Let’s just call it the work ethic.”

I would like you to join me in exploring one of the basic elements that gives character to a people and which will make it possible for the American people to earn a generation of prosperity in peace.

Central to that character is the competitive spirit. That is the inner drive that for two centuries has made the American workingman unique in the world, that has enabled him to make this land the citadel of individual freedom and of opportunity.

The competitive spirit goes by many names. Most simply and directly, it is called the work ethic.

As the name implies, the work ethic holds that labor is good in itself; that a man or woman at work not only makes a contribution to his fellow man but becomes a better person by virtue of the act of working.

That work ethic is ingrained in the American character. That is why most of us consider it immoral to be lazy or slothful-even if a person is well off enough not to have to work or deliberately avoids work by going on welfare.

That work ethic is why Americans are considered an industrious, purposeful people, and why a poor nation of 3 million people, over a course of two centuries, lifted itself into the position of the most powerful and respected leader of the free world today.

Recently we have seen that work ethic come under attack. We hear voices saying that it is immoral or materialistic to strive for an ever-higher standard of living. We are told that the desire to get ahead must be curbed because it will leave others behind. We are told that it doesn’t matter whether America continues to be number one in the world economically and that we should resign ourselves to being number two or number three or even number four. We see some members of disadvantaged groups being told to take the welfare road rather than the road of hard work, self-reliance, and self-respect.

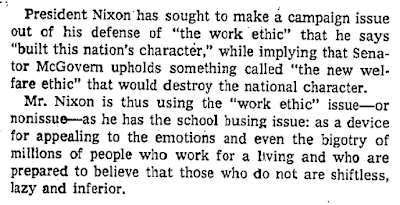

The New York Times was on to the hustle:

But the chattering classes couldn’t resist the work ethic mantra — pro or con.