So, ‘What’s it going to be then, eh’? Will we let migration wreck the EU or will we opt for sound macro policies? The non-far right should double down on the present freedom of movement of people inside the EU. But only when credible macro-economic demand and welfare policies are installed. Otherwise, the internal inconsistencies of the present macro-economic set up will fracture the EU. Which means that the freedom of capital flows, one of the other EU freedoms, might have to be curtailed. Caveat: this post is about migration between EU countries. It is not about refugees or about migration between the EU and the rest of the world. But especially the refugee and external immigration mess (about 5.000 refugees/immigrants have drowned in the Mediterranean in 2016 up till now and hundreds of thousands are ‘apprehended’) will not be sorted until we have post-Brexit clarity about internal migration. Latest news: far right group attacks ‘apprehended’ refugees in Greece. Free movement of people has long been a fact of life in the EU. Think of Think of the proverbial Belgian medic who settles in Benidorm to care for Dutch pensionado’s and Belgian bastards. Or of Dutch horticulturists who are worried about declining immigration of cheap Polish labourers: the Polish economy is picking up.

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

So, ‘What’s it going to be then, eh’? Will we let migration wreck the EU or will we opt for sound macro policies?

The non-far right should double down on the present freedom of movement of people inside the EU. But only when credible macro-economic demand and welfare policies are installed. Otherwise, the internal inconsistencies of the present macro-economic set up will fracture the EU. Which means that the freedom of capital flows, one of the other EU freedoms, might have to be curtailed. Caveat: this post is about migration between EU countries. It is not about refugees or about migration between the EU and the rest of the world. But especially the refugee and external immigration mess (about 5.000 refugees/immigrants have drowned in the Mediterranean in 2016 up till now and hundreds of thousands are ‘apprehended’) will not be sorted until we have post-Brexit clarity about internal migration. Latest news: far right group attacks ‘apprehended’ refugees in Greece.

Free movement of people has long been a fact of life in the EU. Think of Think of the proverbial Belgian medic who settles in Benidorm to care for Dutch pensionado’s and Belgian bastards. Or of Dutch horticulturists who are worried about declining immigration of cheap Polish labourers: the Polish economy is picking up. Surprisingly, hiring Bulgarians or Romanians, who received full access to all other EU countries on 1 January 2014, does not seem to be an alternative to the horticulturists. Anyway, there is no reason that we should necessarily fear the free movement of people. To state a fact so obvious that nobody realizes it: free movement of Belgians and Dutch and Germans across the borders to work or buy or sell never led to serious problems during the last decades.

On the other side – the EU is breaking up because of migration. Which does not come out of the blue. Employment of non-UK EU citizens in the UK has soared even faster than employment of UK citizens during the last years, contrary to employment of non-UK non-EU citizens. And to unprecedented levels. Look here for some data. This is supposed to be one of the reasons for Brexit. But is it? Or is Brexit in fact Euxit and is the EU breaking up because of bad Eurozone macro-economic policies on th level which are praying upon better policies and higher job growth in the UK? That, instead of migration, might be the real existential threat.

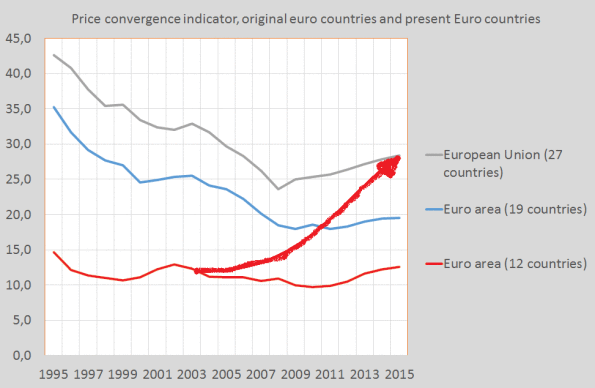

And EU macro policies were bad, before and after 2008. Before 2008, current account imbalances (largely neglected by the Trichet ECB) reached freakish levels in many EU countries. And after 2008 (2007 for some countries) unemployment rates of 15 and even 20%+, unimaginable some years before, became the new abnormal. Such failing policies have, of course, political repercussions. The economists Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick and Christoph Trebesch stated, one year ago now and based upon empirical analysis of 140 years of financial crises and elections (800 elections, 100 crises): “Far-right parties are the biggest beneficiaries of financial crises, while the fractionalisation of parliaments complicates post-crisis governance”. Subsequent developments in the EU proved them right or at least showed that this pattern continues. A pattern which, in the EU, was aggravated by the continuous pushing of the European commission, the IMF and the ECB for wage and pension cuts and restrictions to the rights of labor. It’s not Brexit. It’s Euxit. What to do about this? To answer this question, we have to look at some neglected macro statistics (the graph) and go all the way back to Rome, 1957.

The EU officially knows ‘four freedoms’. One is the free movement of people and workers. The other three are:

- The free movement of goods

- The free movement of capital

- and right of establishment and freedom to provide services

These freedoms are extensions of the article 3 of the 1957 treaty of Rome, which talks of ‘the abolition of obstacles … to the freedom of movement of services, persons and capital’. But the treaty does not state ‘all obstacles’. And the treaty also speaks of the danger of current account imbalances (not: deficits!) and the importance of a social fund to improve employment opportunities for workers. The present, post-2008, European Macro Imbalance procedure, reversing parts of the mistakes of the 1992 treaty of Maastricht, has belatedly brought the importance of current account imbalances to the fore again. The main reason these imbalances came to the fore again was simple: rogue capital flows. Unhampered flows of capital enabled and contributed to extreme booms in countries like Spain, the Baltics and a whole score of other countries. The treaty of Rome acknowledged the importance of preventing current account imbalances – but, written in a time of full employment, clearly underestimated the power of unhampered flows of capital and their reversals.

At the same time, the EU has been enlarged. Which caused an increase in the dispersion of prices levels (graph). When we look at stable groups of countries we see a decline of this dispersion until 2008 and a more or less stable level afterwards. But groups were not stable. Many new countries with price levels which were often only about half of the western European level and which themselves are clear testimony of the failed process of transition in Eastern Europe entered the EU and the Eurozone. While the abolition of ever more obstacles to the free flow of people and capital caused increasing tensions, showing up in imbalances and, when free flows of capital suddenly reversed, Über-unemployment. Which of course led to high migration and low-wage competition. Mind that one Euro remitted from Ireland to Bulgaria triples its purchasing power, which means that migrant labor (including the hundreds of thousands of Eastern European truck drivers driving through Germany, France and other countries) can afford to earn a lot less than their western European compatriots. And does anybody has a tally of Eastern European prostitutes working in the brothels of Amsterdam, London, Paris and Frankfurt? Ehhh… no. But even the tip of the iceberg is pretty large. The good news is of course that, as the Polish example shows, migration is mainly about jobs and not so much about nominal wage differences. Which means that contra-cyclical macro policies aimed at employment will not just stabilize the EU and the Euro economy but also entire countries. Let’s start with a 70+ EU pension of 200,– a month (which, in Bulgaria, has three times the purchasing power as in Luxembourg), financed by a Land tax which as such already mitigates capital flows as well as by a Tobin tax on speculative financial transactions. Such policies, instead of walls, might save the EU.

Summarizing: don’t be afraid of working people. Be afraid of bad policies.