Predictably (as energy prices can’t fall forever) consumer price inflation in the EU recently increased. The present level is 1,1% which is, in a historical perspective, outright low. Also, ‘core’ inflation (which, unlike consumer price inflation, has never been negative) remained subdued and even below 1%. Predictably, however, people already start to scream that inflation is soaring and we should be afraid about worthless money. They are wrong. Four reasons: Inflation does not measure the purchasing power of money. It measures the purchasing power of nominal income. A nice example of this: the introduction of the euro. Despite the introduction of an entirely new kind of money and a whole new set of prices, the purchasing power of the income of households stayed more or less the same. As such, consumer price inflation shows what a household could have bought when nominal income had stayed the same and purchasing patterns had stayed the same. This is an extremely useful metric. But real households are of course smart. It’s not only the price level which changes, but relative prices change, too. When nominal income stays the same and prices increase (or even when nominal income increases) they will change their pattern of consumption.

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Predictably (as energy prices can’t fall forever) consumer price inflation in the EU recently increased. The present level is 1,1% which is, in a historical perspective, outright low. Also, ‘core’ inflation (which, unlike consumer price inflation, has never been negative) remained subdued and even below 1%. Predictably, however, people already start to scream that inflation is soaring and we should be afraid about worthless money.

They are wrong. Four reasons:

- Inflation does not measure the purchasing power of money. It measures the purchasing power of nominal income. A nice example of this: the introduction of the euro. Despite the introduction of an entirely new kind of money and a whole new set of prices, the purchasing power of the income of households stayed more or less the same. As such, consumer price inflation shows what a household could have bought when nominal income had stayed the same and purchasing patterns had stayed the same. This is an extremely useful metric. But real households are of course smart. It’s not only the price level which changes, but relative prices change, too. When nominal income stays the same and prices increase (or even when nominal income increases) they will change their pattern of consumption. Economists should pay much more attention to such shifts, though they should of course take note that some of the most important prices of our economy (the mortgage interest rate!) are not included in the consumer price index. These changes in relative prices and spending patterns indicate that the idea of ‘the purchasing power of money’ is bonkers. The introduction of new products underscores this. What households do, want to do and can do with money changes all the time. This even leaves out ‘consumer credit’. Whenever it becomes easier or more difficult to obtain consumer credit, this changes the purchasing power of households.

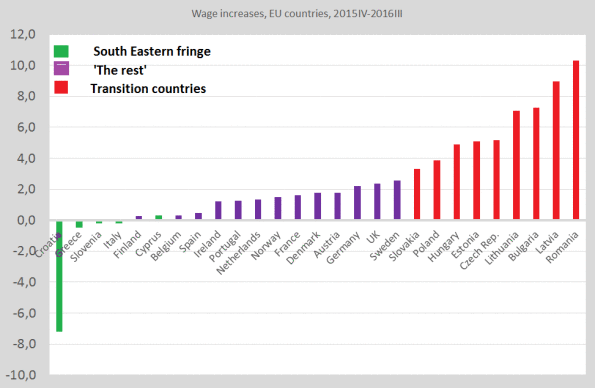

- We should not be afraid about the debasement of money but about the debasement of nominal income: wages. And ‘mixed income’ of the self-employed. Nominal income should increase as much – and preferably a little more – than consumer price inflation. In 2016 this happened (at least when it comes to wages) but this was largely due to lower energy prices. At this moment, wage increases in many European countries are low, which, as energy prices are on the rise again, means that we run the risk of a deflationary downdraft (interestingly, wage increases in many transition countries are considerable which, as long as they keep asset price bubbles in check, is a good thing).

- It’s not just about consumer prices. A large chunk of household consumption is provided by the government: education, justice, coastal defences and the like. This is not measured by the consumer price index. After 2008, prices rises of these services were (as long as they were not ‘kind-of-privatized’) very mitigated, to a large extent because increases (if any) of government wages were lower than average. The price increases of government products and services used by households have often been even lower than the increases of consumer prices.

- Low increases of wages of course also means that ‘cost push inflation’ will be subdued. At this moment we do seem to have some kind of wage-price spiral in some countries – but one which goes down.