– Sandwichman @ Econospeak The Unbearable Tightness of Peaking Sandwichman came across a fascinating and disconcerting new dissertation, titled “Carbon Purgatory: The Dysfunctional Political Economy of Oil During the Renewable Energy Transition” by Gabe Eckhouse. An adaptation of one of the chapters, dealing with fracking, was published in Geoforum in 2021 As some of you may know, the specter of Peak Oil was allegedly “vanquished” by the invention of methods for extracting “unconventional oil” from shale formations (or “tight oil”), bitumen sands, and deep ocean drilling. A large part of that story was artificially low interest rates in response to the stock market crash of 2008 and subsequent recession. What Eckhouse’s dissertation and

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important: climate change, fracking, Hot Topics, Oil, peak oil, politics, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

– Sandwichman @ Econospeak

The Unbearable Tightness of Peaking

Sandwichman came across a fascinating and disconcerting new dissertation, titled “Carbon Purgatory: The Dysfunctional Political Economy of Oil During the Renewable Energy Transition” by Gabe Eckhouse. An adaptation of one of the chapters, dealing with fracking, was published in Geoforum in 2021

As some of you may know, the specter of Peak Oil was allegedly “vanquished” by the invention of methods for extracting “unconventional oil” from shale formations (or “tight oil”), bitumen sands, and deep ocean drilling. A large part of that story was artificially low interest rates in response to the stock market crash of 2008 and subsequent recession.

What Eckhouse’s dissertation and article explain is the flexibility advantage that fracking provides because the investment required for a well is two orders of magnitude less than for exploiting a conventional field and the payback time is much shorter. The downside is that the cost per barrel of the oil is much higher. Until now loose monetary policy has buffered that cost differential.

The strategic advantage of fracking, combined with the volatility of oil prices over the past two decades and uncertainty about possible future government decarbonization policies (what oil industry figures are ironically calling “peak oil demand”) are making large, long-term investments in conventional oil extraction — investments of the order of, say, $20 trillion over the next quarter century — less attractive.

Although the latter might sound like a good thing, what it implies is a full-blown energy crisis occurring much earlier than any purported transition to renewable non-carbon energy sources. I wouldn’t be surprised to see reactionary politicians and media agitate a “populist” movement to scapegoat “climate-woke” activists and scientists as saboteurs responsible for “cancelling” long-term investment in a cheap oil economy.

I had forgotten the oil price rise of 2007-08 when a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude rose from $85 in January 2007 to $125 in November to $156 in April 2008 to $190 in June. Now I remember my sense of awe at the time and dread that something really, really bad was soon going to happen to “the economy.” But then nothing happened. Nothing, that is, but the collapse of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, a stock market crash, emergency bank bailouts, and subsequent central bank monetary policy of low, low interest rates. But “the fundamentals were sound.”

It scrambles my brain trying to distinguish cause from effect. Did the ultra-low post 2008 crash low interest rates incidentally drive the subsequent fracking boom? Or was specifically a fracking boom one of the core objectives of the low interest rate regime?

Whither “peak oil”? According to Laherrère, Hall, and Bentley in How much oil remains for the world to produce? (2022) “the end of cheap oil” did not go away when the oil can was kicked down the road:

Our results suggest that global production of conventional oil, which has been at a resource-limited plateau since 2005, is now in decline, or will decline soon. This switch from production plateau to decline is expected to place increasing strains on the global economy, exacerbated by the generally lower energy returns of the non-conventional oils and other liquids on which the global economy is increasingly dependent.

If we add to conventional oil production that of light-tight (‘fracked’) oil, our analysis suggests that the corresponding resource-limited production peak will occur soon, between perhaps 2022 to 2025.

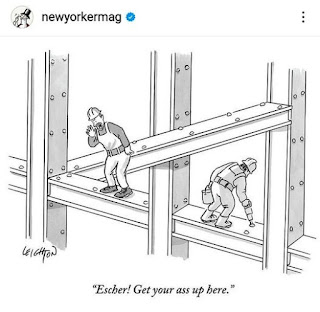

Including “all liquids” pushes that horizon out to 2040. In short, we overshot peak oil by a couple decades with the aid of loose money and tight oil, with a little additional help from the Covid pandemic. Those of us with a memory longer than the news cycle may recall that the current round of interest rate hikes by the Fed was initiated in response to inflation, which reached a 40-year high in June of last year due to record gasoline prices. Lower demand for gasoline brings down gas prices while higher interest rates may discourage new investment in fracking posing the specter of an oil supply crunch a couple of years down the road.The cartoon below illustrates the loose money/tight oil — tight money/peak oil dilemma: