History Rhymes Again – Civil Discourse, Joyce Vance, substack.com. Just over 60 years ago, Alabama’s segregationist governor, George Wallace, made his infamous stand in the schoolhouse door, barring the path against court-ordered integration at the state’s flagship university. It was June 11, 1963. Wallace, in his inaugural address, had promised voters “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” But Wallace’s defiance failed in the face of the rule of law. He ultimately stepped aside to permit the first two Black students at the university to enroll. In a 1978 case, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court held that college admissions policies that considered race as one of several factors in

Topics:

run75441 considers the following as important: 2023, affirmative action, Education, Journalism, law, politics, SCOTUS

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

History Rhymes Again – Civil Discourse, Joyce Vance, substack.com.

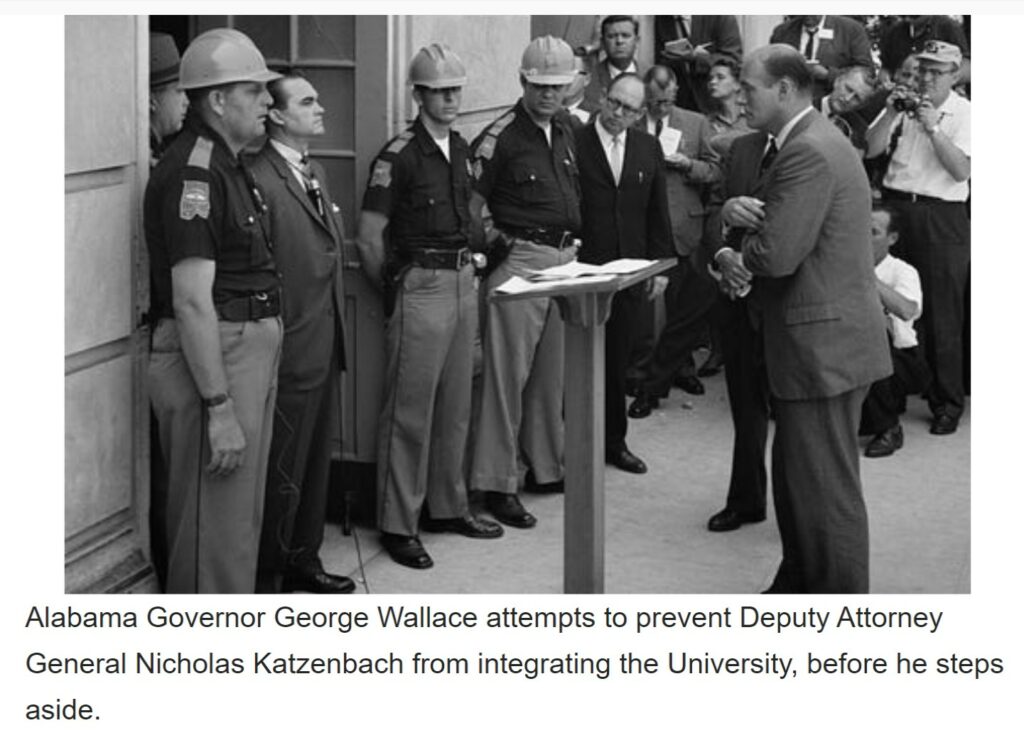

Just over 60 years ago, Alabama’s segregationist governor, George Wallace, made his infamous stand in the schoolhouse door, barring the path against court-ordered integration at the state’s flagship university. It was June 11, 1963. Wallace, in his inaugural address, had promised voters “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

But Wallace’s defiance failed in the face of the rule of law. He ultimately stepped aside to permit the first two Black students at the university to enroll.

In a 1978 case, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court held that college admissions policies that considered race as one of several factors in determining admissions—what we know as affirmative action—were permissible. The justices rejected the argument that these policies violated the constitutional rights of white people and denied them equal educational opportunity. The Supreme Court reaffirmed this precedent in 2003 in Grutter v. Bollinger.

Affirmative action is not about unfair advantage. It is about leveling the playing field in the face of historical discrimination. And despite what the Supreme Court said this morning in a pair of cases ending the use of affirmative action in admissions policies, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, our playing field is not level yet.

I teach at the University of Alabama’s Law School. I’m proud to have the opportunity to teach at a law school where affirmative active policies have helped to develop more diverse classes, full of amazing, smart, engaged students who go on to be the kinds of lawyers our communities need. Some of them come from backgrounds that made it challenging to arrive where they are today. But with a strong education, they become everything from general practitioners in small communities to big-firm lawyers, general counsels to civil rights lawyers, policy wonks, and people who put their law licenses to work in government and business endeavors. Affirmative action was helping our classes look more like the communities future lawyers are to serve.

I hope institutions of higher education will find ways to continue to champion diversity. But help in doing that, it’s clear, will no longer come from the courts.

Today, the Court held that Harvard and the University of North Carolina’s admissions programs violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. They ruled that colleges and universities can no longer explicitly use race as a consideration in admissions. Instead, they can, perhaps—until the next legal challenge reaches the Court—try to backdoor those considerations, for instance by permitting students to write admissions application essays about overcoming challenges they’ve faced in their lives.

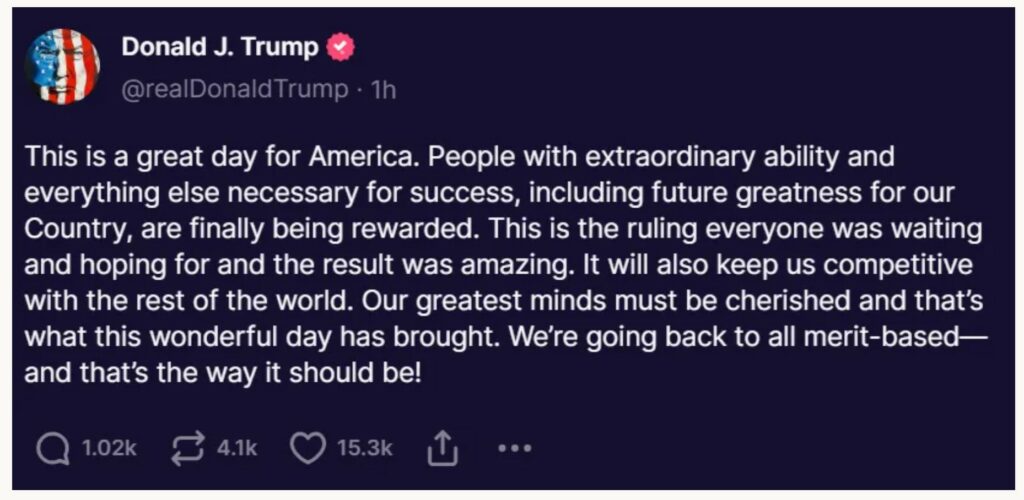

Former President Trump posted on social media about the decisions and made a key point, certainly unintentionally, about today’s decisions. “We’re going back,” he wrote.

Going back is the operative language here. Because these are not decisions based on changing facts or evolving legal rules. It’s yet another override of longstanding precedent, based on the new composition of the Supreme Court. The 6-3 ultraconservative majority continues to implement important pieces of the conservative agenda, without regard for stare decisis. Former Vice President Pence made that clear in comments this morning. He said he was glad to see the conservative majority “we” put in place on the Court end affirmative action.

Today’s decision is about politics, not principle.

The majority opinion was written by Chief Justice Roberts, with concurrences from Justices Thomas, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh.

But it’s Justice Jackson’s dissent that speaks the loudest to anyone who is truly listening. She begins by writing:

“Gulf-sized race-based gaps exist with respect to the health, wealth, and well-being of American citizens. They were created in the distant past, but have indisputably been passed down to the present day through the generations. Every moment these gaps persist is a moment in which this great country falls short of actualizing one of its foundational principles—the ‘self-evident’ truth that all of us are created equal.”

And then, her ringing criticism of the majority:

“Deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life.”

~~~~~~~~

Apparently, her criticism landed with force. Near the end of the Chief Justice Robert’s opinion, he writes,

“A dissenting opinion is generally not the best source of legal advice on how to comply with the majority opinion.”

~~~~~~~~

The context for that comment is important. There has been some suggestion, as people begin to work through the reasoning in more than 200 pages of written opinions in these cases, that there is a workaround for today’s ruling. If there is, it is an exceedingly slender thread.

~~~~~~~~

Chief Justice Roberts concludes;

“nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise. But, despite the dissent’s assertion to the contrary, universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today . . . ‘[W]hat cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly.’”

~~~~~~~~

It is in this context that Justice Roberts admonishes against taking legal advice from Justice Jackson’s dissent. Do not, he warns colleges and universities, try to get around our decision today. The opportunity to use even the process the justices say is permissible—letting applicants raise their individual experiences and qualifications—is clearly constrained. The majority may not have expressly overruled Grutter, but today’s decisions make it all but impossible to consider the legacy of racial discrimination in any meaningful way going forward. (Interestingly, institutions remain free to affirmatively consider privilege, in the form of making legacy college admissions.)

The Court ended affirmative action today, without formally ending it.

Will these decisions have legs beyond education? I hope not. It feels dangerous to even speculate about it. But just as reversing Roe v. Wade seemed like an impossibility until it happened, we live in a time where we must confront the possibilities.

Justice Jackson wrote,

“Our country has never been colorblind. Given the lengthy history of state-sponsored race-based preferences in America, to say that anyone is now victimized if a college considers whether that legacy of discrimination has unequally advantaged its applicants fails to acknowledge the well documented ‘intergenerational transmission of inequality’ that still plagues our citizenry.”

Sixty years after George Wallace stood in the schoolhouse door demanding segregation forever. Chief Justice Roberts would have us believe all is well in America. It’s impossible to miss the echo from his opinion in the voting rights case, Shelby County v. Holder, where he wrote racial discrimination was in the past and protection from it no longer necessary as his justification for gutting the protections of the Voting Rights Act. “Racial disparity in those numbers [low Black voter registration and turnout] was compelling evidence justifying the preclearance remedy and the coverage formula. There is no longer such a disparity.” Roberts is no more accurate today than he was when he wrote that opinion.

President Biden addressed the nation at noon and said that the decision was a severe disappointment to him. It is a strong disappointment to anyone who cares about fairness and equality and the future of our country. The challenge here will be finding a path forward that can turn collective disappointment into action, especially action at the polls, because we will need smart, committed elected representatives to act as a check on and balance to the Court. Wallace may have been forced to step aside in 1963, but we need to make sure we don’t go back.

We’re in this together,

Joyce