What follows is based on Erik S. Reinert’s book How Rich Countries Got Rich, and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor (2007), pp. 301–304.Ricardo’s famous example of cloth and wine production in Portugal and England (Ricardo 1819: 144–148) can be set out in the following table: Ricardo’s argument is simple: Portugal can produce more wine by concentrating on the production of that, and import cloth from England, even if (as in Ricardo’s example) it takes fewer labourers to produce cloth in Portugal than in England. The aggregate effect of England concentrating on producing cloth (where its comparative advantage lies owing to the lower opportunity cost) and Portugal producing wine is that a greater quantity of these commodities can be produced in total, and Portugal and England can exchange them to mutual benefit, instead of producing fewer goods in isolation and autarky.It is better, according to Ricardo, that each nation should specialise in the sector where it has comparative advantage, and then trade.But this is not necessarily true, once we relax the grossly unrealistic assumptions implicit in Ricardo’s thought experiment.For one thing, Ricardo has assumed that there are neither increasing nor diminishing returns to scale.

Topics:

Lord Keynes considers the following as important: Erik Reinert versus Ricardo on Free Trade

This could be interesting, too:

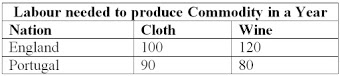

Ricardo’s famous example of cloth and wine production in Portugal and England (Ricardo 1819: 144–148) can be set out in the following table:

Ricardo’s argument is simple: Portugal can produce more wine by concentrating on the production of that, and import cloth from England, even if (as in Ricardo’s example) it takes fewer labourers to produce cloth in Portugal than in England. The aggregate effect of England concentrating on producing cloth (where its comparative advantage lies owing to the lower opportunity cost) and Portugal producing wine is that a greater quantity of these commodities can be produced in total, and Portugal and England can exchange them to mutual benefit, instead of producing fewer goods in isolation and autarky.

It is better, according to Ricardo, that each nation should specialise in the sector where it has comparative advantage, and then trade.

But this is not necessarily true, once we relax the grossly unrealistic assumptions implicit in Ricardo’s thought experiment.

For one thing, Ricardo has assumed that there are neither increasing nor diminishing returns to scale.

If Portugal concentrates on wine production (or indeed on any sector of the same type), it will get caught in a trap of diminishing returns and rising costs of production, and in the end will specialise in becoming poor as it fails to industrialise (Reinert 2007: 302).

And now we have a killer point that Erik Reinert makes against Ricardo’s argument:

“It is important to understand that … [sc. Ricardo’s] theory represents the world economy as a process of bartering of labour hours which are devoid of any skills or other characteristics. A labour hour in Silicon Valley equals a labour hour in a refugee camp in Darfur in the Sudan. Ironically, capitalist trade theory in its purest form does not consider the role of capital; instead it is based on the labour theory of value. Therefore it does not consider that one country’s production process might potentially absorb much knowledge and capital (like Microsoft's products) while the other country’s production process might remain highly labour-intensive, in processes where capital cannot profitably be employed … .” (Reinert 2007: 303).Remember that Ricardo was not a marginalist, but a Classical economist using the pre-Marxist labour theory of value.

Reinert has put his finger on a devastating point here: one of Ricardo’s crucial arguments in favour of free trade by comparative advantage is based on the idea that specialising in the production of some commodity is inherently better just because of the comparatively lower labour time involved in production. As Robinson pointed out:

“Ricardo’s analysis of comparative advantage is often misunderstood. The comparison is not between the costs of production, in money terms, of particular commodities at home and abroad; it is a comparison between the real costs (in terms of labour and other resources) of different commodities at home. The argument was that, when protection is taken off, resources will move from the production of commodities with high real costs (which can then be imported) to those with lower real costs so that their productivity is increased.” (Robinson 1979: 102–103).That this is a good thing, as Ricardo thought, doesn’t follow at all.

Even if it takes more labour hours and human labourers to produce manufactured goods, in the long run this is a key to becoming rich, whereas dead-end production of commodities with diminishing returns to scale, even if it requires fewer labour hours and labourers, is a path to Third World poverty.

Reinert (2007: 302–304) goes on to construct an example in which, under Ricardo’s principle of comparative advantage, Portugal should specialise in producing Stone age goods, while England specialises in industrial goods: the result is that the world economy might be better off by a larger, total number of goods, but the price is that Portugal must remain in the Stone age.

In essence, Ricardo’s argument ignores the long-run benefits of industrialisation, which is the only real way to escape the grinding rural poverty of underdevelopment – unless of course you are lucky enough to be one of the minority of nations that has lucrative commodities like energy, or to be some tiny city-state that can get by on service industries. In the long run, Portugal is better off producing cloth and other manufactured goods, not just wine.

Moreover, as Philip Pilkington points out here, violent swings in the demand for, and prices of, the primary commodities in which Third World nations are often supposed to have comparative advantage will cripple and destabilise these developing nations when their economies are so narrowly specialised in limited sectors.

The fact that Ricardo wrote before the full effects of the industrial revolution were apparent should alert us to the deficiencies of his argument too.

External Links

Philip Pilkington, “Arguments against Free Trade and Comparative Advantage,” Fixing the Economists, May 1, 2014.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Reinert, Erik S. 2007. How Rich Countries Got Rich, and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor. Carroll & Graf, New York.

Ricardo, David. 1819. On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation (2nd edn.). John Murray, London.

Robinson, Joan. 1979. Aspects of Development and Underdevelopment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York.