From David Ruccio This was supposed to be the great reset. As the U.S. economy recovered from the Pandemic Depression, millions of jobs were being created, unemployment was falling, and the balance of power between workers and capitalists would shift toward wage-earners and against their employers. That, at least, was the promise (or, for capitalists, the fear). But greedflation has delivered exactly the opposite: workers’ real wages are barely rising while corporate profits are soaring. There’s been no reset at all. That’s exactly what was happening before the coronavirus pandemic hit, and that trend has only continued during the recovery. It should come as no surprise then that the already grotesque levels of inequality in the United States continue to worsen. And who are the

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

This was supposed to be the great reset. As the U.S. economy recovered from the Pandemic Depression, millions of jobs were being created, unemployment was falling, and the balance of power between workers and capitalists would shift toward wage-earners and against their employers.

That, at least, was the promise (or, for capitalists, the fear).

But greedflation has delivered exactly the opposite: workers’ real wages are barely rising while corporate profits are soaring. There’s been no reset at all. That’s exactly what was happening before the coronavirus pandemic hit, and that trend has only continued during the recovery. It should come as no surprise then that the already grotesque levels of inequality in the United States continue to worsen.

And who are the beneficiaries? According to a recent study by the Institute for Policy Studies, it’s the Chief Executive Officers of American corporations who have managed to capture a large share of the resulting surplus.

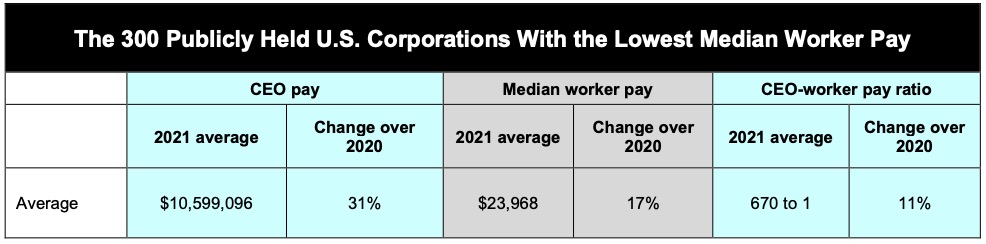

Especially the CEOs of the largest low-wage employers in the United States. While median worker pay increased by 17 percent last year, CEO compensation rose by 31 percent. The result was that the ratio of CEO to average worker pay rose by 11 percent, to 670 to 1!*

American workers are struggling with rising prices, having risked their lives and livelihoods throughout the pandemic. Now, they’re forced to watch as their corporate employers, who have benefited from federal contracts and used their profits to buyback stocks, reward their CEOs with lucrative contracts and massive bonuses—far exceeding the small amount some workers have been able to claw back.

Who’s at the top? Amazon leads the list. Its new CEO, Andy Jassy, raked in $212.7 million last year, which amounts to 6,474 times the pay of Amazon’s median 2021 worker. Then there’s Estee Lauder’s CEO, Fabrizio Fred, who managed to secure a 258-percent pay increase in 2021—leading to compensation that amounted to 1,965 times that of the average worker. Third on the list was the CEO of Penn National Gaming, Jay Snowden, whose $65.9 million payout was 1,942 times that of the gambler’s typical worker’s wage.

So, how did they manage to capture so much surplus and distribute it to their CEOs? Like the other firms in the study, they all took the low road, paying their employees a pittance (in the low $30,000s for the median worker). And they’ve mostly succeeded in opposing and undermining union-organizing efforts.** But Amazon is the only one of the three to secure large federal contracts (over $10 billion between 1 October 2019 and 1 May 2022), like other low-wage corporations (such as Maximus, at $12.3 billion and TE Connectivity, at $3.3 billion), which means the taxes paid by ordinary Americans and being used to support such an inequitable corporate order.***

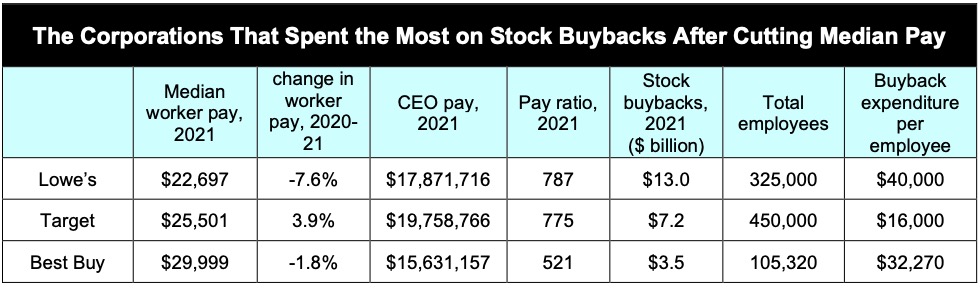

The report also highlights the extent of stock buybacks—which serve to inflate the value of a company’s shares and thus the value of executives’ stock-based compensation—among firms where median worker pay did not keep pace with inflation in 2021. Thus, for example, Lowe’s, the home-improvement chain, spent more than $13 billion in purchasing its own stock while median worker compensation fell by 7.6 percent to $22,697. Similarly, both Target and Best Buy increased workers’ pay by less than the rate of inflation but still spent millions of dollars in stock buybacks ($7.2 billion and $3.5 billion, respectively). In each case, a windfall to stock owners—including the CEOs—came at the expense of raises for the employees. For example, if the funds Lowe’s used to buyback its own stock had been divided among the company’s 325,000 employees, each worker would have received a $40,000 bonus.

Clearly, this economic order needs a fundamental reset.

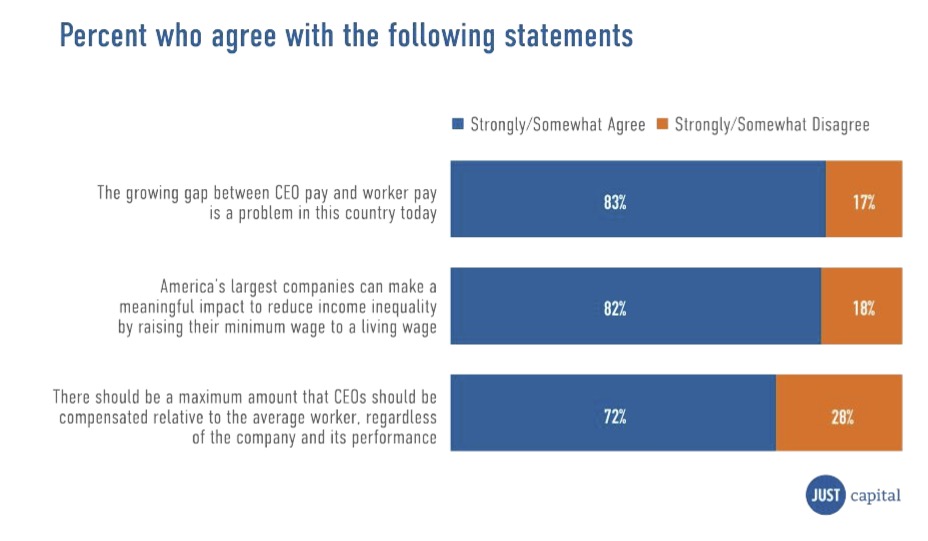

And most Americans agree. According to a recent survey by Just Capital (pdf), more than eight in 10 respondents (83%) agree that the growing gap between CEO compensation and worker pay is a problem in the United States today. Moreover, according to the authors,

The message from the public is clear: responsibility lies with corporate leaders – including chief executives – to address income inequality in America today. Closing the gap requires action at the highest and lowest rungs of the corporate ladder.

The IPS suggests a range of options for doing something about the problem, including giving corporations with narrow pay ratios preferential treatment in government contracting, an excessive CEO pay tax, and a ban on stock buybacks (in addition to a wide variety of CEO pay reforms). If enacted, all such changes would serve to nudge such corporations out of the low road of poor worker pay and high CEO compensation and reduce the now-obscene level of inequality in the U.S. economy.

But giving employees a say in how those corporations are managed and operated would do even more to change the balance of power, within those firms and the entire economy, between workers and capitalists. The workers would then be able to participate in deciding how much surplus there would be and how it would be utilized—not only for their benefit but for the society as a whole.**** Employees would then become or participate in choosing the corporate leaders, including chief executives, who could actually go a long way toward solving the problem of inequality in America today.

That, in my view, is a reset of the U.S. economy worth imagining and enacting.

———

*Forty-nine of the 300 firms analyzed by the Economic Policy Institute had ratios above 1000-1. And, in 106 companies in their sample, median worker did not keep pace with the 4.7 percent average U.S. inflation rate in 2021.

**Amazon has spent millions of dollars in fighting union campaigns and, to date, have lost only one battle, in a Staten Island warehouse. (That’s in the United States. Some Amazon warehouses in Europe are unionized, with strikes being most frequent in Germany, Italy, Poland, France and Spain.) None of Estee Lauder’s U.S. workers have union representation, and less than 20 percent of Penn’s employees are unionized.

***Of the 300 companies in the IPS study, 119 — 40 percent — received federal contracts, totaling $37.2 billion. Their average CEO-worker pay ratio was 571-to-1 in 2021.

****Even Thomas Piketty now defends the idea of workplace democracy or co-determination, since workers “sometimes, they are more serious and committed long-run investors than many of the short-term financial investors that we see. And so getting them to be involved in defining the long-run investment strategy of the company can be good.”