From David Ruccio In discussing the textbook treatment of the minimum wage, James Kwak provides a perfect example of how contemporary mainstream economics “can be more misleading than it is helpful.” Kwak refers to the problem as “economism.”* For me, borrowing from a different tradition, it is a case of “vulgar economics.” The argument against increasing the minimum wage often relies on what I call “economism”—the misleading application of basic lessons from Economics 101 to real-world problems, creating the illusion of consensus and reducing a complex topic to a simple, open-and-shut case. According to economism, a pair of supply and demand curves proves that a minimum wage increases unemployment and hurts exactly the low-wage workers it is supposed to help. The argument goes like this: Low-skilled labor is bought and sold in a market, just like any good or service, and its price should be set by supply and demand. A minimum wage, however, upsets this happy equilibrium because it sets a price floor in the market for labor. If it is below the natural wage rate, then nothing changes. But if the minimum (say, .25 an hour) is above the natural wage (say, per hour), it distorts the market. More people want jobs at .25 than at , but companies want to hire fewer employees. The result: more unemployment.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

In discussing the textbook treatment of the minimum wage, James Kwak provides a perfect example of how contemporary mainstream economics “can be more misleading than it is helpful.”

Kwak refers to the problem as “economism.”* For me, borrowing from a different tradition, it is a case of “vulgar economics.”

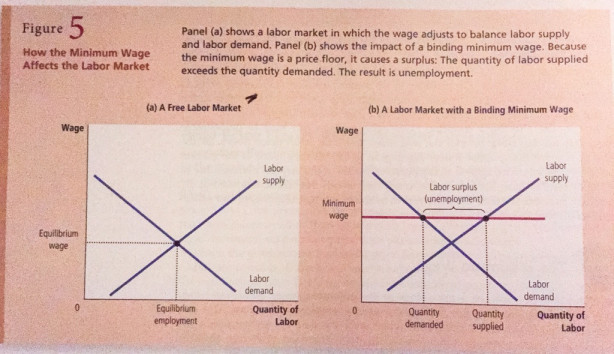

The argument against increasing the minimum wage often relies on what I call “economism”—the misleading application of basic lessons from Economics 101 to real-world problems, creating the illusion of consensus and reducing a complex topic to a simple, open-and-shut case. According to economism, a pair of supply and demand curves proves that a minimum wage increases unemployment and hurts exactly the low-wage workers it is supposed to help. The argument goes like this: Low-skilled labor is bought and sold in a market, just like any good or service, and its price should be set by supply and demand. A minimum wage, however, upsets this happy equilibrium because it sets a price floor in the market for labor. If it is below the natural wage rate, then nothing changes. But if the minimum (say, $7.25 an hour) is above the natural wage (say, $6 per hour), it distorts the market. More people want jobs at $7.25 than at $6, but companies want to hire fewer employees. The result: more unemployment. The people who are still employed are better off, because they are being paid more for the same work; their gain is exactly balanced by their employers’ loss. But society as a whole is worse off, as transactions that would have benefited both buyers and suppliers of labor will not occur because of the minimum wage. These are jobs that someone would have been willing to do for less than $6 per hour and for which some company would have been willing to pay more than $6 per hour. Now those jobs are gone, as well as the goods and services that they would have produced.

That’s exactly the argument presented by Harvard’s Gregory Mankiw in his best-selling textbook Principles of Microeconomics. He uses neoclassical economic theory to distinguish (as in the figure above) a “free labor market,” where the market is in equilibrium and there is full employment, and a “labor market with a binding minimum wage,” where there is a surplus of labor or unemployment. In the latter, at a minimum wage above the equilibrium wage, the quantity demanded of labor (by employers) is less than the quantity supplied of labor (by workers). Thus, in his view,

the minimum wage raises the incomes of those workers who have jobs, but it lowers the incomes of workers who cannot find jobs.

Mankiw then supplements his discussion of the negative effects of the minimum wage by asserting it “has it greatest impact on the market for teenage labor.” Low wages, he argues, are appropriate for such workers because they “are among the least skilled and least experienced members of the labor force.”**

Only after presenting the model of unemployment created by a minimum wage and focusing on teenage workers does Mankiw admit that the minimum wage “is a frequent topic of debate” among economists, who “are about evenly divided on the issue.”***

Nowhere does Mankiw discuss the history of the minimum wage nor the determinants of either the supply of or demand for workers who are forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work for a wage at or below the minimum wage. He is thus content, like many nineteenth-century economists, to “interpret, systematise and defend in doctrinaire fashion the conceptions of the agents of bourgeois production who are entrapped in bourgeois production relations.”

That is the very definition, in our own time, of vulgar economics.

*I hesitate to use Kwak’s term economism because, in my view, it signifies something different: the reduction of all social phenomena, in the first or last instance, to the economy (or some part thereof, such as the relations or forces of production). In other words, economism is an economic determinism—the positing of some kind of economic essence. The irony, of course, is that neoclassical economics represents an essentialism but of a different sort: it reduces all economic and social phenomena to a given human nature. Neoclassical economics is therefore a theoretical humanism.

**Later, he adds that such teenagers are “from middle-class homes working at part-time jobs for extra spending money.” Even less reason, then, to worry about such low-wage workers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, minimum-wage workers do tend to be young. But they’re not just teenagers. In 2015, more than 2.5 million workers in the United States received wages at or below the federal minimum wage (3.3 percent of the labor force), of whom 1.4 million were 25 years or older (2.2 percent of the labor force).

***The 2006 survey Mankiw refers to was conducted only among members of the American Economic Association, the main organization of mainstream economists in the United States. It is interesting that the minimum wage is one of the few issues on which there was no consensus, even among mainstream economists. About 38 percent wanted it increased, while 47 percent wanted it eliminated entirely.