From David Ruccio President-elect Donald Trump has inherited an economy that is as divided as the electorate. The question is, what will that economy look like if and when Trump’s right-wing national-populist promises and post-election proposals are enacted? As I have shown in the three installments of the first part of this series, “Class Before Trumponomics” (here, here, and here), over the course of recent decades and continuing through the crash and recovery, the class nature of the U.S. economy was transformed in dramatic fashion. Capital was able to pump more surplus out of U.S. workers and, through the combined processes of financialization, globalization, and concentration, to capture more of the surplus from workers both at home and around the world. Labor, too, was radically transformed—and weakened by many forces, including automation, declining unionization, ethnic and racial disparities, immigration, and a low minimum wage. Overall, underlying the grotesque levels of inequality that characterize the United States have been the opposing forces of an increasing capital share and a declining labor share. That’s what the U.S. economy looks like as Trump celebrates his victory and, along with his Cabinet, economic team, and a new Republican Congress, develops a set of economic plans to “make America great again.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

President-elect Donald Trump has inherited an economy that is as divided as the electorate. The question is, what will that economy look like if and when Trump’s right-wing national-populist promises and post-election proposals are enacted?

As I have shown in the three installments of the first part of this series, “Class Before Trumponomics” (here, here, and here), over the course of recent decades and continuing through the crash and recovery, the class nature of the U.S. economy was transformed in dramatic fashion. Capital was able to pump more surplus out of U.S. workers and, through the combined processes of financialization, globalization, and concentration, to capture more of the surplus from workers both at home and around the world. Labor, too, was radically transformed—and weakened by many forces, including automation, declining unionization, ethnic and racial disparities, immigration, and a low minimum wage. Overall, underlying the grotesque levels of inequality that characterize the United States have been the opposing forces of an increasing capital share and a declining labor share.

That’s what the U.S. economy looks like as Trump celebrates his victory and, along with his Cabinet, economic team, and a new Republican Congress, develops a set of economic plans to “make America great again.”

What will things look like moving forward? There is, of course, a high degree of uncertainty concerning the changes we can expect from the Trump administration’s proposals. For a variety of reasons, we don’t know what those proposals will be—not only because Trump put forward different versions of his “promises” (and, in some cases, like saving the Carrier plant jobs, he didn’t even remember he’d made such a promise on the campaign trail), but also because his Cabinet members and the Republican Congress have their own ideas of what they’d like to do. Plus, unexpected developments in the United States and around the world will surely require changes to whatever proposals are formulated or implemented.

All we can do, then, is analyze the potential effects of proposals that have been announced—on the assumption they will be at least general guides to the policies the Trump administration and their allies attempt to enact.

I don’t pretend here to be able to analyze the effects of all of the economic proposals associated with Trump, his Cabinet and economic team, and the new Congress, which run from repealing the Affordable Care Act to renegotiating international trade agreements. Instead, I want to focus on three that were prominent during the campaign and, by virtue of their size, have the potential of dramatically altering the current class landscape: tax cuts, reducing regulations on business, and deporting undocumented immigrants.

While the details remain to be worked out, the centerpiece of Trump’s economic strategy—as he explained in speeches in Detroit and New York—is a plan to cut taxes on both individuals and corporations. While others have focused on whether the plan’s numbers are consistent (they aren’t, according to Greg Ip for the Wall Street Journal) and its effects on the national debt (the Tax Policy Center argues it could increase the debt by nearly 80 percent of GDP by 2036), I want to concentrate here on the class implications of the tax plan.

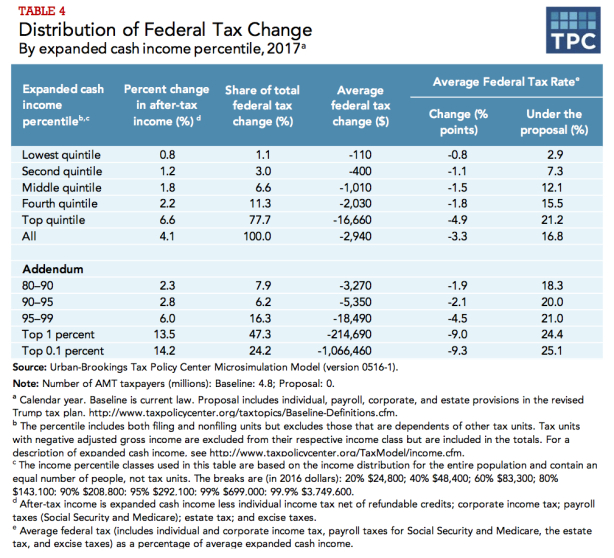

It should come as no surprise that, based on the analysis by the Tax Policy Center, the highest-income households would receive the largest benefits from the proposed individual income-tax cuts, both in dollars and as a percentage of income.

The top quintile—or fifth of the distribution—would receive an average tax cut of $16,660 (a 6.6 percent increase in after-tax income), the top 1 percent an average tax cut nearly 13 times larger ($214,690, or 13.5 percent of after-tax income), and the top 0.1 percent an average tax cut approaching $1.1 million (14.2 percent of after-tax income). In contrast, the average tax cut for the lowest-income households would be $110, 0.8 percent of after-tax income. Middle-income households would receive an average tax cut of $1,010, or 1.8 percent of after-tax income.

Given the fact that the income of taxpayers at the top comes mostly from distributions of the surplus (in the form of executive salaries, interest, dividends, and so on), the Trump tax plan implies they will be able to keep more of the surplus they have managed to capture and to decide individually what to do with their share of the surplus—to spend it on conspicuous consumption or utilize it to acquire even more private wealth.

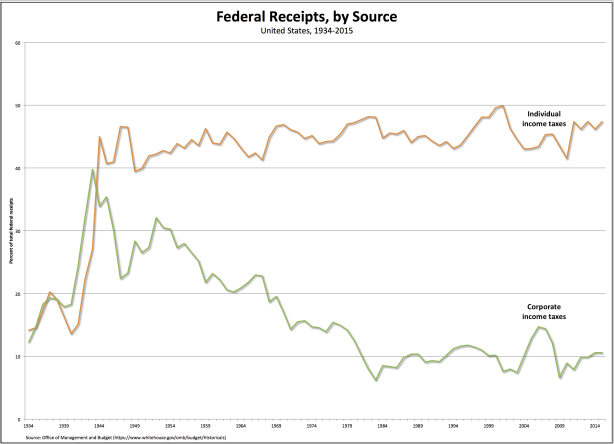

Trump also proposes to cut the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 15 percent. But because the effective corporate tax rate (16.1 percent in 2012, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office [pdf]) is much lower than the statutory rate, if corporations were required to pay the proposed lower statutory rate, the status quo would be largely unchanged. In other words, U.S. corporations would pay no more than they currently do in the form of taxes (and possibly less, if the future effective rate falls below the lower statutory rate), and the contribution of corporate income taxes to total federal revenues (only 10.6 percent in 2015) would continue to be low by historical standards (23 percent as recently as 1966).

It is impossible to predict what corporations will do with the share of the surplus that is not subject to federal taxation. However, if the current pattern holds, we can expect a continuation—and perhaps even an acceleration—of mergers and acquisitions, stock buybacks, and job-displacing investment in robotics and other forms of automation that will boost the profits, especially of large corporations.

As I see it, the result of proposed cuts in both individual and corporate taxes is that more of the surplus would be captured and kept in private hands and consequently less will be available—via taxes—for social spending. And the only way to prevent fiscal deficits and federal debt from increasing (as Republicans have ling claimed is one of their goals) will be to cut spending on federal programs, which will be felt mostly by workers and their families.

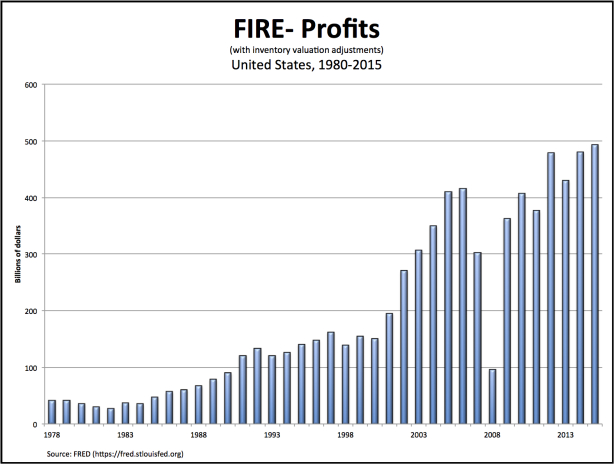

Throughout the presidential campaign, Trump also promised “to cut regulations massively”—and according to Stephen Mnuchin, Trump’s Treasury Secretary designee, revising Dodd-Frank is “the number one priority on the regulatory side.” Here there is no clear proposal but it’s likely four features of Dodd-Frank will come under scrutiny and perhaps be undone or seriously revised: capital controls (the rule stating that the eight largest banks in the country should maintain an additional layer of capital to protect against losses), “enhanced supervision” (which requires the Federal Reserve to evaluate banks with assets of at least $50 billion more closely than those with fewer assets), the so-called Volcker Rule (which prohibits banks from proprietary trading and restricts investment in hedge funds and private equity by commercial banks and their affiliates), and the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (which regulates the offering and provision of consumer financial products and services under federal consumer financial laws).

Between the TARP bailout and Dodd-Frank legislation, the amount of the surplus captured by the financial sector has recovered—and is larger now ($493.3 billion) than it was before the crash ($415.1 in 2006). It’s likely, if the Trump administration succeeds in revising or repealing key provisions of the new legislation, financial activities will continue to expand and the share of the surplus they manage to siphon off from other sectors—in the United States and around the world—will also continue to grow.

Finally, Trump promised to “prioritize the jobs, wages and security of the American people” by establishing new immigration controls, with a series of measures outlined in his 10-point plan. A great deal depends on whether or not the administration is able to fund the activities required by the plan, such as deporting the estimated 11.1 million immigrants living without documents in the United States (which would require large increases in funding from Congress to increase the current workforce of immigration agents and judges to be able to lawfully handle that many deportations—not to mention the logistical challenge of locating so many immigrants, many in the country for years with deep family and community ties). In my view, what is more likely is that there will be a great deal of talk about curbing immigration (with some selective high-profile anti-immigrant actions), which will serve to increase the level of fear within immigrant communities and make existing undocumented workers even less likely to seek assistance from private agencies and public departments.

The obvious beneficiary of such a public campaign against undocumented workers will be their employers—especially in such industries as farming, maintenance, construction, and food (according to the Pew Research Center). They will continue to be able to hire undocumented farmhands, maids, groundskeepers, laborers, and cooks at wages that are less than those paid to legal immigrants and native-born workers—in addition to subjecting them to more violations of labor laws (including minimum wages, overtime pay, and so on).* And because undocumented workers will be driven even further underground, with fewer viable alternatives, the position of both legal immigrants and low-wage workers who are also employed in those industries will likely be weakened, thus increasing the profits of corporations that hire anyone from the three groups of workers.

While we need to be cautious in terms of an analysis of the effects of the Trump administration’s promises and proposals, for reasons I explain above, it is likely we are going to see an accelerated or supercharged version—instead of a softening, much less a reversal—of the class dynamics of the U.S. economy in recent years and decades. There’s a good chance corporations that appropriate the surplus from workers, as well as wealthy individuals who manage to capture a portion of that surplus, will be able to get and keep even more of the surplus—and they will continue to be able to make their own private decisions about what to do with it. For its part, the financial sector will probably continue to grow in importance, with even fewer limits or safeguards, thus channeling more of the surplus into the profits of banks and insurance companies and the salaries of their highest-paid employees. And a campaign against undocumented workers will undoubtedly make their situation—and that of other low-wage workers, both immigrant and native-born—much weaker vis-à-vis their employers.

Therefore, I expect the class transformations that have come to characterize the U.S. economy, between and within labor and capital, will likely continue in an even more intense fashion under the aegis of the new administration. The only real change I envision, at least at this early date, is Trump’s willingness to target specific groups and entities according to a right-wing populist sense of the “national interest,” which may serve to deflect attention from the inequalities and injustices inherent within the existing set of economic institutions.

Alternatively, Trump’s actions may end up mocking the arrogance and ignorance of the existing elites—and thus, however ironically, unmasking those class inequalities and injustices.

*According to a landmark 2009 survey of thousands of workers, by Annette Bernhardt et al. (pdf), 37 percent of unauthorized immigrant workers were the victims of minimum wage-law violations at the hands of their employers (meaning they were not paid the legally required minimum wage). And an astonishing 84 percent of unauthorized immigrant workers who worked full-time were not paid for overtime, that is, they were not paid the legally required time-and-a-half rate for the hours they worked in a week beyond 40 hours.