Eurostat recently published new data on EU unemployment. The question: how is Southern Europe doing, after the Great Financial Crisis of 2009 when unemployment rates in Spain and Greece were above 20 and even 25%? Compared with the years directly after 2009 Spanish and Greek rates are down a lot, even when levels are still above 10%. But this is not all there is. Next to ‘normal’ unemployment, which is still at a crisis level, economic statisticians also define broad unemployment as ‘people working part-time who want more hours’, ‘people seeking a job but not directly available’, and ‘people available but not seeking’. The reason to define these categories is that people are classified as ’employed’ even when they work 1 hour per week and want to work much more hours. Normal

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Eurostat recently published new data on EU unemployment. The question: how is Southern Europe doing, after the Great Financial Crisis of 2009 when unemployment rates in Spain and Greece were above 20 and even 25%? Compared with the years directly after 2009 Spanish and Greek rates are down a lot, even when levels are still above 10%. But this is not all there is. Next to ‘normal’ unemployment, which is still at a crisis level, economic statisticians also define broad unemployment as ‘people working part-time who want more hours’, ‘people seeking a job but not directly available’, and ‘people available but not seeking’. The reason to define these categories is that people are classified as ’employed’ even when they work 1 hour per week and want to work much more hours. Normal unemployment is a good and sensitive cyclical indicator but because of this only a partial indicator when for measuring total labor slack. In this blog I’ll investigate broad unemployment for the aforementioned countries and France.

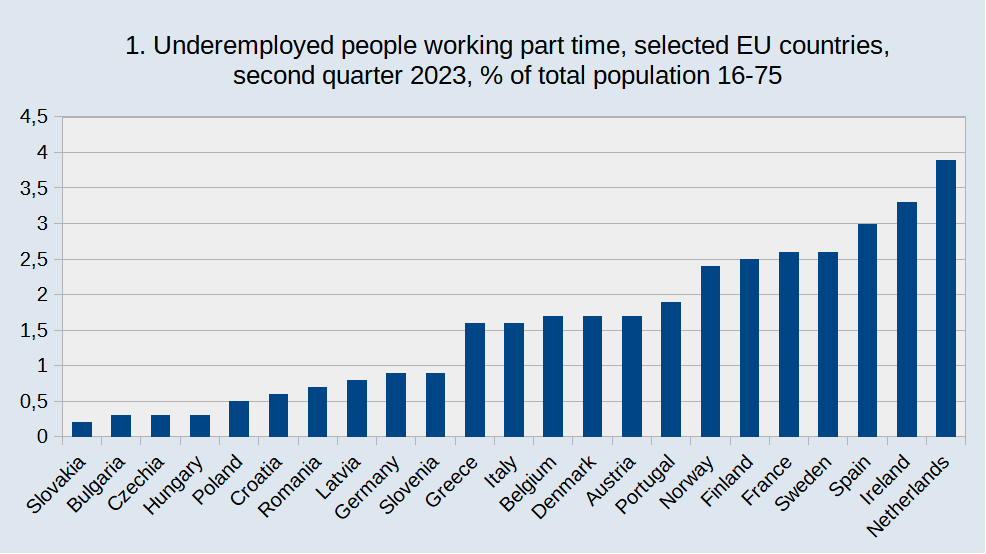

The first question is: does it make a difference. The answer to this is ‘yes’. ‘Normal’ or ‘U3’ unemployment in the Netherlands is one of the lowest in the entire EU and close to the friction level (meaning it can’t go down much more). But the number of people working part-time but wanting more hours is the highest (!) of the entire EU (graph 1). Looking at U3 unemployment only gives an incomplete picture of labor slack in an economy.

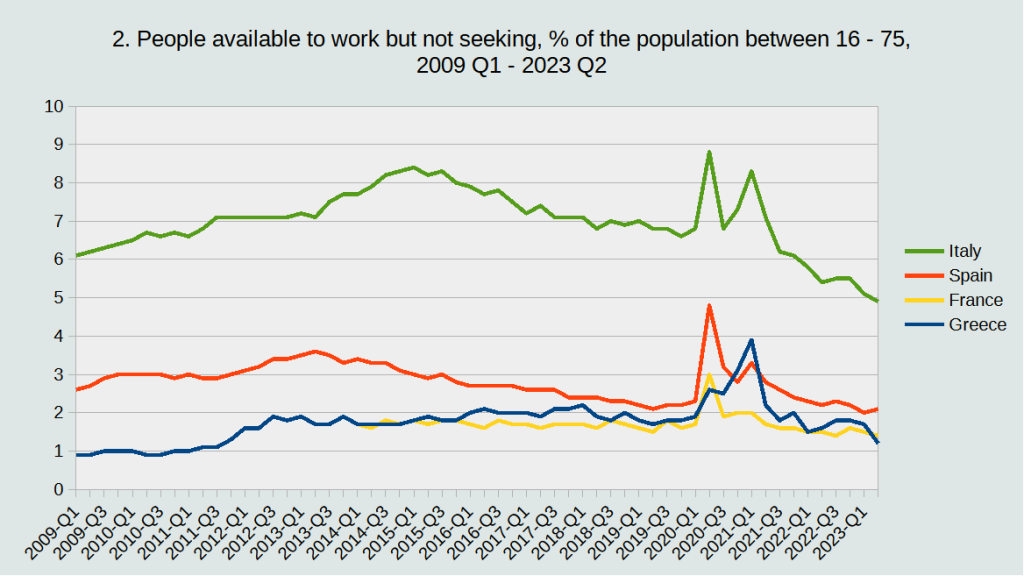

Below, we will look at the longer-term development of this measure of labor slack as well as at the number of people available for a job and not seeking it. This last statistic is sometimes understood as ‘discouraged workers’. This is not wrong, but there might, considering the differences between countries, be large differences between countries when it comes to this, we should ask people why they are not seeking. Taking the data at face value it shows that it is down, compared with 2009, but not with a lot. The most positive remark I can make is that the Italian pace of decline has increased post-COVID, from a snail’s pace to a slug’s pace. Caveat: the French and Greek levels are and were low to begin with, even when the Greek level increased a little at the height of the crisis. The Italian level came down from the 2015 peak but are only marginally lower than in 2009. Bad.

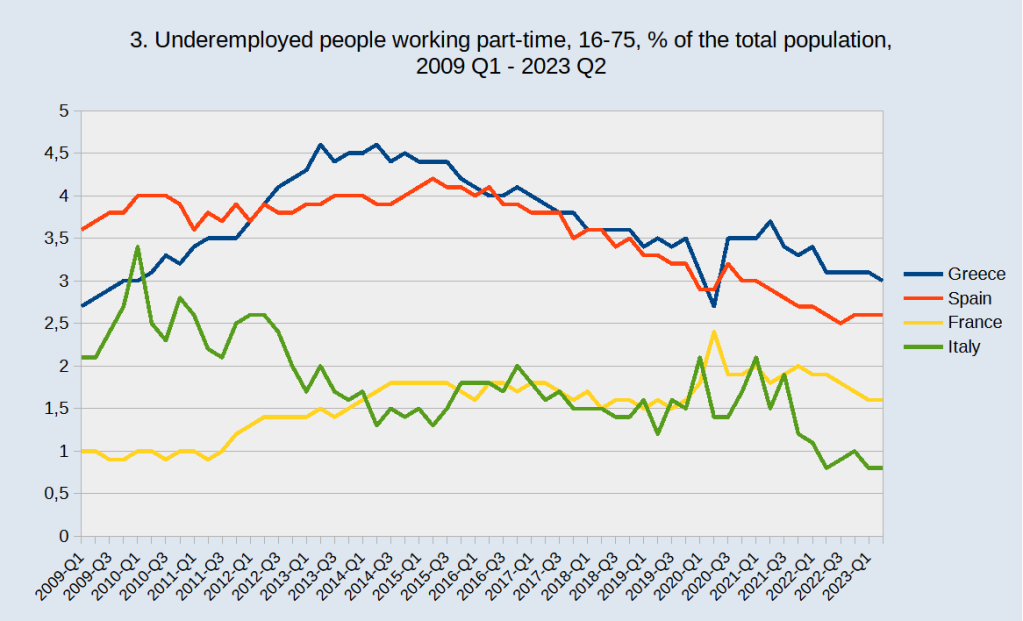

Looking at underemployed part-time workers a mixed picture emerges. In Spain and Greece, it came down after a peak around 2015. In Greece it is, as in France, higher than in 2009. Taken together, Spain and Italy witnessed a development of broad unemployment in line with the decline of U3 unemployment (which, in Italy, was quite limited…). In Greece and France: not so much. Labor slack in Southern Europe is still extremely high.

This means that all talk about inflationary low unemployment or difficulties with the sustainability of public finances and pensions due to an increasing number of elderly are, for the time being and years to come, irrelevant. There is no shortage of labor. Alas.