Wealth is leisure. Leisure, wealth. The three quotes above are from, respectively: 1. William Godwin 2. Charles Wentworth Dilke 3. Karl Marx. There was a very pronounced influence of Godwin on Dilke and of Dilke on Marx (hence indirectly of Godwin on Marx). My research suggests that viewing Marx’s work from the perspective of Dilke’s major influence reveals both hidden strengths and weaknesses in Marx’s critique of political economy. The yellowed backgrounds are the title pages of Godwin’s Enquirer (1797), Dilke’s Source and Remedy of the National Difficulties (1821), and a page from Marx’s 1857-58 manuscripts, subsequently published as the Grundrisse. The difficulty of reading the background is my metaphor for the palimpsest of the

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important: Journalism, politics, US EConomics, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Wealth is leisure. Leisure, wealth.

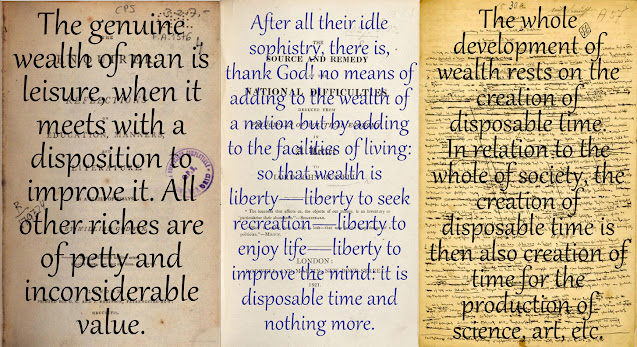

The three quotes above are from, respectively: 1. William Godwin 2. Charles Wentworth Dilke 3. Karl Marx. There was a very pronounced influence of Godwin on Dilke and of Dilke on Marx (hence indirectly of Godwin on Marx). My research suggests that viewing Marx’s work from the perspective of Dilke’s major influence reveals both hidden strengths and weaknesses in Marx’s critique of political economy.

The yellowed backgrounds are the title pages of Godwin’s Enquirer (1797), Dilke’s Source and Remedy of the National Difficulties (1821), and a page from Marx’s 1857-58 manuscripts, subsequently published as the Grundrisse. The difficulty of reading the background is my metaphor for the palimpsest of the successive generations of the text about wealth being leisure/disposable time. One of the conceptual problems we face is that the connotation of “leisure” has been drained of its original content of including — in fact enabling — culture, science and art. What may not be immediately apparent in these excerpts is that Godwin and Dilke treated leisure as the fruit of industry and productivity. Marx explicitly viewed disposable time as the precondition of industrial expansion, as well as an outcome of that expansion.

In three “fragments on machines” from the Grundrisse, Marx — or at least my idiosyncratic version of Marx — developed both the dark side and the emancipatory potential of the expansion of disposable time. For Marx, disposable time was truly ambivalent because the compulsion of capital is not only to expand disposable time but also to convert it into surplus value alienated from its producers.

Furthermore, the creation of surplus value becomes a condition for the employment of labour. To make a living, workers must meet a ‘means test’ that their labour generates surplus value for the employer. This is a condition that depends on the availability of fixed capital, raw materials and markets for the product of their work — all of which requirements workers have no control over.

Those requirements are also, provisionally, beyond the reach of the individual capitalist, who is thus compelled to actively pursue the conditions that will facilitate the creation of surplus value. The individual capitalist does this by improving productivity through technological improvement and thereby capturing a more profitable market share.

The pursuit of what Marx called relative surplus value both presupposes and perpetuates a reservoir of untapped labour power. Some of that additional labour power comes from expanding the hours of currently employed workers. This is why the average weekly hours data from the BLS can serve as an index of economic expansion. More “reserved” labour power is available from the ranks of the unemployed.

Note the italicized word, available. It is a synonym for one of the meanings of disposable. Unemployed workers who are available for work are a source of disposable labour time — thus a “disposable industrial reserve.”

In the three fragments on machines, Marx repeatedly contrasted necessary labour time with “the superfluous.” Sometimes the latter explicitly refers to superfluous labour time as a synonym for surplus labour time (producing surplus value). More often the noun is absent or ambiguous. The ambiguity, I suspect, was intentional. What is superfluous could refer to the labour time spent to create surplus value; it could refer to excess labour time resulting in overproduction; or it could refer to superfluous labour capacity, an unemployed surplus population. In actuality, it refers to all three at various stages of an industrial cycle of boom and bust.

‘Superfluous’ is sort of a synonym for ‘disposable’ but with more of a connotation of being out of control, chaotic, and potentially menacing. Disposable is more than enough. Superfluous is too much. Available is just the right amount, Goldilocks.

Readers familiar with Marx’s Capital may have noticed that the analysis from the three fragments I have summarized here subsequently found homes in chapters 10 and 25 of volume one, “The Working Day” and “The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation” and chapter 15 of volume three, “Internal Contradictions of the Law [of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall].” In journalism it is called “burying the lede.”

The point is, however, that there is nothing “natural” or “inevitable” about the appropriation by capital of disposable time in the form of surplus value. Nor is there anything natural or inevitable in the production and use by capital of a surplus population offering disposable labour time as a lever to ensure that the supply and demand for labour is perpetually favorable to capital.

The point is, finally, that the “antithetical existence” of disposable time in the form of surplus labour and surplus labour capacity is neither natural nor inevitable but in order to overcome the contradictions manifest in this antithesis, “the mass of workers must themselves appropriate their own surplus labour.”

Once they have done so – and disposable time thereby ceases to have an antithetical existence – then, on one side, necessary labour time will be measured by the needs of the social individual, and, on the other, the development of the power of social production will grow so rapidly that, even though production is now calculated for the wealth of all, disposable time will grow for all.

That last bit is a tall order indeed. An enlightened mass of workers acting in concert as the revolutionary subject is no more natural nor inevitable than alienated surplus value or the disposable industrial reserve army. It is a poetic image: “the slumbering giant awakens.” As William Godwin’s son-in-law, Percy, expressed it:Rise, like lions after slumberIn unvanquishable number!Shake your chains to earth like dewWhich in sleep had fallen on you:Ye are many—they are few!But at least we know what the stakes are. On the one hand, periodic economic crises staunched temporarily by government bailouts and cheap-credit asset inflation, ecological devastation, and social disintegration. On the other hand, art, science, liberty, and recreation. Tough choice.

Over the summer, I posted a series on Econospeak investigating Marx’s category of “socially necessary labour time” and its relationship to disposable time, surplus population and the superfluous (labour time, not-labour time, labour capacity, production, consumption). I have reworked my findings into a 10,000-word paper and a pop-up book. I expect to be doing a conference presentation on this material sometime in November.

I am hesitating to submit my 10,000 words to an academic journal. I would prefer a venue like the New Yorker, Harper’s or, even the Atlantic Monthly. With a commission and a good editor, I could make the piece accessible — even entertaining. Who would want to read a long, accessible, entertaining article about leisure and wealth vs. immiseration and alienation?