On this blog, I’ve stated that economics needs a ‘periodic table of prices’. There are many different prices beyond ‘market prices’: Cost prices, Administrated prices, Government prices, Factor prices and whatever. We need a grid which enables a classification. As I, clearly, do not seem to be your average inspiring charismatic direction setting economists, nobody followed up on my statements…. With this blog, I want to start my journey towards the framework, to boldly go from where people like Frederic Lee, Philip Pilkinton and Gyun Cheol Gu have brought us. More about them in later blogs. Today (and in two blogs to follow): the prices which I encounter in my own research. I’ll focus on three topics: multi factor pricing of milk, risk free (not) interest rates and cost-, market,

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

On this blog, I’ve stated that economics needs a ‘periodic table of prices’. There are many different prices beyond ‘market prices’: Cost prices, Administrated prices, Government prices, Factor prices and whatever. We need a grid which enables a classification. As I, clearly, do not seem to be your average inspiring charismatic direction setting economists, nobody followed up on my statements…. With this blog, I want to start my journey towards the framework, to boldly go from where people like Frederic Lee, Philip Pilkinton and Gyun Cheol Gu have brought us. More about them in later blogs. Today (and in two blogs to follow): the prices which I encounter in my own research.

I’ll focus on three topics: multi factor pricing of milk, risk free (not) interest rates and cost-, market, insurance and liquidation prices of hay. What kind of prices did I encounter? Just market prices – or is there more to exchange that just markets? To answer this, we first have to define market prices.

In a market, there are generally three prices. A bidding price, an asking price and the selling price, which, rather unusually when it comes to prices, is set before a transaction is finalized. Procedures (institutionalized haggling) to arrive at the transaction price can be almost non-existent (as in a supermarket) or consist of elaborate rituals (as in the case of a large building project). But both sides can say no, meaning that both sides can forestall the final transaction. The selling price is, generally, called the ‘market price’ of a service or a commodity and can be higher or lower than the cost price. A market price is not the same as an ‘administered price’, which is defined, on ‘Investopedia‘, as “An administered price is one that is decreed by some authority for a good or service, rather than through a process of price discovery in a free market“. Investopedia restricts this authority to the state but it can very well also be a (staff department) of a company or, as Wikipedia states (citing Gardiner Means, who developed the concept), “Administered prices are prices of goods set by the internal pricing structures of firms that take into account cost rather than through the market forces of supply and demand[1] and predicted by classical economics. They were first described by institutional economists Gardiner Means and Adolf A. Berle in their 1932 book The Modern Corporation and Private Property. As Means argued in 1972, “Basically, the administered-price thesis holds that a large body of industrial prices do not behave in the fashion that classical theory would lead one to expect“”. We’ll see this in the case of multi component pricing of milk. But today: the ‘risk free (not) rate’. Beware: before being able to even tentatively define the nature of the prices I encountered, quite some institutional details have to be explained. ‘Some authority’, to use the Investopedia phrase, presupposes ‘the other side’ and we will have to know the nature of the relation between these parties. The graph is not too much to my liking, but for whatever reason the graph function in Excel malfunctioned and after wasting too much time I decided to leave it like this.

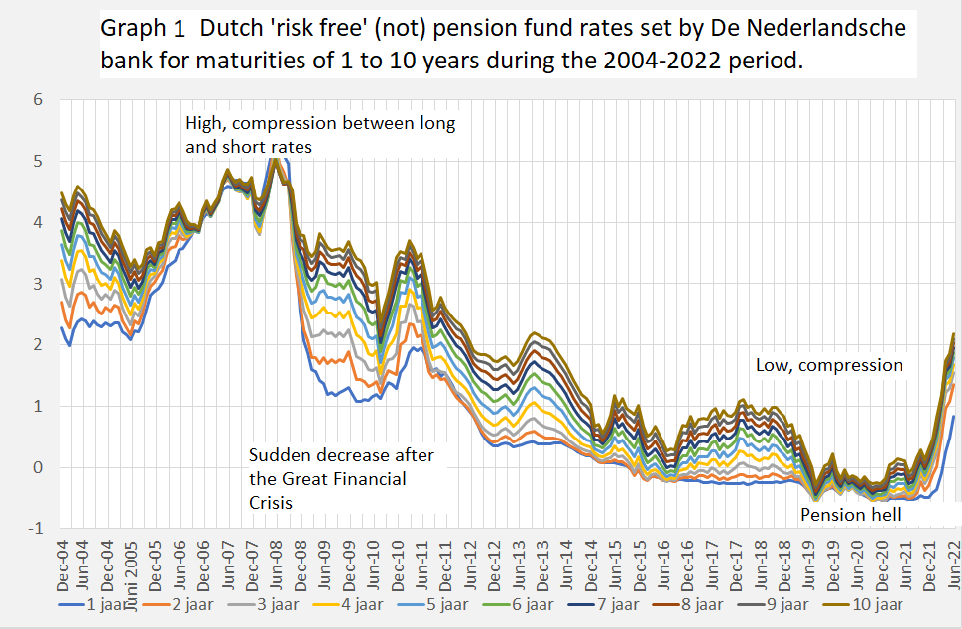

The (Dutch) Risk Rree (not) Rate. This is the rate Dutch pension funds have to use to discount their future pension expenditures. If the rate is high, future expenditures will loom small. If the rate is low, future expenditures will loom large. First, the graph. As we see, it’s not one rate but a number of rates, the ‘risk free rate’ is (can be) different for 1 year liabilities, 2 years liabilities etcetera. The spread between short and long is remarkably variable while the average goes from +5% to -0,5%. This decline is a big deal as this is compound interest: 5% in year 1 plus 5% in year to adds (multiplies) to a total discount factor of 10,25 in two years, while rates of -0,5 multiply to a negative discount factor of -1% in year two – more about discounting below. Meaning that future expenditures two year from now will loom 10,25 smaller in the 5% case and 1% larger in the -0,5% case. Do the math for 10 years…

The authority which sets the Risk Free (not) Rate is De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), or the Dutch Central Bank. Pension funds are obliged to use it. These pension funds are non-profits, or ‘NPISH’ in the parlance of the national accounts, Non Profit Institutions Serving Households. Dutch households can’t withdraw their pension asset (it’s not an amount of money, it’s the right to a pension income till the day you die, an insurance). Unless they change jobs, people can’t switch funds. This means that the pension funds have extremely long liabilities (unlike banks). However, the DNB, worngly, implicitly assumes that people can withdraw their insurance at very short notice. Meaning that, according to DNB, the funds must be able at all times to finance a total withdrawal of funds by members of the funds (a pension fund run), even when this is institutionally impossible. This means that the assets are valued at market prices. And liabilities are discounted with the implicit interest rate on government bonds, even when the funds can, as liabilities are to an extent extremely long (up to 60 and 70 years) easily hold even 20 year government bonds to maturity (if they’re smart enough to have a mix of long term and short term bonds). By using them as a discount factor they automatically also become future return of investment predictors. But that’s not how the Dutch risk free (not) rate is designed. It is designed to calculate if funds can withstand an pension fund run. And even when the rate necessarily doubles as a predictor of future returns on investments, it is not designed to do this and it’s actually a rather bad predictor. Combined with the fact that, for pension funds, there is no need to use a risk free rate which might be good for banks (where people can withdraw deposits at short order) this means that it led to havoc in the pension system. Funds should not use the completely ridiculous idea that assets (including stocks and real estate) will yield negative nominal yields of -0,5% during their entire lifetime (the implication of the graph during the period of ‘pension hell’). That just does not happen. Funds were however forced to use this assumption, leading to overly high premiums, a whopping current account surplus on the Dutch current account (as people did not spend the money and funds did not really invest in the real economy but purchased foreign financial assets). But the point: what kind of price is this risk free rate? There clearly is an authority setting the rate (DNB). Funds are forced to use it. And people are obligatory members of sectoral funds. Meaning that this is a government-NPISH administered price in the sense of Gardiner Means, against a background of obligatory membership of sectoral funds and obligatory premiums. Not a market. But a price. Which leads to some parts of the framework: governments, NPISH and households. And the idea that designing administered prices should be done in a careful way – more careful than neoclassical economists are able to do. Next time: the ‘fair value’ of milk.