From David Ruccio When it comes to artificial intelligence and automation, the current White House seems to want to have it both ways. On one hand, it warns about the potentially unequalizing, “winner-take-most” effects of the economic use of artificial intelligence: Research consistently finds that the jobs that are threatened by automation are highly concentrated among lower-paid, lower-skilled, and less-educated workers. This means that automation will continue to put downward pressure on demand for this group, putting downward pressure on wages and upward pressure on inequality. In the longer-run, there may be different or larger effects. One possibility is superstar-biased technological change, where the benefits of technology accrue to an even smaller portion of society than just highly-skilled workers. The winner-take-most nature of information technology markets means that only a few may come to dominate markets. If labor productivity increases do not translate into wage increases, then the large economic gains brought about by AI could accrue to a select few. Instead of broadly shared prosperity for workers and consumers, this might push towards reduced competition and increased wealth inequality.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

When it comes to artificial intelligence and automation, the current White House seems to want to have it both ways.

On one hand, it warns about the potentially unequalizing, “winner-take-most” effects of the economic use of artificial intelligence:

Research consistently finds that the jobs that are threatened by automation are highly concentrated among lower-paid, lower-skilled, and less-educated workers. This means that automation will continue to put downward pressure on demand for this group, putting downward pressure on wages and upward pressure on inequality. In the longer-run, there may be different or larger effects. One possibility is superstar-biased technological change, where the benefits of technology accrue to an even smaller portion of society than just highly-skilled workers. The winner-take-most nature of information technology markets means that only a few may come to dominate markets. If labor productivity increases do not translate into wage increases, then the large economic gains brought about by AI could accrue to a select few. Instead of broadly shared prosperity for workers and consumers, this might push towards reduced competition and increased wealth inequality.

But then it invokes, and repeats numerous times across the report, the usual mainstream economists’ nostrums about the “strong relationship between productivity and wages”—such that “with more AI the most plausible outcome will be a combination of higher wages and more opportunities for leisure for a wide range of workers.”

Except, of course, historically that has not been the case—certainly not in the United States.

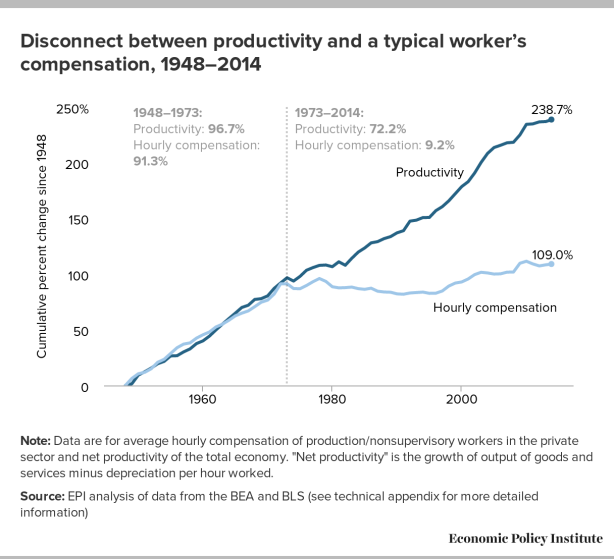

For example, from the early 1970s to the present, workers’ wages have not kept pace with increases in productivity. Not by a long shot. As is clear from the chart above, productivity since 1973 has risen much more than workers’ compensation—72.2 percent, compared to a paltry 9.2 percent.

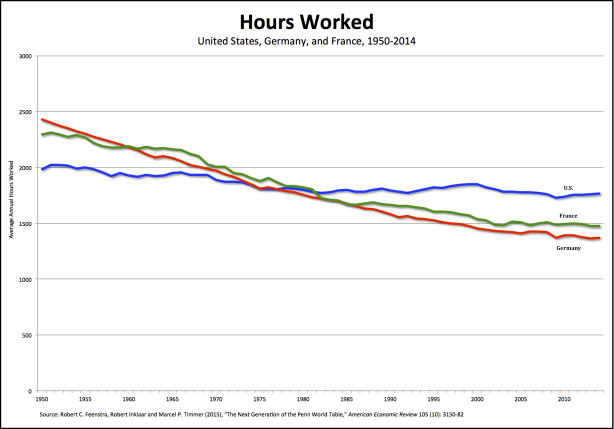

And while over the same period hours worked have in fact fallen, the decrease in the United States (a minuscule 5.6 percent) has been far less than the increase in productivity—and much less than in other countries, such as France (24 percent) and Germany (27.3 percent).

So, yes, whether the use of artificial intelligence leads to improvements for U.S. workers—in the form of higher wages and fewer hours worked—”depends not only on the technology itself but also on the institutions and policies that are in place.”

But the experience of the past four decades suggests it will not benefit the American working-class.

And there’s nothing to suggest that trend won’t continue—unless, of course, there is a radical change in economic institutions and policies, which allow workers to have much more of a say in the technologies that are adopted and how wages and hours are set.