From Lars Syll In 1817 David Ricardo presented — in Principles — a theory that was meant to explain why countries trade and, based on the concept of opportunity cost, how the pattern of export and import is ruled by countries exporting goods in which they have a comparative advantage and importing goods in which they have a comparative disadvantage. Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage, however, didn’t explain why the comparative advantage was the way it was. At the beginning of the 20th century, two Swedish economists — Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin — presented a theory/model/theorem according to which the comparative advantages arose from differences in factor endowments between countries. Countries have comparative advantages in producing goods that use up production factors

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Lars Syll

In 1817 David Ricardo presented — in Principles — a theory that was meant to explain why countries trade and, based on the concept of opportunity cost, how the pattern of export and import is ruled by countries exporting goods in which they have a comparative advantage and importing goods in which they have a comparative disadvantage.

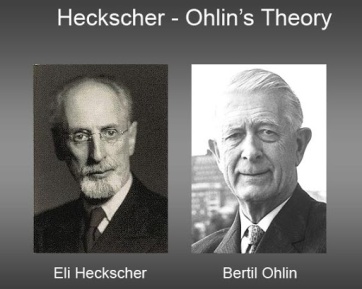

Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage, however, didn’t explain why the comparative advantage was the way it was. At the beginning of the 20th century, two Swedish economists — Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin — presented a theory/model/theorem according to which the comparative advantages arose from differences in factor endowments between countries. Countries have comparative advantages in producing goods that use up production factors that are most abundant in the different countries. Countries would mostly export goods that used the abundant factors of production and import goods that mostly used factors of production that were scarce.

Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage, however, didn’t explain why the comparative advantage was the way it was. At the beginning of the 20th century, two Swedish economists — Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin — presented a theory/model/theorem according to which the comparative advantages arose from differences in factor endowments between countries. Countries have comparative advantages in producing goods that use up production factors that are most abundant in the different countries. Countries would mostly export goods that used the abundant factors of production and import goods that mostly used factors of production that were scarce.

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem — as do the elaborations on in it by e.g. Vanek, Stolper and Samuelson — builds on a series of restrictive and unrealistic assumptions. The most critically important — besides the standard market-clearing equilibrium assumptions — are

— Countries use identical production technologies.

— Production takes place with constant returns to scale technology.

— Within countries, the factor substitutability is more or less infinite.

— Factor prices are equalised (the Stolper-Samuelson extension of the theorem).

These assumptions are, as almost all empirical testing of the theorem has shown, totally unrealistic. That is, they are empirically false.

That said, one could indeed wonder why on earth anyone should be interested in applying this theorem to real-world situations. Like so many other mainstream mathematical models taught to economics students today, this theorem has very little to do with the real world.

Since Ricardo’s days, the assumption of internationally immobile factors of production has been made totally untenable in our globalised world. When our modern corporations maximize their profits they do it by moving capital and technologies to where it is cheapest to produce.

So we’re actually in a situation today where absolute — not comparative — advantages rule the roost when it comes to free trade.

And in that world, what is good for corporations is not necessarily good for nations.