“The Fed Makes a Large Rate Cut and Forecasts More to Come” Jeanna Smialak Writes “The Federal Reserve cut interest rates on Wednesday by half a percentage point, an unusually large move and a clear signal that central bankers think they are winning their war against inflation and are turning their attention to protecting the job market.” I (and Brad DeLong) wonder why the Fed forecasts more rate cuts to come instead of implementing them now? I wonder why is an 0.5% cut considered large? The answer to my faux naivety is that it was not clear until yesterday if the rate would be cut by 0.25% or 0.5%. The fact that it was not cut by more than 5% was not news and not reported. The not naive question of why forecast cuts rather than

Topics:

Robert Waldmann considers the following as important: Federal Reserve, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes Time for Senate Dems to stand up against Trump/Musk

“The Fed Makes a Large Rate Cut and Forecasts More to Come”

Jeanna Smialak Writes

“The Federal Reserve cut interest rates on Wednesday by half a percentage point, an unusually large move and a clear signal that central bankers think they are winning their war against inflation and are turning their attention to protecting the job market.”

I (and Brad DeLong) wonder why the Fed forecasts more rate cuts to come instead of implementing them now? I wonder why is an 0.5% cut considered large? The answer to my faux naivety is that it was not clear until yesterday if the rate would be cut by 0.25% or 0.5%. The fact that it was not cut by more than 5% was not news and not reported.

The not naive question of why forecast cuts rather than implementing them now and possibly reversing them is harder to anser if one does not accept “that’s the way it has always been” as an answer. Brad has noted that an aspect of optimal control is that future shifts are not predictable (this is a feature of optimal control under a broad set of simple assumptions and not a result based on a particular model). The answers have been something about credibility and the expections channel (in other words ‘I don’t know either professor’).

I have two guesses. First it is important that everyone learn of the FED’s move at the same time to avoid insider trading. It is harder to manage this (there is a suspicion that it was not managed last week reported in the free part of Brad’s substack post) “That afternoon, however, Wall Street Journal reporter Nick Timiraos released an article . . . Financial Times reporter Colby Smith followed up . . . and markets perceived that as confirmation that the Fed had engaged in covert communications during the blackout.” Avoiding illegal communication becomes more difficult the more billions early notice is worth. Avoiding the insinuation that this has occurred made by burned bond traders becomes impossible. Another explanation is that the FED just does not want too many billions of gains and losses to follow an announcement.

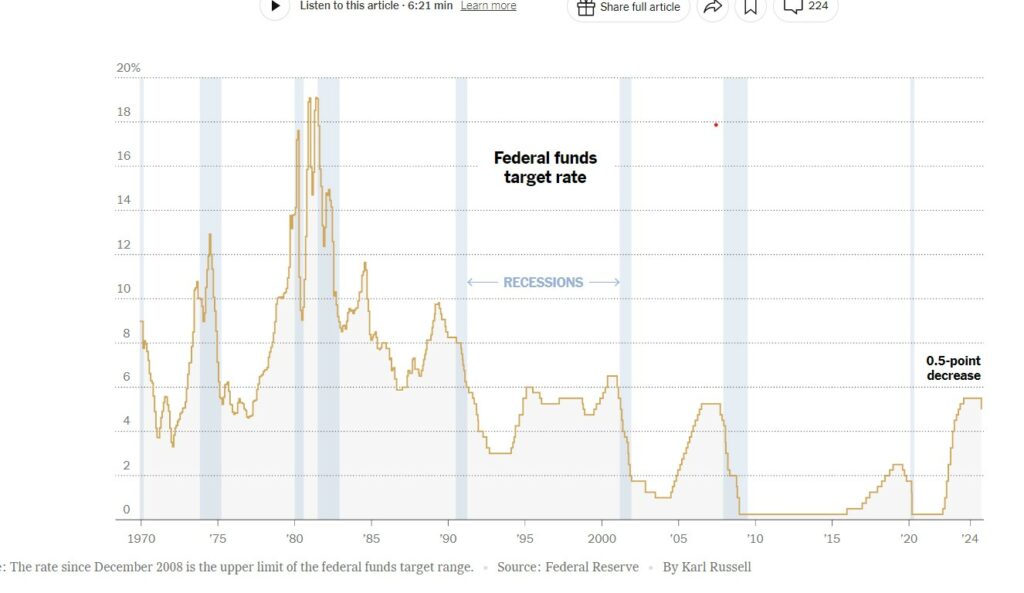

Here is the Federal Funds rate. Note the upward and downward trends, especially the upward trends during 94-5, 99-200, 94-97, 17-19 in response to low unemployment and the fear of future inflations with many very predictable small steps.

I assert that neither concern is related to the dual mandate to seek price stability and full employment. I know there are counterarguments related to credibility and the expectations channel (which I call BS). I think the FED worries about bond traders almost as much as the bond traders worry about the FED. It is certainly wise for bond traders to worry about the FED. I think the attention going the other way is improper.

Now interest rates and future expected interest rates do matter a lot. However their effect is almost exlusively through the mortgage interest rate, demand for houses, relative price of houses, residential investment channel. It is a fact that the partial correlation of interest rates and nonresidential investment is statistically insignificant and invisible even to the attentive pattern seeking eye. This detail has been banished from (almost all) of the academic macroeconomics literature which has advanced by suppressing the distinction between different types of investment.

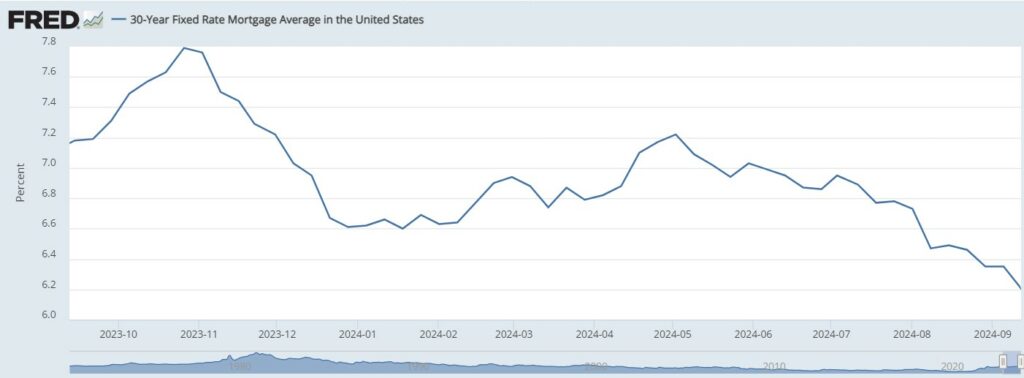

Here is the 30 year fixed mortgage rate series.

It is never so extemely predictable in the short run. It has a clear broken long term trend up and then down down down then what happened in 2022? It responds to the Federal funds rate to an extent which is hard to see but also bizarrely large given the difference in durations and risk premia and everything. I maybe should show treasury bill constant maturity rate series with intermediate durations and tiny risk premia, but I won’t fearing that I might bore you (and being supremely lazy). The series clearly reflects expected future short term rates which reflect future expected inflation both through the automatic demand for bonds fischer effect and the expected future FED anti inflation policy effect.. I am not convinced that such expectations can be managed by the FED. I see no hint of an advantage of many small shifts in the Federal Funds rate versus a few large shifts.

Now look at the past year. I don’t see anything reflecting the many recent shifts in expectations of next months Fed Open Market Committee (FOMC) choices.

I see a downward linear trend starting in May. I think this is the interest rate which affects aggregate demand. I don’t think Powell’s speaches or monthy FOMC decisions affect it much.

Appendix: more usual Robert boring rants

They say “expectations” I ask whose expectations? Again, another advance of modern macro is the choice to model aggregates as choices of a representative agent (modern meaning since about 1980 after 7 years of actual debate). This implies that there is one value of subjective expectations which is the same for all agents. This is a theoretically sound assumption if one makes one of a very few extremely strong assumptions about utility functions or the distribution of income and wealth. One possible assumption is that everyone has identical preferences, income, and wealth. I think one appeal of the representative agent to some of its prominent advocates is that all discussion of income distribution is assumed away. The strong assumptions are easily tested and overwhelmingly rejected by the data. The point (if any) here is that, if one doesn’t assume that everyone is the same, one shouldn’t talk about expected interest rates or inflation or GDP without specifying whose expectations. For the mortgage rates they are the expectations of bankers proposing mortgage rates and potential house buyers deciding whether to buy now or wait. I think this means that those expectations matter for aggregate demand. Neither, not even retail bankers, are like bond traders. The expectations which obsess monetary policy makers and which can be read off from asset prices are quite different from the expectations which affect aggregate demand.

The inflation expectation which affects demand for houses is the expected inrease in the price of houses. This is measured barely at all (as far as I know just a bit for a few cities by Robert Shiller et al). It is extremely important. The few observations show huge shifts, for example from 2005 to 2008. Correlation is not causation, but come on, this clearly made a huge difference.

Other medium term inflation expectations have a big effect on actual inflation. Firms try not to change prices too often and not to change back and forth. This means that current price setting decisions depend on expected medium future price changes by competitors and suppliers. Firms and workers typically set wages for a while (3 years in formal contracts). Future expected inflation matters to them.

Both are strongly relatd to inflation and price stability. Neither clearly related to employement (I explicitly assert this is true for aggregat average wages and aggregate employment in the USA).

The expectations of price setters and wage setters (or wage negotiators and both exist) matter. Are they affected by the FEDs efforts to manage expectations. I (maybe being ignorant) know of no evidence about that and I strongly suspect that the answer is not much.