From David Ruccio We’ve just learned that the corporate payouts—dividends and stock buybacks—of large U.S. firms are expected to hit another record this year. At the same time, John Fernald writes for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco that the “new normal” for U.S. GDP growth has dropped to between 1½ and 1¾ percent, noticeably slower than the typical postwar pace. What’s the connection? Fernald, as is typical of many others who have concluded the United States has entered a period of slow growth, blames the “new normal” on exogenous events like population dynamics and education. The slowdown stems mainly from demographics and educational attainment. As baby boomers retire, employment growth shrinks. And educational attainment of the workforce has plateaued, reducing its contribution to productivity growth through labor quality. The GDP growth forecast assumes that, apart from these effects, the modest productivity growth is relatively “normal”—in line with its pace for most of the period since 1973. What Fernald and the others never mention is that American companies’ embrace of dividends and buybacks comes at the expense of business investment, which is an important contributor to worker productivity and long-term economic growth.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

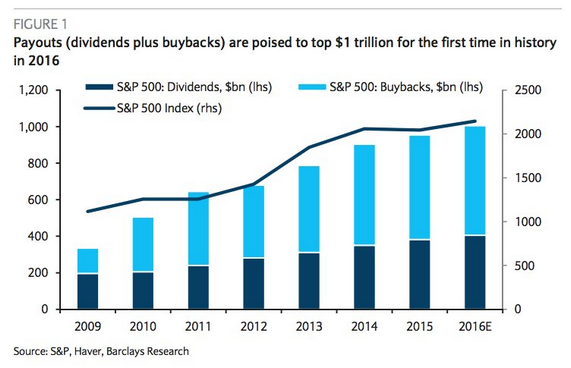

We’ve just learned that the corporate payouts—dividends and stock buybacks—of large U.S. firms are expected to hit another record this year. At the same time, John Fernald writes for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco that the “new normal” for U.S. GDP growth has dropped to between 1½ and 1¾ percent, noticeably slower than the typical postwar pace.

What’s the connection?

Fernald, as is typical of many others who have concluded the United States has entered a period of slow growth, blames the “new normal” on exogenous events like population dynamics and education.

The slowdown stems mainly from demographics and educational attainment. As baby boomers retire, employment growth shrinks. And educational attainment of the workforce has plateaued, reducing its contribution to productivity growth through labor quality. The GDP growth forecast assumes that, apart from these effects, the modest productivity growth is relatively “normal”—in line with its pace for most of the period since 1973.

What Fernald and the others never mention is that American companies’ embrace of dividends and buybacks comes at the expense of business investment, which is an important contributor to worker productivity and long-term economic growth.

In other words, what they overlook is the possibility that the current slowdown—which, “for workers, means slow growth in average wages and living standards”—may be less a product of exogenous events and more the way the U.S. economy is currently organized.

When workers produce but do not appropriate the surplus, they are victims of a social theft. And then, when a larger and larger portion of of the surplus is distributed to shareholders (both outside investors and corporate executives)—that is, the tiny group at the top who share in the booty—workers are, once again, made to pay the cost.